When Bakers Demanded More Flour, King Arthur Went to the Mills

When Bakers Demanded More Flour, King Arthur Went to the Mills

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On March 18, Bob Morando, the chief executive officer of a flour mill located in the pancake-flat wheat fields of central Kansas, received a short, cryptic text from Brad Heald, the director of mill relations for his biggest customer, King Arthur Flour Co. “Call me,” it read.

Morando had an idea what Heald might want. Locals had been showing up at the mill all day in frantic pursuit of flour after finding it sold out at nearby grocery stores. When Morando called, Heald asked what it would take to get his whole-wheat flour mill, Farmer Direct Foods Inc., to double its output. King Arthur, one of the country’s largest flour companies, was running dry.

Mid-March is normally when a mill such as Morando’s slides into its annual slow period, as the weather warms and home bakers step away from their ovens. But fears were rising about the spread of the novel coronavirus. Cities across the U.S. were implementing unprecedented school and business closures, and shoppers were preparing for weekslong quarantines like the ones they’d seen on news reports from China and Italy.

Anything that could be hoarded flew off the shelves—pasta, toilet paper, canned soup. Among the staples in highest demand was also, unexpectedly, flour. The American public seemed to reach a collective understanding that baking, with its soothing rhythms and hint of homestead self-reliance, was just the thing to help ride out a stay-at-home order.

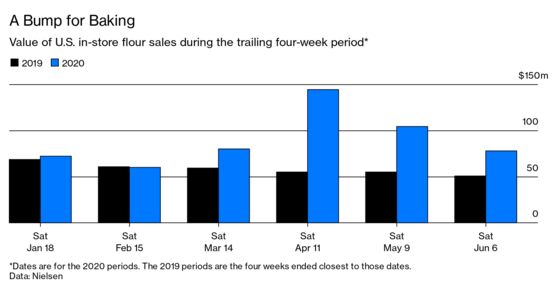

King Arthur’s retail flour sales almost tripled in March; in some grocery stores, when shipments arrived, shoppers picked the pallets clean before anything made it to the shelves. In two weeks, the entire “safety stock”—essentially, the company’s strategic flour reserve—was depleted, and so were baking aisles across the country.

After four decades in the cereal grains industry, Morando never expected to find himself facing down a national flour shortage. To meet it, though, he’d have to square his responsibilities to King Arthur, and to the American public, against his unease about Covid-19 and what might happen should it find its way into the mill. “I’m over 60, and a couple of my other guys are over 60,” Morando says. “We thought, Oh boy, if I got sick with this I might die. But what the heck. You gotta do it. You’re in the food industry.”

King Arthur Flour opened for business in 1790, during George Washington’s first term as president. It’s America’s oldest flour company and one of its oldest manufacturers. Over the centuries, King Arthur developed a loyal following among bakers. Priced a bit above the competition but without artisanal pretensions, it’s the Cadillac of flours.

At the heart of the company’s approach is wheat sourcing. It pays extra for wheat that’s especially high in protein—the critical element for giving baked goods a nice, proud rise. The 45 mills that make King Arthur flour, including Farmer Direct, meticulously blend each variety to get the protein ratio consistent within two-tenths of a percent. King Arthur all-purpose flour clocks in at a sturdy 11.7%, a figure that’s printed right on the front of the bag. The resulting breads are light and airy; the cookies don’t spread too much on the tray. “I’ve always found King Arthur flour to be superconsistent in its quality,” says Karly Kuffler, executive pastry chef at Le Crocodile in New York. “It’s also accessible. My mom taught me how to bake with King Arthur, and here I am using it in the professional kitchen today.” The flour is never bleached, lending it a creamy, natural appearance that sets it apart from its bright-white competitors.

For much of its history, King Arthur was content to dominate the New England market. It’s only in the past few decades that it expanded nationally and began focusing on building a deeper, direct connection with bakers. Brinna Sands, the wife of Frank Sands—whose family owned the company from 1870 to 2004—was adamant that King Arthur not simply sell flour but become an educational resource for bakers, too. The couple established a headquarters in Norwich, Vt., nicknamed Camelot, that featured a baking school, a cafe, and a store. It’s become one of the state’s biggest tourist attractions.

The independent, values-driven approach carried on after the Sands family sold the company to its employees in 2004. King Arthur became a certified B Corp three years later, recognizing a long-standing commitment to its local community, the education of bakers, the environment, and progressive employment practices. Annual sales have risen from a bit more than $4 million in 1984 to about $150 million in 2019, making it the second-bestselling U.S. flour brand, behind only Gold Medal from General Mills Inc.

As the business’s fortunes have grown, the Sands family’s commitment to baking education has continued to flourish. King Arthur has published three cookbooks, and it offers more than 1,000 recipes on its website—gateways to a thriving e-commerce operation where you can pick up whole-wheat pastry flour, Indonesian cinnamon, or a baguette pan. For 20 years the company has also run a hotline staffed by experienced bakers, who field thousands of calls each month from customers fretting about proofing temperatures or recipe substitutions. An equally knowledgeable team tackles questions and comments that come in through social media.

When the pandemic struck, those channels were flooded with requests. “Just as demand for flour has gone up two to three times, so has the amount of consumer inquiry, whether it’s ‘Help me to bake’ or ‘Where can I get flour?’ ” says Karen Colberg, one of King Arthur’s co-CEOs. The company’s unusually close ties to customers made the thought of leaving bakers in the lurch feel personal. Colberg and her co-CEO, Ralph Carlton, committed themselves to filling the breach.

King Arthur quickly added a fourth distribution center to keep up with its ballooning e-commerce orders. It also added a second shift at a facility on its Norwich campus that makes baking mixes and bags flour milled elsewhere, retraining staff from the now-closed cafe and store. A dozen teachers from the baking school moved over to the hotline and social media teams, working remotely from their homes to handle a spike in inquiries to double the normal volume. “The number of sourdough baking questions has been just huge,” says Linda Ely, who works on the hotline. “Why isn’t my sourdough growing? Did I kill my starter? What kind of flour can I feed it?” The bakers were skewing younger and less experienced than her typical callers, asking questions about how to measure ingredients and whether long-forgotten bags of flour in the freezer were still usable (usually, no). “We’ve been getting a lot of people who are new to this,” Ely says.

Beyond advice, what bakers really needed was flour, and that came down to the mills. There was no shortage of wheat: The U.S. grows 2 billion bushels (about 120 billion pounds) per year, less than 2% of which becomes retail flour. Even an astronomical increase in consumer demand represented a small share of the overall market.

The bottleneck lay in the limited number of manufacturing lines set up to package flour into the 2-, 5-, and 10-pound bags destined for grocery shelves. Of King Arthur’s 45 mills, only 7, including Farmer Direct, are equipped with the required machinery. The rest ship flour by the truckload or in industrial-size bags direct to commercial bakeries, food manufacturers, and restaurants. Building and installing machinery would mean enormous expense and take more than a year to complete.

The key instead was to get all the retail packaging lines in King Arthur’s network to drastically increase output. Milling and packaging are highly automated; it takes only four shift workers to operate Farmer Direct’s 10,000-square-foot mill. (Social distancing, thankfully, isn’t a problem.) That meant Morando could double his flour output simply by hiring four new employees and operating a second shift.

Those jobs, however, are highly skilled. To fill them, Morando leaned on Kansas’ tight-knight milling community. “We call ourselves the Kansas mafia,” he says. He brought back a few retired employees and hired a couple of recent graduates of Kansas State University’s milling science and management program, the world’s only four-year degree in grain milling. In less than two weeks, Farmer Direct went from operating one shift five days a week to double shifts six days a week.

With all seven mills bagging flour at full tilt, King Arthur found one more way to increase production. Two of the company’s mill partners had lines sitting idle that had been set up to pack 3 pounds of baking mixes into resealable plastic pouches. King Arthur had never sold flour in that kind of package, but it swiftly designed a plastic pouch that could be filled with the same weight of all-purpose flour and got manufacturing under way within weeks. The solution promises to add up to 1 million bags of flour to the company’s inventory; it’s already on sale, exclusively on King Arthur’s website.

As quarantine measures ease, the question on everyone’s mind is how long the baking renaissance will last. Will the unprecedented demand for flour continue through the summer? Longer? If the economic downturn brought on by the pandemic continues, retail sales could remain elevated. King Arthur saw a 25% increase during the 2008 recession, when people ate out less and turned to home baking as an affordable indulgence.

As of now, the company plans to keep retail production ramped up through the end of the year. Carlton, the co-CEO, predicts that even as the pandemic risk recedes and more activities resume outside the home, people newly initiated to the joys of baking will continue with it. “There’s a whole new generation of people baking from scratch for the first time,” he says. “The circumstances are not ones we like, but that learning experience is very exciting.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.