American Indian Tribe Becomes a Player in the No-Money Mortgage Business

American Indian Tribe Becomes a Player in the No-Money Mortgage Business

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Richard Ferguson considers himself the friend of struggling homebuyers everywhere. The Utah mortgage man will make families’ down payments for them. That way they can qualify for loans backed by the Federal Housing Administration. And they are—in droves, borrowing as much as $100 million a month.

Ferguson runs the Chenoa Fund, which is owned by American Indians, Utah’s Cedar Band of Paiutes. “Chenoa” is thought to be a native American word for peace, but operations like Ferguson’s are raising concerns in the industry and in Washington. That’s because he’s running a company with a dual role, not only providing the down payments for borrowers across the country but also profiting from making the loans by charging above-market rates and fees. Some members of the tribe say they’ve seen little or no benefit from the business and question where the money is going.

In the 2000s, Ferguson ran a similar program, which allowed home sellers to in essence fund buyers’ down payments. Congress later banned such operations, which ended up costing the FHA’s insurance fund $17 billion when borrowers got in trouble. “When things went south in the last downturn, those folks were riskier—they defaulted at much higher rates,” says Joe Gyourko, a real estate and finance professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “Ultimately, we forget and go back and make the same errors.”

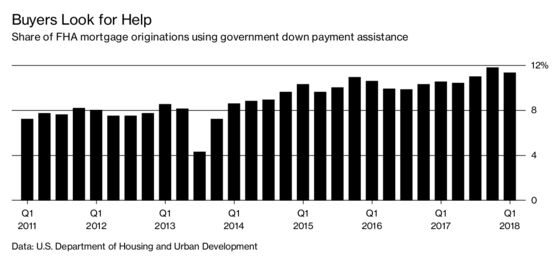

Ferguson’s resurgence is part of a broader proliferation of down payment programs, which is raising questions about the health of the $1.2 trillion government-backed FHA loan portfolio. Borrowers pay fees toward a fund insuring the mortgages, but in 2013 taxpayers had to bail out the FHA. Down payment help—including from relatives—now enables 4 in 10 FHA loans. Borrowers who get such assistance from government programs become delinquent at about twice the rate of those who put up their own cash.

This fall the FHA is taking a hard look at some down payment programs, singling out “tribal providers” for potential new regulation, according to a government filing. Ferguson says his organization, one of the biggest down payment assistance programs in the U.S., is the only American Indian-owned provider offering loans to nontribal borrowers.

After the 2008 housing crash, Congress prohibited down payment assistance from any party with a financial interest in a transaction. But the FHA’s ban didn’t apply to federal, state, and local government programs, which now make up the majority of the 2,500 U.S. down payment assistance outfits. “The rationale is that state and local housing finance agencies have a commitment to their own citizens, so they wouldn’t want to overcharge them,” says Meg Burns, former director of single-family program development at the FHA and now a senior vice president at the Housing Policy Council, a mortgage-industry trade group. Burns says the Chenoa Fund might run afoul of the FHA.

Ferguson says he complies with all FHA rules. He points to one from 2007 that exempted tribes from the ban along with other government entities. Those regulations were set aside by a court. Newer ones don’t specifically mention tribes, but Ferguson says the 2007 language shows tribes are meant to be exempt.

Ferguson operates the program from an office building with a stone facade in South Jordan, a town about a 20-minute drive south of Salt Lake City that’s framed by the violet-hued Wasatch Mountains. He grew up in Utah and earned an economics degree from Brigham Young University. On a recent weekday morning, he pulled up to Chenoa Fund’s headquarters in a purple Lincoln sedan. A backpack slung over his shoulder, he was dressed casually in a red polo shirt and jeans.

Ferguson says he’s offering families access to homeownership as rising home prices put the American dream out of reach for all but the wealthy. Many can’t afford even the modest FHA down payment, 3.5 percent of a home’s price—or if they can, it would wipe out their savings for a rainy day. African Americans make up 20 percent of Chenoa Fund borrowers, and Latinos 28 percent, he says. “We need to get qualified people into homes sooner so they can enjoy that appreciation,” he says. Some of the fastest-growing U.S. mortgage lenders, including California-based LoanDepot Inc., have worked with the Chenoa Fund, soliciting customers and putting together deals.

More than five years ago, Ferguson and his team met with Thomas Sawyer, who then oversaw the Cedar Band’s business operations, and suggested a new down payment assistance program. The band’s other ventures, operating through a company called Cedar Band Corp., include an information technology company and a wine company.

Ferguson and his management team collect a cut of the gross proceeds of the Cedar Band’s mortgage business, says Sawyer, a former Indian affairs adviser to four U.S. presidents. Ferguson has been making a hard sell. He just celebrated completing 10,000 loans in three years. “You no longer have to wait for a down payment to buy your home,” reads a Chenoa flyer made to look like a $10,000 bill. “Start building wealth today—home prices are increasing monthly.”

As is typical of many government down payment programs, borrowers pay higher interest rates and fees than standard market fare. That allows the organization to resell the loan to investors at a premium and generate revenue for its operations. The Chenoa Fund holds a second mortgage that takes the place of a down payment. Customers have the option of paying a market rate on the first mortgage and a higher one on the second. Only one-third choose to do so, Ferguson says.

To lower the risk of such loans, Chenoa offers a year of counseling and monitoring, he says. In addition, the loans meet stringent government guidelines, and two independent parties review them. A second-loan forgiveness plan rewards some customers who make three years of on-time payments, he says.

Nancy LeMessurier, a loan adviser with American Pacific Mortgage Corp. in Gig Harbor, Wash., says she was surprised when she looked into Chenoa for a buyer in March. The Chenoa rate at the time was more than 6 percent, so she found her client a cheaper option. “The price to obtain the loan outweighs the amount of the down payment,” she says. Some Chenoa programs give customers a better rate than the one LeMessurier is referring to.

Borrower Miguel Benitez says Chenoa met his needs. A maintenance worker married to a hospital housekeeper, he has no savings, $50,000 in family income, and a poor credit score after a bankruptcy. The Chenoa Fund helped him buy a home for $130,000 in April. “We live check to check,” he says. “I didn’t care how high or low the rate was. The point was we needed a house, and we got the house we wanted.”

Ferguson is using the playbook he pioneered at the Buyer’s Fund Inc., a nonprofit founded in 1999. It grew to be one of the largest down payment programs in the country, bringing in $167 million in revenue with 31,000 loans in 2004. The fund gave down payment money to buyers that was funded by fees from sellers. (At Chenoa, sellers don’t fund down payments.) Neighborhood Gold, a for-profit company of which Ferguson was a minority owner, was paid as much as $12 million a year to market the program. Ferguson left the Buyer’s Fund in 2002 and sold his stake in Neighborhood Gold in 2004.

In 2006 the Internal Revenue Service called some ostensible down payment charities “scams,” saying they were “self-serving, circular-financing arrangements” designed to circumvent the prohibition against seller funding. It later revoked the Buyer’s Fund’s tax-exempt status. Ferguson disputes the IRS characterization of such programs, saying the agency had initially blessed them.

In a 2005 lawsuit, a former president of the charity accused Ferguson and other partners of diverting millions of dollars for their own benefit. The money included church tithes. They denied the allegation. Ferguson says he and a partner asked that some money due them go instead to the church. He says two reviews commissioned by an independent board found that the money his company received represented fair compensation, though another said the cost was too high.

Ferguson reached a private settlement after a district court judge dismissed most of the claims, saying the plaintiff lacked standing in the case because he wasn’t a director of the Buyer’s Fund at the time of the suit. “I have always sought to govern my life with honesty and integrity,” Ferguson says. “As the resolution of this matter ultimately showed, any errors made were due not to lapses in judgment, but rather from a young man’s lack of understanding of the complex nature of the business world.”

On his LinkedIn page, Paul Terry, Cedar Band Corp.’s chief executive officer, said revenue for all the Cedar Band company’s businesses jumped to $52 million last year, from $3.4 million in 2014, the year after the Chenoa Fund was founded. Terry cited a $14.3 million profit, up from a loss of $1 million three years earlier. Ferguson says the Cedar Band has received millions of dollars from Chenoa. Along with small per capita payouts on holidays, he says, the money will fund expenses such as health care, education, and job training. Ferguson won’t disclose his pay or details of his company’s finances, but says he isn’t getting rich.

But some of the roughly 287 members of the band say they’re in the dark about the success of its businesses. On a recent afternoon, the Paiute reservation, which stretches beneath red cliffs on land scattered with sagebrush, was hardly abounding in fresh riches. Near Cedar Band Corp.’s headquarters, Delice Tom, a tribe member who’s married to a retired railroad worker, points to a series of mobile homes in various degrees of disrepair. Tom and other critics say they’ve been stonewalled by the corporation they own for more than five years as they seek information about its finances.

Tensions have split her family apart. She says she often fights with siblings, nieces, and nephews who serve on the band’s governing council. “We’re not seeing any of the money,” she says. “I’d rather have these businesses shut down so at least there’s no arguments among us.”

Tom drives 15 minutes to her one-story brick house, one of about seven government-built homes on reservation land on the outskirts of Cedar City (population 32,000). On the way, she passes billboards for gas stations and hotels, which for years were the main revenue source for the band. The Cedar Band smoke shop sells tax-free cigarettes and chewing tobacco, fireworks, and groceries. The band owns 2,200 acres, most of it hilly and unsuitable for development.

Another member, Elvis Wall, lives in a 50-year-old single-wide trailer that he’s repairing. A U.S. Navy veteran, the retired Bureau of Land Management worker is the son of farm laborers. He’s skeptical about how the money is being used. “They’re using our last resource for their economic ambitions—our sovereign rights,” Wall says. Members do get dividends in the form of Christmas bonuses from the mortgage company and other businesses. The most recent sum: $100.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: John Hechinger at jhechinger@bloomberg.net, Pat Regnier

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.