How Pharma Lost Its Edge in Washington

Major drug company CEOs are about to appear before Congress to address drug pricing—for the first time ever.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For decades drug manufacturers in the U.S. have been able to set prices virtually at will. They introduce new pharmaceuticals with five- or even six-figure price tags, while they raise the prices of existing drugs as much as 10 percent a year. Unlike their counterparts in the airline or auto industries, most leaders of these companies have never appeared before Congress. Until now.

The heads of pharma giants Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi, among others, will face members of the Senate Finance Committee on Feb. 26, the opening move in what promises to be a long chess match between the prescription drug industry and Congress over how to rein in prices.

For years lobbyists from PhRMA, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, have kept Congress at bay. They’ve defeated bills that would have curbed anticompetitive practices and allowed the importation of cheaper drugs, and managed to avoid negotiating with the federal government over prices for Medicare recipients during the Affordable Care Act debate. PhRMA faced opposition from natural rivals including generic drug makers, but not often from patient groups, which tend to be funded by the brand-name drug companies competing to treat their conditions. This time the industry is up against what PhRMA President Steve Ubl calls a “well-organized, well-financed” price-fighting coalition, made up of “organizations and others that wake up every day with the ambition of keeping drug pricing as high on the political radar screen as possible.”

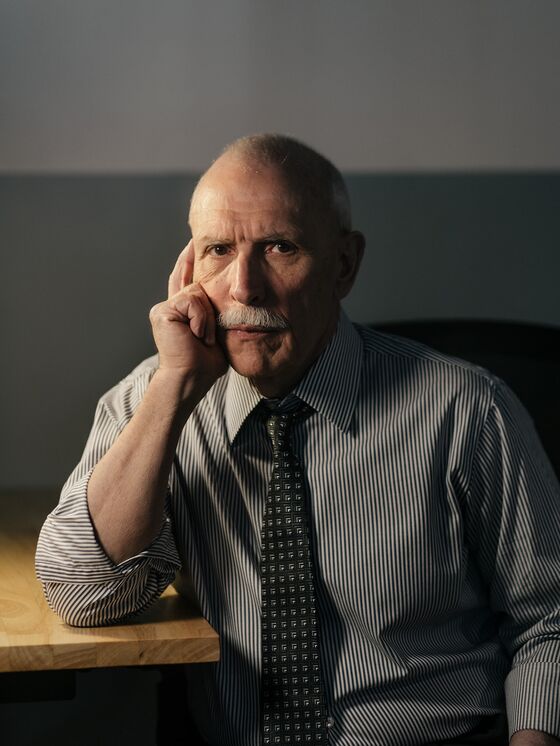

The most high-profile of these is Patients for Affordable Drugs, founded by David Mitchell, who started the communications firm GMMB and helped lead public-awareness efforts including “Save Darfur” and “Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids.” He was also diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2010. At the time he decided to retire in 2016, the list prices of the two cancer drugs he was taking totaled $440,000 for a year of treatments; knowing that most patient advocacy groups relied on drug companies for funding, he decided to start one that didn’t.

“We stepped into a void,” he says. His opposition was well-armed. Last year, PhRMA spent about $28 million on lobbying, according to the Center for Responsive Politics; Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), a lobbying group for the biotech industry, spent $9.9 million, while individual companies spent comparable amounts, including $11.4 million for Pfizer Inc. and $6.8 million each for Merck and Eli Lilly. Mitchell managed to raise more than $10 million in 2018, all from Arnold Ventures, started by Enron trader-turned-hedge fund manager John Arnold and his wife, Laura, a former oil executive. Drug pricing is an example of a “real market failure” resulting from “inefficiencies or outside influence,” says Arnold Ventures spokeswoman Vanessa Astros.

“No one person and no one organization on an issue like this changes anything,” Mitchell says. Luckily, he has partners, including the Campaign for Sustainable Rx Pricing, which spun off of the National Coalition on Health Care last year. The Campaign is backed by more than 30 players in the health-care system, including drug purchasing group Vizient, insurers Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, CVS Health, and the health-insurance industry lobby group. “Change happens because a lot of people go to work,” Mitchell says. “All we think we’re doing is adding a piece that is missing.”

The first sign the drug lobby was losing its grip on Congress came in February of last year, when PhRMA was blindsided by a change lawmakers made to Medicare, putting drugmakers on the hook for more of seniors’ prescription costs. As a result, the companies had to offer a much more generous discount to beneficiaries who fall into the so-called doughnut hole coverage gap, marking down retail costs by 70 percent instead of the previous 50 percent. PhRMA spent the summer lobbying to reduce the size of the discount, but by the time the congressional session ended in December, it hadn’t succeeded.

Drug prices are one of the few areas where the Trump White House and Democrats in Congress may work together. The administration is proposing an “international pricing index” that would peg prices to those paid by nationalized health services, which have used their market power to keep prices consistently lower than in the U.S. This won’t be an easy one for the drug lobby to fight with a unified voice. Preventing price controls is in the interest of the entire industry, but once the conversation becomes not whether but how to control drug prices, drugmakers’ competing interests take hold. They can’t avoid the conversation anymore, says Rob Smith, an analyst at Capital Alpha Partners in Washington. “They realize they have to put something on the table.”

James Greenwood, president of BIO, who says he spends 95 percent of his time talking about drug prices, thinks politicians are missing the point. “People are not angry at the price of drugs, they’re angry at what they pay,” he says. This has long been Big Pharma’s refrain: Patients should direct their anger toward high-deductible insurance plans that force them to shoulder an ever-growing portion of their drug costs. Drug companies also point to the fees charged by middlemen, who negotiate preferred status for them in certain health plans, as a reason for drugs’ higher list prices.

Greenwood says it’s possible the industry would float inflation caps to limit price hikes, and PhRMA’s Ubl says he’s working on alternatives to the international pricing proposal. Ubl adds that his group wants to be “constructive,” but it appears to be relying on its old playbook so far. “Our desire is for patients to have lower out-of-pocket costs” set by insurers, said Lori Reilly, PhRMA’s executive vice president for policy, research, and membership, when asked at a January roundtable whether the group had specific alternatives to propose to the administration’s international pricing policy draft.

Alex Azar, Trump’s secretary of Health and Human Services, has made it clear that he and the president want lower costs for patients across the board, but that any solution must include lower drug prices. “You have a Congress that is committed to drug pricing reforms,” says Smith, the analyst. “You have a president that has made no bones about his disdain for pharma and their pricing practices.” And you have Azar, who was once a president of drugmaker Eli Lilly & Co.’s U.S. affiliate, but “knows that his job performance is being measured based on his ability to make some of these changes Trump wants.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.