A Virginia City’s Playbook for Urban Renewal: Move Out the Poor

A Virginia City’s Playbook for Urban Renewal: Move Out the Poor

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The contours of inequality in Norfolk, Va., a city of 240,000-plus people at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, are clearly visible from atop the 26-story Dominion Tower. The tallest building in town houses its economic development office, a choice spot for officials to show off their city and to encourage visitors to envision its future.

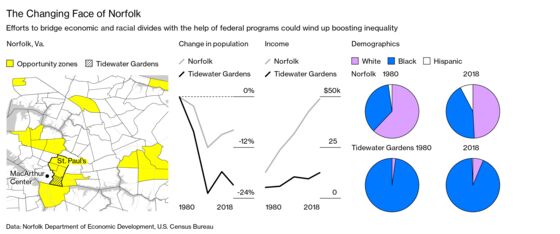

Look west, and you see a 300-room Hilton, a hockey arena, corporate offices for PNC Financial and payment processor ADP, restaurants and bars, a light rail station, and a one-million-square-foot mall. To the east is St. Paul’s, a 200-acre area north of the Elizabeth River that’s home to three public housing developments dating from the 1950s. The pitch-roofed, two-story, cinder-block houses are arrayed in rows like barracks. The two sides of the city are divided by a highway offramp that shoots suburban shoppers right into the parking garage of the MacArthur Center shopping mall and a six-lane boulevard that keeps St. Paul’s residents, mostly Black and mostly poor, a world apart from the downtown.

Jared Chalk, the director of economic development, admits the detrimental effects. “We’re working with the landlord to open up the mall a bit,” he says, surveying the view on a dreary February morning. Chalk and other city officials say they’ve tried to correct for decades of inequity with jobs and education programs. Critics, seeing a dearth of local businesses and jobs, deep poverty, and streets that frequently flood, say they haven’t tried hard enough.

Officials in Norfolk began weighing plans to demolish St. Paul’s public housing and replace it with mixed-use, mixed-income developments in the mid-1990s. But finding funds proved a challenge. Then came opportunity zones, a program that allows investors to defer taxes on capital gains by placing the money into a fund dedicated to investing in areas deemed distressed. Although it was enacted as part of President Trump’s controversial Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the provision enjoyed bipartisan support and bears the fingerprints of one of the economic advisers to Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden.

Once the legislation passed, Norfolk’s leaders wasted no time in reviving plans to remake St. Paul’s, with the city council in January 2018 voting 7-1 to raze the public housing developments. The next month, Mayor Kenny Alexander told Trump at a White House gathering that he hoped to use the opportunity zones program to transform the area. Virginia awarded Norfolk more zones than any other city in the state, meaning a “larger wealth of opportunity,” says Sean Washington, senior business development manager for the city.

After U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson visited in April, Norfolk was one of three cities in the country designated to receive a grant from the department to accelerate replacement of public housing. Norfolk hopes to leverage its $30 million haul into $150 million, including opportunity zone-eligible money. Out came the architect renderings of bustling, tree-lined streets, as well the promises that departing residents would be taken care of.

The first phase of the project calls for knocking down 618 homes in the Tidewater Gardens complex. About 220 units in the future development have been earmarked for families who want to return to the area and 83 others will be available off site. Construction is expected to take years, so in the meantime they’ll need to find landlords who accept federal housing vouchers, not usually an easy task.

City representatives say they’ve assembled a robust plan that includes helping residents secure new homes and providing support services such as job training and assistance with financial planning. “I’m confident that this will be the model of neighborhood revitalization going forward,” says Susan Perry, who’s leading the project for the city.

Paul Riddick, the only member of Norfolk’s eight-member city council to repeatedly vote against aspects of the redevelopment effort, has a different take. “Because of institutional and systemic racism, the African-American community is going to be pushed out again,” he says. “This is nothing but gentrification.” Riddick, whose ward includes St. Paul’s, figures that if the plan goes through, the share of Norfolk’s population that is Black will dwindle from more than 40% now into the mid-30% over the next 10 years.

Tanisha Daniels was 13 when she became overwhelmed with fear that her home could be demolished. It was 1999, and Daniels could see the glowing signs of the newly constructed MacArthur Center from her yard in Tidewater Gardens. Norfolk hoped to turn the shopping center into an anchor for a broader redevelopment of the downtown, including St. Paul’s. “I’m mostly concerned that my home will get torn down for a mall,” Daniels wrote in her submission to a local essay contest. “This is the only home I can remember.”

The long-heralded construction of the MacArthur Center had been yet another blow to the already shaky trust between the city’s leaders and the residents of St. Paul’s. Financing for the mall, built by billionaire tycoon A. Alfred Taubman, included an interesting perk: $33 million in loan guarantees from Bill Clinton’s Department of Housing and Urban Development for a Nordstrom store.

Initially the guarantees stipulated that the department store would make a concerted effort to hire residents from the area. But the arrangement was hardly ironclad: It required only that jobs be proffered, not that they be awarded. The local chapter of the NAACP was skeptical. “The use of anti-poverty money to underwrite an upscale, affluent department store does not normally fall within the realm of fighting poverty,” the organization wrote in a letter to HUD in 1994.

The NAACP’s concern was prescient. When HUD changed the rules so that Nordstrom would be required to hire 51% low-income workers, the retailer balked. “We simply can’t allow someone else to usurp our hiring process,” a high-placed executive at the company told the Virginian-Pilot newspaper in 1996. It was a huge blow to students attending the city’s program for retail job training, made possible in part by a Clinton initiative called enterprise communities that offered tax breaks and federal grants to spur investment in blighted areas. But rather than tussle with the retailer, Norfolk made up the $33 million of federal money with local financing, no strings attached.

The MacArthur Center got built, with few benefits for the residents of St. Paul’s, who mostly continued to shop at another shopping center 6 miles away. “I knew that was going to be a White mall,” says Daniels’s fiancé, Marco Madison, at a McDonald’s near their new apartment in Virginia Beach. Daniels eventually made her peace with the mall—she and her friends would walk through it on their way to the library—but her fear that St. Paul’s could disappear has stayed. “It’s been like a looming cloud,” she says.

The 34-year-old Daniels has the buoyancy and authority of a teacher, which is what she was studying to become when her parents died two years apart, leaving her the de facto parent of her extended family in Tidewater Gardens. She moved out a half-decade ago, but some of her relatives are still there. “At least it isn’t a mall,” she says through tears. “I guess this is progress?”

How Norfolk assumed its present form is a tidy CliffsNotes review of the history of federal economic development programs stretching to the end of World War II, when nearly 700,000 people streamed off returning ships at nearby docks. For White soldiers, there was the GI Bill, with its low-cost mortgages and loans and free college tuition. But the programs, administered by local officials, discriminated against Black soldiers. Redlining forced many to settle in neighborhoods in downtown Norfolk, where the housing stock and infrastructure were poor.

When President Harry Truman passed the Housing Act of 1949, the city’s all-White leadership volunteered to become a national test case for the program, razing the Black neighborhoods that they’d long maligned as squalid and rat-infested and replacing them with rows of identical homes set on tree-lined streets. The local chamber of commerce memorialized the transformation in an issue of its magazine, which included photographs of area residents collecting firewood or laundering clothes outdoors. “Scenes like this will soon be a thing of the past,” one of the captions trumpeted.

Public housing developments such as the ones in St. Paul’s were initially heralded as an historic opportunity to set low-income Americans on a path to middle-class prosperity. But the experiment was short-lived. By the 1970s, White residents in Norfolk and other American cities had begun fleeing to the suburbs, pushing metro areas into fiscal crisis. In Norfolk the loss of tax revenue was especially painful: About half the city’s land was already tax-exempt because of the presence of the Norfolk Naval Station.

With the advent of the so-called Reagan revolution in the 1980s, the political discourse on poverty underwent a marked change. Government handouts engendered economic dependency and paralysis, conservatives argued. Instead the public and private sectors should team up to create opportunities for Americans at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder to lift themselves up, rung by rung.

After Republicans lost their hold on the presidency, that sort of rhetoric found a new champion: Bill Clinton. In his 1996 State of the Union, Clinton boasted that his administration was cutting welfare rolls, and he asked Congress to deliver a bill that would make requirements even more stringent. “The era of big government is over,” he said.

In 1993 his administration had begun designating empowerment zones and enterprise communities, distressed cities and regions that were slated for a boost, using private capital lured with tax breaks. Empowerment zones would come to define the next quarter-century of federal economic development, as public assistance to the poor plummeted and new “place-based” investment programs were drafted into being. After making it onto the inaugural list of enterprise communities, Norfolk lobbied hard for an empowerment zone designation, earning the title—and the enhanced tax breaks that came with it—in 1999.

Opportunity zones are the most souped-up place-based program yet. Where the Clinton programs offered employment credits and meager grants meant to act as catalysts for private investment, opportunity zones offer large breaks on capital-gains taxes for investors who build properties in the almost 9,000 areas that have been designated “distressed.”

The idea came from billionaire Sean Parker, who was sitting on a mound of founders stock in Facebook Inc. He was looking to sell and diversify, except doing that would trigger a huge tax bill. To help build support for his brainchild, he co-founded a think tank in 2015 called the Economic Innovation Group. Its advisory board includes Jared Bernstein, who’d been Biden’s counselor on economic matters during his years as vice president. EIG’s mission, according to its website, “is to advance solutions that empower entrepreneurs and investors to forge a more dynamic economy throughout America.”

In 2018, as the buzz about opportunity zones began to build, members of Norfolk’s economic development team struck up a relationship with Bruce Katz, a Clinton administration alum who led President Obama’s housing and urban development transition team. Katz is helping Norfolk drum up business in other areas of the city, says the development office’s Washington, including new plans for Military Circle, the mall that many St. Paul’s residents have long favored.

For the St. Paul’s project, Norfolk tapped Brinshore Development LLC, which had a hand in redeveloping the property in Chicago where the Cabrini-Green public housing development once stood. Richard Sciortino, a principal at the company, says Brinshore takes its duty to field input from the community seriously. “There’s racial mistrust that comes with these projects,” he says. “It takes time to get people to feel comfortable that you’re going to do what you say you’re going to do.”

Last September, Norfolk was one of five cities picked to partner with the Rockefeller Foundation to deploy opportunity zones in sustainable and socially inclusive ways. The city is hoping to train residents for jobs in the construction phase, with the hope that those skills will transfer over to the city’s other industries, such as shipbuilding, afterward. “We don’t want people to think this is just a real estate play,” Washington says.

After Norfolk began the process of moving residents out of Tidewater Gardens in August 2018, tenant group president Marquitta White found herself doling out unsentimental advice about the arcane processes that govern the distribution and use of housing vouchers. “If you don’t know anything, it doesn’t mean you’re not going to move. It just means you’re not ready,” she says.

In February this year, as the number of vacated homes eclipsed 100, residents began noticing that some were getting broken into and squatters were moving in. Suddenly some who’d been in no hurry to leave were looking to do so as soon as possible. The process of emptying out the community carried on even as the pandemic raged, until the city imposed a six-month moratorium on forced moves in May.

White, a trained chef, was running her own catering business when in August 2017 she broke both legs and fractured her neck in a car accident. She recovered, but it was a lengthy process that weighed on her finances, which is how she and her two daughters wound up in Tidewater Gardens. The end of St. Paul’s, she says, is part of a broader trend: the methodical dismantling of what’s left of the U.S. welfare state. “Public housing, social security, Medicaid—all that is going away,” she says, as she organizes supplies in the Tidewater Gardens tenants office.

What rises up from the ashes of Tidewater Gardens is of little concern to White. “I don’t know anything about the project,” she says. “All I know is I am the project.” White is a meticulous record-keeper, diligently logging phone calls with officials and document filings, and she encourages her fellow tenants to do the same. “The Bible says, ‘Trust no man,’ ” she says. By April, White’s work at Tidewater Gardens had garnered the attention of the city, and she was added to the community outreach team of Urban Strategies Inc., the third-party outfit the city hired to manage the move-out process. “That was smart of them,” she says with a laugh.

East Ghent. Broad Creek. Church Street. Councilman Riddick rattles off the names of the various parts of town that Norfolk has “revitalized”—the result in each case being fewer Black residents. “They were told they were going to be allowed to come back,” Riddick says of residents who were displaced in East Ghent, where the city bulldozed Black neighborhoods in the 1960s, a process some still call “Ghentrification.”

In January a progressive group called New Virginia Majority filed a lawsuit seeking to halt evictions from Tidewater Gardens, alleging the city had a “long and indisputable history of racial segregation in housing.” When the city halted evictions in May, New Virginia Majority’s lawyers worked with city officials to hammer out the terms: no move requirements for 180 days, extensions to use already issued vouchers, and acknowledgment that the city still needs to maintain the remaining homes. “This pandemic has amplified how particularly vulnerable this community of folks is,” says Lafeetah Byrum, a community organizer with New Virginia Majority.”

Residents are grateful for the pause, but Riddick argues that a true victory would be getting city officials to approve the construction of public housing elsewhere in the city before the demolition work begins. “We have enough land in Norfolk to house everyone in Norfolk right now,” he says.

Earlier this month, Norfolk received another federal grant: $14.4 million from the Department of Transportation to redevelop the roads that have cut off St. Paul’s for so long. It will help connect the redeveloped neighborhood to the rest of the city.

Meanwhile, St. Paul’s as it exists today is set to become history—or at least a piece of it. A planned greenway to curb flooding will include a “cultural trail” highlighting the neighborhood and the contributions of its residents. “They want to make Norfolk look like Virginia Beach,” Daniels says, referring to the neighboring city across the water, which is one-fifth Black. “Plow our history over.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.