How a Foreign Investor Rattled a Tiny African Kingdom’s Economy

How a Foreign Investor Rattled a Tiny African Kingdom’s Economy

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Mohlalefi Moteane runs his wool and mohair brokerage out of his veterinary practice, housed in a small building on a dirt road in Maseru, the ramshackle capital of Lesotho. When a young Chinese businessman visited in 2012 asking to join the business, Moteane turned him away. He saw no need for taking on a partner he didn’t know.

Six years later the same businessman, Guohui Shi, and his Lesotho Wool Centre were awarded a monopoly over the wool and mohair trade in the Southern African mountain kingdom, meaning Moteane and other small brokers would have to shut down. Since then, thousands of farmers have had to wait a year or more to be paid by Shi’s brokerage; some say they’ve been underpaid, and others not paid at all. Approximately 75% of Lesotho’s population lives in rural areas and relies on wool and mohair for income. Some herders have been forced to eat their flocks to survive.

At $67 million, Lesotho’s wool industry is small but significant for the impoverished nation. It dates back to the 1850s, when migrant workers returned to Lesotho from South Africa, which encompasses the tiny country, with merino sheep. Today, Lesotho is the world’s second-biggest mohair supplier; it controlled 17% of the global supply in 2017. The sheep are an ever-present sight in the country, as are Angora goats, whose soft coats are used to make mohair. Herds graze on the roadside in Maseru, and shearers set up makeshift stalls on the sidewalk, where farmers bring their flocks.

Aside from wool and mohair, Lesotho has little in the way of industry. There are a few Chinese-owned textile plants, and the government exports water to South Africa. Per capita gross domestic product is about $1,200, but farmers can earn as little as $265 a year.

For four decades before the government awarded the wool trade to Shi, farmers typically took their fibers to South Africa to be auctioned off. South Africa’s BKB Ltd., headquartered in the Eastern Cape city of Port Elizabeth, once dominated the trade alongside a handful of smaller competitors, including Moteane’s business. Farmers were usually paid in about six weeks. “Why do you create this kind of legislation in the first place, when the farmers have never complained?” asks Moteane while rifling through newspaper cuttings about the Chinese businessman. Farmers and the group that represents them, the Lesotho National Wool and Mohair Growers Association, say they weren’t consulted by the government before it awarded the monopoly. Lesotho’s debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to be 49.5% for the current fiscal year, up from an estimated 38.8% in 2018.

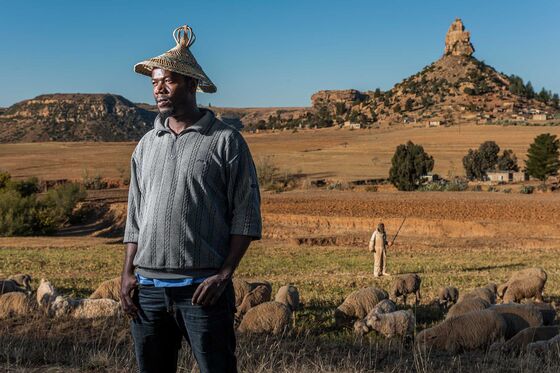

In a grassy valley below the rocky outcrop of Thaba Bosiu—the onetime mountain hideout of King Moshoeshoe I, who founded Lesotho—a tall 38-year-old farmer named Leketla Seqhee looks over his herd of 37 sheep and seven Angora goats. While he still employs shepherds to tend them, others have fired theirs. He’s struggled to pay his children’s school fees. “They have cheated us, they didn’t pay us,” he says in Sesotho, Lesotho’s dominant language, of the Lesotho Wool Centre. The farmers’ problems have been caused by “these harsh laws by our government. We struggled a lot. We are still struggling,” he says.

Little is known about Shi—who goes by Stone Shi, a play on the meaning of his surname—and how he won the monopoly. After being turned away by Moteane, he began working with the Lmwmga, the farmers’ group. While Lmwmga partnered with Shi to build the Lesotho Wool Centre, it says it derives no benefit from the brokerage business and did not agree to the monopoly. “We haven’t got any money from mohair. Zero,” says Mothibeli Makhetha, a farmer and an officeholder at the Lmwmga. “We are angry with the government because it is the one that pushed us to work with Stone Shi, even though we are not on good terms with him.”

Communications Minister Thesele Maseribane, who also leads a party in Lesotho’s ruling coalition, says Shi is one of the few foreign investors in the country and needs to be “protected.” He also says that having the wool sold by a company based in Lesotho is “good policy” because it would lead to more tax revenue and greater employment.

Shi’s Lesotho Wool Centre, a few miles from Seqhee’s farm, consists of a 108,000-square-foot warehouse eerily empty but for a few bales of wool in one corner and a pile of mohair bales in another. There’s little visible equipment and few workers. Shi initially agreed to an interview, but when the day arrives, a representative says he’s out of the country. He doesn’t answer calls to his mobile phone or reply to questions sent by text message.

John Koenane, the company’s head of information technology, answers questions instead. “We have paid most of the farmers,” says Koenane, adding that 379 million maloti ($25 million) has been paid out for last year’s harvest. That compares with normal annual income of 800 million to 1 billion maloti. When an assistant asks Koenane what to tell a farmer who found no money in his account, he says the farmer should check back in a week.

The payments have been delayed, Koenane says, because samples of wool and mohair had to be sent to New Zealand to be tested for the fineness of the fiber after a South African industry body refused to do it. The wool is auctioned online, mainly to anonymous Chinese buyers. Koenane says he can’t disclose the buyers’ names for “political” reasons. Export documentation shows that at least some of the wool exported by Shi goes to Yulian Wool Industry Co. in Jiangbu, China. Calls to that company weren’t answered.

Wian Heath, the managing director of the Wool Testing Bureau of South Africa, says Shi declined to bring full bales of wool and mohair to be tested. At the South African auctions, the names of the buyers and the amount they purchase is disclosed, wherever they’re located.

Many farmers have yet to shear their sheep and goats this year because they aren’t sure they’ll be paid. Others have taken to smuggling the raw fiber over the border into South Africa. With Lesotho’s ruling party split, and a possible no-confidence motion against the prime minister likely to trigger an election in the near future, politicians fear a backlash from farmers. In June, thousands who said they hadn’t been paid for their sheep and goat wool staged an unprecedented march on Parliament.

Two months later the government eliminated the monopoly, but it’s still insisting that the fibers be auctioned locally. Brokers say this is unrealistic because on its own, the amount Lesotho produces is too small to attract international buyers. “There was a lot of noise from farmers, lots of problems. All of them are angry,” says Kimetso Mathaba, an opposition lawmaker and the head of a parliamentary committee that’s looking into the matter. “Mr. Stone has told us his side of the story. We heard what he said. It was very different from what the farmers and associations are saying.”

The biggest question, still, is how Stone Shi managed to persuade the country to entrust him with its biggest export. “Who is this fellow?” asks Moteane. “I still want to know.” —With Sarah Chen

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net, Jillian Goodman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.