When a $2.1 Million Drug Could Cure Your Child’s Fatal Disease

When a $2.1 Million Drug Could Cure Your Child’s Fatal Disease

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Gene therapy is bringing out the best in America’s health-care system—and its worst. Zolgensma, the first systemic gene therapy of its kind that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved, appears to cure in one shot a rare muscle-destroying disease that can be a death sentence for infants and toddlers. (The kids still carry the gene mutation; they just don’t exhibit the eventually fatal symptoms.) It’s also the world’s most expensive medication. Novartis AG set the price at $2.1 million after the FDA approval came down on May 24, and some families have been left scrambling for ways to get the drug in its first several months on the market.

The medical system always faces a learning curve with a new treatment, particularly one this revolutionary, but the stakes for patients who could benefit from Zolgensma have made things that much tougher. Only 400 American babies a year are born with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), but left untreated, it kills them before they turn 2 years old.

“It’s a challenge anytime you introduce a new therapy into the marketplace, to gain understanding from the insurers,” says Dave Lennon, president of the Novartis division that developed Zolgensma. All major insurance companies cover the treatment, he says, but one-third of them have criteria more restrictive than the FDA’s, which says any patient under 2 can have it. “It’s still very much an evolving marketplace,” he says. “We want to make sure the insurance companies and the community understand the gaps in coverage and help us address that.”

Novartis has been less forward about disclosing the potential manipulation of data in early Zolgensma animal trials, which it revealed to the FDA only the month after the gene therapy’s accelerated approval, three months after discovering the irregularities. The company has said it was conducting an internal investigation, and top scientists have left. The matter has drawn fire from lawmakers and the FDA has said civil and criminal penalties are possible.

Some insurers, including UnitedHealthcare, the nation’s largest, have changed their initial policies and now cover patients according to the FDA’s approval. Others, including Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield, continue to limit access only to those who show symptoms before they reach 6 months of age.

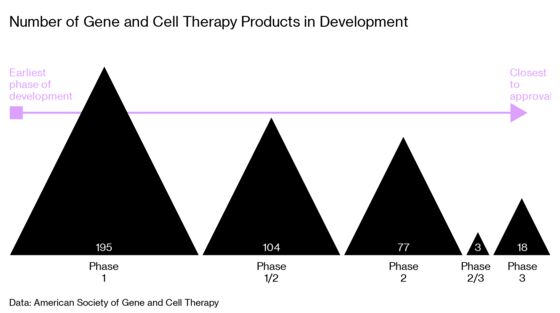

Here are six SMA patients whose parents have tried different approaches to make sure they thrive in preschool and beyond. (The insurers for these patients say they carefully consider coverage decisions.) Their experiences offer lessons for the many more people who will stand to benefit from all the gene therapies on the horizon: treatments for Parkinson’s disease, sickle cell anemia, and other more common conditions.

Battling the Insurer

Newborn screening gave Sarah and Logan Stanger, public school teachers in Monroe, Ohio, a heads-up that their son, Duke, had SMA in the spring of 2019. He was 3 weeks old and showed no signs of the disease that’s typically diagnosed after a desperate search for why a baby has stopped moving.

The Stangers and their doctors held off on giving him Biogen Inc.’s Spinraza, the only other treatment option, in hopes Duke could get the one-time gene therapy instead. Spinraza costs $750,000 for the first year of treatment and must be given every few months for life, adding up to $375,000 in annual drug costs in subsequent years. Duke wasn’t able to get into any early studies of Zolgensma, but his parents cried tears of joy when the FDA approved Zolgensma, assuming their wait was over.

The family has health insurance through the Butler Health Plan, which covers public school teachers and librarians in their county and is run by Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield. They didn’t know that the plan specifically excluded coverage for any type of gene therapy, regardless of disease, the patient’s age, or condition. Butler rejected the request to cover Zolgensma for Duke. The Stangers fought to overturn the plan’s gene therapy exclusion rule. But they didn’t know when or how their plea would be heard and were told they couldn’t attend the meeting where Duke’s case would be considered.

“It’s a tortuous thing to be told your child has this terrible genetic disorder and there’s this treatment out there, but we’re not going to cover it,” Sarah says. “It’s mind-blowing.”

The Stangers have reached out to the state health department and lawmakers. They’ve also had colleagues covered by the same insurance program write letters to the insurer. Friends suggested that the Stangers divorce and quit their jobs so their household incomes would drop enough for them to apply for Medicaid for Duke. Instead, they kept fighting, and the plan changed its policy earlier this month to include coverage of gene therapies. The family is still waiting to see if it will now cover Duke, who’s 5 months old and hasn’t yet shown any symptoms. “We work hard, we pay for our premiums, and we believe our insurance should pay for the treatment our child requires,” Sarah says.

Crowdfunding

Eliana was 8 months old when her parents, Shani Levi Cohen and Ariel Cohen, first realized there was a problem. “All the other kids were standing up in their cribs already and making their first steps, standing on the couch and falling, and my daughter was almost hardly crawling,” says Shani, a stay-at-home mom. Eliana’s doctor told her the milestones would come with time. They didn’t.

After a misdiagnosis, months of therapy, and scores of tests and procedures, the family was told Eliana had SMA in June. What she didn’t have was time. Zolgensma is a potential cure, but it’s approved only for children under age 2, before irreversible harm is done. Eliana’s second birthday was five weeks away. After insurance refused to cover the treatment, Shani and Ariel, a rabbi, turned to the Chesed Fund, a crowdfunding organization for the Orthodox Jewish community.

“As a mother, I have to do everything possible to help my daughter,” Shani said in a video that accompanied the family’s fundraising plea. “Everything, even if it makes me uncomfortable.”

So they reached out to strangers, and it worked. More than 23,000 people from the U.S., U.K., and Israel donated for Eliana’s treatment, mainly small amounts ranging from $5 to $180. One anonymous donor pledged $285,000 to bring the campaign over the $2.2 million target. It only took five days.

“I don’t know what the future will bring for her,” Shani says in the video. “I don’t know what machines, what tubes, what anything. All I know is that I want my daughter to have an opportunity to have a normal life, just like every other kid. I want her to be able to run and play in parks. I want her to be able to have friends.”

Eliana received Zolgensma on July 19, the day after her second birthday.

Immigrating

Portfolio manager Rajdeep Patgiri has been on a crusade for his daughter, Tora. She was born in the U.K., in September 2018. By January he and his wife, Taisiya Usova, a stay-at-home mother, noticed that she didn’t have much movement. He searched “baby doesn’t move her leg” on the internet, and the first few answers pointed to SMA. He took her to the emergency room, but the doctor said it was likely a developmental delay and sent them home.

Patgiri kept pursuing it, and two months later a neurologist gave him the dreaded SMA confirmation. There were no approved treatments for the condition in the U.K., so he asked his employer if he could move his family to the U.S. to get Tora into a Zolgensma study. Five weeks later, he relocated to his company’s New York office, though he’s been working remotely while the family has focused on getting Tora treatment in Columbus, Ohio.

Battling insurance wasn’t his initial plan. Patgiri tried to get Zolgensma through Novartis’s compassionate-access program, which makes experimental drugs available for free while they’re awaiting regulatory approval. But that was closed to them because he wasn’t a U.S. citizen or green-card holder. He applied for Zolgensma in June through his UnitedHealthcare insurance plan and was denied within days, because the insurer covered the drug only for children younger than 6 months.

But there was a wrinkle. On June 25, the day UnitedHealthcare sent Patgiri the denial, it also published new guidelines expanding use of the drug to children up to 2 years old. “I actually saw the new guidelines first, and two hours later I saw the denial, which didn’t make sense,” he says. After a weeklong review of Tora’s case, the insurer told him the reviewer didn’t have the authority to approve her treatment. So he shared their story with the Washington Post and other media while continuing the appeals process. A week after the story’s publication in newspapers, Tora was approved.

Compassionate Access

Sara Harlan has survivor’s guilt. The social worker is in the SMA Facebook groups, follows the news, and knows how much trouble some parents have had getting Zolgensma. For her daughter, Lucy, things weren’t quite so complicated, and she says that weighs on her. “I have a really, really hard time knowing how easy it was to get this stuff,” she says.

Lucy didn’t move much when she was born in Louisville in April 2018. She was diagnosed with SMA when she was 10 weeks old. She started on Spinraza within days and almost immediately started kicking her legs. “That was like hitting the lottery,” Harlan recalls. “We just screamed.” But the doctor had told her about Zolgensma, and she and her husband, Danny, an accountant for health insurer Humana, set their minds on gene therapy. The clinical trials were full. Around Thanksgiving, Harlan was scrolling through the posts in a Facebook group when she saw one from a father who’d been able to get the drug through Novartis’s compassionate- access program, the one for which Tora Patgiri didn’t qualify. Children in the program had to show symptoms or be diagnosed with Type 1 SMA, the most severe form of the condition, before they were 6 months old. Harlan immediately contacted her neurologist to secure approval, getting the final nod from the drugmaker on Jan. 2. Lucy received the therapy soon after.

Because she got Zolgensma through the drug company program and not through her father’s insurance, Lucy continues to take Spinraza, putting her in a new category of children getting combination therapy. Earlier this summer she did her first full roll, and she’s starting to lift herself into the crawling position. “We’re starting to see pretty remarkable changes,” Harlan says.

Medicaid

Maggie Moore’s experience getting gene therapy for her daughter, Margaux, in Birmingham, Ala., has been one of the most straightforward: The U.S. government’s health-care system entirely covered the treatment.

Moore, a stay-at-home mom, and her husband, Alex, a restaurant sous-chef, saw an abrupt decline in Margaux’s movement about a month after her birth in August 2017. They figured a quick call to the pediatrician would provide reassurance, but the doctor sent Margaux to the emergency room, where a neurologist on staff said, before any formal testing was done, that she had all the symptoms of SMA.

It took about a month to confirm the diagnosis with genetic testing. Although Maggie wanted to enroll her daughter in a study of Zolgensma, there were no open trials available, so at 4 months old, Margaux started Spinraza, covered by the federally subsidized state children’s health insurance program. There were signs the treatment was working: She could sit for brief periods alone and stand with support, though she still had trouble swallowing and needed help breathing at night.

The day Zolgensma was approved, Moore was on the phone with her doctor at Children’s Hospital in Birmingham asking for access to the treatment. They immediately applied for coverage from Alabama’s Medicaid program, which covers Margaux because SMA is considered a disability. In July, a month before Margaux turned 2, they got approval for her treatment. There were no hurdles to jump, only paperwork to complete.

“I had a perception that government insurance was less proactive,” Moore says. “They have been, from the beginning, amazing.”

Wrestling with the Choice

In Vinton, Iowa, Rani Hopkins struggled with the decision to get Zolgensma for her son LyRick, despite its being hailed as a miracle and a cure. He was born in November 2017, and she noticed problems with the way he was holding his hand by January. She took him to the doctor, where they learned he had an elevated heart rate. From there, LyRick ended up in the hospital and later with a neurologist who told Rani and her husband, L.C. Cannady, that their son had “perfect muscle tone” and that there was nothing wrong with him. But doctors don’t always figure it all out on the first visit. Two weeks later, LyRick’s condition was undeniable. “My son went from being what neurologists called a perfectly normal child to a limp baby,” Hopkins says. LyRick was diagnosed with SMA and given Spinraza through Medicaid a few days later.

He’s done so well on Spinraza that Hopkins is reluctant to change his regimen, even though it requires a lifetime of expensive treatments, not just one shot. Now a few months shy of 2 years old, LyRick rolls faster than most people walk, he talks, and he sits up unassisted. “I’m fighting with myself over this decision,” Hopkins says. “What if it doesn’t work? And we can’t get Spinraza? And he dies?”

She doesn’t have much time left for debate. Once LyRick turns 2, Medicaid, like other insurers, is unlikely to cover gene therapy.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net, Howard Chua-Eoan

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.