Houston Had an All-American Pandemic Response: Ignore Until It’s Too Late

Houston Had an All-American Pandemic Response: Ignore Until It’s Too Late

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s Friday night in Houston: 9:30, 102F, 90% humidity, and the patio at Flava Restaurant & Bar is packed. Friends are sucking on hookahs. Waitresses hustle by in booty shorts. Someone climbs on a picnic table to twerk.

The place looks over capacity. Owner Louis Watson knows it. Houston Covid Task Force Chief Keith Kennedy knows it. And judging from the expression on his face when Kennedy rolls down his tinted window, the valet knows it, too.

In the rearview mirror, I watch the valet hustle over to the bouncer, who calls Watson over from his perch on a railing beside the DJ. By the time Kennedy, who’s also the chief arson investigator for the Houston Fire Department, has parked and made his way to the entrance, Watson is outside with a light blue folder spread open on the hood of a matte black Jeep Wrangler.

When the pandemic started, Watson was a young Black businessman coming into his own, with a corner property on the Richmond Strip, not far from the moneyed Galleria Area and near Polekatz and La Bare, two of Houston’s better-known strip clubs. His main concern now is no longer just beating the competition—it’s also avoiding being shut down or fined into extinction by the tangle of rules officials have deemed necessary to keep Houstonians from dying of Covid-19.

“I am abiding by all state, county, and city regulations,” Watson says before Kennedy can get in a word. “And my adherence to those rules is in compliance with the governor’s executive order GA-28, which reads here as follows: ‘Every business establishment in Texas shall operate at no more than 50 percent of the total listed occupancy of the establishment.’ ”

Kennedy hooks his thumbs on his belt, looking amused.

“So here under Section 12: ‘People should not be in groups larger than ten and should maintain six feet of social distancing from those not in their group.’ ” Watson waves a finger in the air. “Except! Do you see here how it says, ‘Except?’ ” The word “except” has been conveniently highlighted in yellow. “So then we turn to the exception,” he says, flipping a page.

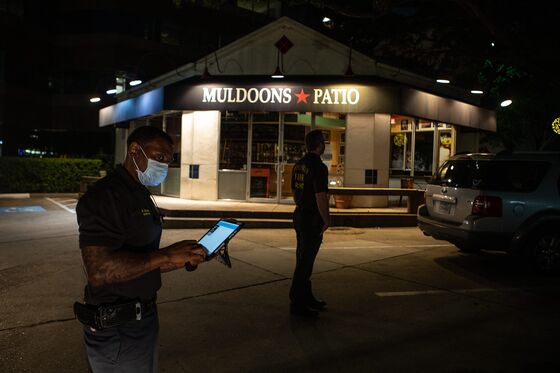

Watson sweeps his hand to indicate the patio and argues that, because fewer than 100 people are there, it can be over half full. Kennedy lets Watson finish making his case, then issues a verbal warning and promises to return next weekend. “Our job is to enforce,” Kennedy says later. “But we’re gonna shut down businesses? We’re gonna make citations when people are hurting?”

The first big sign that the pandemic had arrived in this city of 2.3 million was quintessentially Texan: The world’s biggest rodeo was canceled. Specifically the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, an annual extravaganza that kicks off with a freeway horseback ride into town and spans 28 days of mutton-busting, barbecue contests, and 75,000-strong crowds. The festivities were well under way, with my goatskin boots all polished up for the party, and Willie Nelson and Lizzo were days away from performing, when Mayor Sylvester Turner declared a public-health emergency and announced that all city-sponsored events would be suspended. It was March 11, and there were 14 reported local cases.

Many people thought Turner was overreacting, but in retrospect we were kidding ourselves. It’s not as if we didn’t see what was happening in New York or five hours away in New Orleans, which had suddenly become an epicenter. Signs on the freeway told us “Personal travel from Louisiana must quarantine,” and still, for some reason, we thought the pandemic wouldn’t really touch us.

Then came reports, in late May, that intensive care units were nearing capacity. But that, too, seemed implausible in a town rife with world-class medical facilities. Businesses closed, then tried to reopen, then reclosed. By July 4, there were 566 deaths. On July 31, 1,664. It turned out there’d been more cases in our city than we knew: A Houston Chronicle investigation later showed that at least three dozen people who were symptomatic before the first reported Covid-19 case later tested positive. Three of them died.

I’m from Houston, but I was supposed to be back only briefly this spring before returning to Brazil, where I’ve lived and worked for much of the past decade. Instead, with my return on hold, I found myself spending months wandering an uncannily quiet, traffic-less city. As the bad news mounted, I saw Houston fumble to grasp the gravity of the situation. With temperatures rising high enough that the air above the asphalt wobbled, Houston slipped into a delusional state, a kind of public-health fever dream. We’d pack restaurant patios in the shadow of filled hospital skyscrapers, complaining about business closures as ambulances screamed through empty streets. Houston never quite got a handle on the pandemic; like much of the country we just assumed things would improve as time ticked by.

I witnessed it play out the way any good Houstonian would: by hitting the freeway. The city’s rings of highways, 38, 88, and 170 miles around, are crosscut by even wider interstates, one of them 26 lanes across, the widest in the world. Any given exit will deliver you to a different shade of Houston; these days it will also bring you to a different shade of Covid.

My first stop is just inside the southern curve of the Inner Loop. Down the block from Rice University lies Ben Taub Hospital, a 444-bed Level 1 trauma center, one of the country’s busiest, with an ER that handles 80,000 patients a year. Many of those who come in are uninsured, as 17.7% of Texans are, the highest share of any state.

The hospital has been at capacity since early March, when Esmaeil Porsa came on as president and chief executive officer of the Harris Health System, a job that includes managing Ben Taub and its sister facility, Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital. Porsa was almost immediately overwhelmed. “Early on, one of the things I noticed was that Ben Taub and LBJ were taking care of a much higher proportion of Covid patients compared to the rest of the hospitals,” he says when we speak in August. “These are safety-net hospitals, and the indigent, underinsured, and racial minorities also happen to be the segment of the population that is most impacted by Covid.”

In April and May, Houston saw 200 to 400 new cases a day. By mid-June the number was up to 2,000. So many Ben Taub employees caught the virus that the Harris Health System transferred in an extra 200 nurses to fill the breach. The hospital transformed the ER from an open bay to a maze of plexiglass and plastic sheets designed to create negative pressure zones, which allow outside air in while preventing potentially contaminated inside air from escaping. “I can tell my staff are worn out and having anxiety wondering if they’re going to become infected or bring it home,” Porsa says. “When I see nurses with Band-Aids on the bridge of their nose”—from prolonged mask-wearing—“that’s not normal.”

Under ordinary circumstances Ben Taub could transfer its overflow patients to other hospitals, but that soon became challenging. Even the parts of the gargantuan 9,200-bed Texas Medical Center that could handle Covid cases were filling up. “That was a really uncomfortable situation,” Porsa says. “You had patients in the ER waiting for a bed for over 24 hours.”

As case numbers mounted, he got scared. “People are just lined up in the ER, and you hear horror stories,” Porsa recalls. He trails off, looking distressed, before regaining his composure. “You can’t plan for that.”

Another stop, on a gusty Saturday, is the Sunny Flea Market, located in a poor part of Houston’s north side that became a virus hot spot. The market is near a busy intersection bounded by used-car dealerships, a Family Dollar, and the Cathedral of Saint Matthew.

I find Armando Walle, a 42-year-old Democratic state representative, standing near the entrance to a warren of stalls, beside a woman selling Mexican candies from a cart. He’s trying to hand out masks from a big reusable shopping bag jammed full of boxes. Everyone is rushing inside, looking to escape the threatening tropical storm cloud billowing up above us. Their faces are almost all covered, unlike the revelers’ at Flava, with even the kids wearing mini-masks. Undaunted, Walle heads inside, past plates of sizzling pork rinds and rows of python-skin cowboy boots. The shoppers look to be about 98% masked up. He finally finds one target looking for grilled corn, another trailing a pack of hyper grandchildren, and another none-too-discreetly hissing “micas micas micas”—slang for IDs that allow border crossing—as we pass by.

Walle grew up in his district, which is 83% Hispanic. More than half of its population doesn’t have a high school diploma; about a quarter works in construction. It has one of the lowest voter turnouts in the state, according to Walle. After 12 years in office, he’s running unopposed for reelection in November. He says most of his constituents work service jobs and live paycheck to paycheck, and so were unable to stay home during the worst of the outbreak. “Either you put food on the table or you don’t, so someone is risking their life,” he says.

In April, Walle was named Covid relief and recovery czar by the county judge, Lina Hidalgo. “We live in Houston, Texas, with the world-renowned Texas Medical Center,” he later tells me. “And you can go 2 or 3 miles in each direction of the Med Center and find ZIP codes where people can’t see a doctor because they make too much for Medicaid and too little to afford private health insurance.” Those are the families he says he’s trying to fight for. “This pandemic has put a huge spotlight on Texas’ inability to respond.”

Ironically, perhaps no one has been more frustrated by the response than the person responsible for it in Harris County: Hidalgo, the county judge. When I meet her at her downtown office on yet another scorching weekday afternoon, I see why she’s often likened to Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Like AOC, Hidalgo is a twentysomething Latina first-termer; she’s also stirred up similar passions among supporters and critics. Several times during my rounds of Houston, I’ve heard people trash her. Usually it’s just grumbling—who-does-she-think-she-is kind of stuff. A right-wing retired oil executive calls her a “storm trooper.” A woman at my doctor’s office calls her a “loon.” Others say she doesn’t know what she’s doing, that she’s out to get local businesses, that she’s a puppet for the national Democratic Party.

A beneficial side effect of her high profile is that almost every Houstonian now knows what a county judge is and what she does. Harris County is governed by four elected county commissioners and the county judge, an elected, nonjudicial position. The judge presides over the commissioners’ court and is the de facto chief financial officer of the county’s $4 billion budget. She oversees, among other things, tax rates, bond elections, county jails, and storm preparation. She’s also the county’s crisis director, as head of the Harris County Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Management.

Hidalgo arrived in Houston from Bogotá when she was 15. After graduating from Stanford, she worked as an interpreter at the Texas Med Center, then studied law and public policy at New York University and Harvard. She was motivated to enter politics by Donald Trump’s election in 2016. She had no experience, but after Hurricane Harvey hit the following year, displacing more than 30,000 people, many voters started rethinking who they wanted in charge of emergency management. That helped Hidalgo pull off an upset in 2018, when she defeated longtime Republican incumbent Ed Emmett by 1.6% of the vote. She’s now a rising star nationally, appearing on the cover of Time and in a video at the 2020 Democratic National Convention.

Sitting in her office, dressed in a blazer, with her face framed by dark curls, Hidalgo is almost unnervingly soft-spoken, even when discussing heated topics. “I know what we need to do here, but my authority has been stripped away,” she says, spacing out her words with pensive pauses. Her job as emergency manager, she asserts, has been fundamentally undermined by the governor.

When Governor Greg Abbott issued a stay-at-home order on March 31, he and Hidalgo were in accord. “In the beginning we were working together. We were all putting out a fire,” she says. “When the mask order was issued, that’s when it started getting political.” She’s referring to a directive requiring Harris County residents to cover up in public that she signed on April 22, prompting the ire of some of Abbott’s fellow Texas Republicans. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick called the move “the ultimate government overreach,” and U.S. Representative Dan Crenshaw warned of encroaching “tyranny.”

Five days later, Abbott, who didn’t respond to interview requests for this story, barred cities from levying penalties to enforce mask orders. He also said that his stay-at-home order would expire at the end of the month and announced that a phased economic reopening would begin as soon as May 18. Abbott concluded his prepared remarks with a phrase that would return to haunt him as the crisis wore on: “We are Texans. We got this.”

With Abbott’s stay-at-home order set to expire, Hidalgo issued one of her own on May 2. The governor overruled her, saying she lacked the authority. When she tried to issue another one as cases surged in late June, he again said the authority was his and he wouldn’t be exercising it. The best Hidalgo could do was to send an emergency cellphone notification telling citizens the region was in “red alert” and everyone should stay home. After that, anytime she wanted to do something, “it was ‘Pretty please,’ ” she says, stretching out her palms as though begging.

Meanwhile, Abbott’s phased reopening proved scattershot. At first bars were permitted to open at 50% capacity and restaurants at 75%. But near the end of June, he shut down the bars and restricted restaurants to 50% occupancy. That was how businesses such as Flava and officials like Kennedy ended up with an SAT problem on their hands.

Abbott later expressed regret for moving too hastily to reopen bars, but that didn’t stop him from intervening again in September when Hidalgo signed a joint order with Mayor Turner to delay in-person learning in local schools. Abbott rejected that move, too, saying in a statement that school reopenings were up to school boards, which “can base their decisions on advice and recommendations by public health authorities but are not bound by those recommendations.” As the academic year begins, each Houston-area school district is moving forward with a different plan: some virtual, some in person; some now, some later.

“The government needs to tell you when something is dangerous,” Hidalgo says. “But there’s just been huge confusion.”

One consequence of this confusion is that everyone has been left to rely on her own judgment about what is safe—which more or less means no one is safe. As I tour Houston, I find country dance spots such as Wild West and Neon Boots closed until further notice. But closer to the Med Center and across the freeway from Beyoncé’s childhood home, the Turkey Leg Hut has a line out the door. The Rockets’ playoff push is jamming in patrons at the Eastside sports bar Bombshells. And the downtown poolside nightclub Clé is so packed at 1 a.m. that I decide it wouldn’t be safe to go in even with my N95 on. Working my way down the line outside, I ask a group of maskless women why they’re risking it. Kim, a 22-year-old in a leopard-print minidress, tells me, “Ain’t no different from the gas station. Ain’t no different from Walmart.”

The motivations are clearer down on Galveston Island, Houston’s beach retreat, a straight shot out of downtown on Interstate 45 past the Inner and Outer Loops. One Sunday along the Strand, Galveston’s historic shopping avenue, a 59-year-old woman named Maribel Castillo is drinking a Shiner beer with a girlfriend outside a shop selling kitschy beach bags. “I really think they’re stupid, and quote me on that,” she says, holding forth on mask rules and other coronavirus regulations. She’s on the island “doing my part” to help keep businesses open by shopping. “I’m not a Trumpist, but I do think this is political. It will be over when the election is over,” she says, cocking an eyebrow as she raises the bottle for another sip.

A couple of minutes away, the wide, hard-packed beach is busy, with families clustered beneath sports-team-themed canopies and young people gathering in the open beds of pickup trucks driven to the water’s edge. Paul Lucero, a father of three, identifies himself as a Trump-voting Republican. Nobody in his family is wearing a mask. “I think if you want to put yourself at risk, you should go ahead,” he says. “The mask order is just the government covering its own ass.” He smirks and looks me up and down. “No one is wearing one out here except you.”

It’s true—I’ll go home later with tan lines from my N95 straps stenciled across my cheeks. There are worse fates. At one point I see a young woman packing up her things, looking a bit agitated. She identifies herself as Avery Lawson, an IBC (Islander by Choice) rather than a BOI (Born on the Island), and tells me she works as a funeral director. Pointing down the busy beach, she says, “This is the problem. We appreciate tourism, that’s how we make our money, but there is recklessness going on. It’s like there’s no rules, and it’s kind of scary.

“A lot of people don’t see it directly,” she adds. But she does—business is up.

“Everybody is being a dick,” she says and leaves.

Back on the north side of the city, not far from Walle’s district, a line of cars winds through a massive parking lot out onto a freeway feeder road. The lot is normally for two huge event spaces, Stampede and Escapade, but in times of crisis it’s repurposed. After Harvey struck, it became a clothing donation location. This morning it’s a drive-thru food bank. Sirus Ferdows, the venues’ co-owner, is sweating through his shirt with a bottle of water in his hand, overseeing a remarkably smooth operation. Harvey was like a dry run for this catastrophe, he says. Ferdows and his partners have offered their lot for several Thursdays now. Borden Dairy Co. and DiMare Fresh have donated milk and produce, and forklifts will be unloading trucks for the next few hours.

Many people will wait longer than an hour. By the end of the day, more than 2,000 drivers will have been served a box of food—potatoes, apples, beans, and 2 gallons of milk, all swiftly deposited into their trunk by masked student volunteers. I ask Ferdows how much each box is worth, and soon we’re on our phones looking up the cost of a 5-pound bag of onions at local supermarkets. We calculate that the total value is $31 per car.

The vehicles are mostly late-model Corollas, minivans, and F-150s. “People were living a certain lifestyle, and that came to a stop,” Ferdows says, still counting apples. “Now they lost their job, and the car payments that were paused for a couple months are due again.” He shakes his head and almost shouts: “Everybody had a job before! Unemployment was at like 4%!” Indeed, in February, Houston’s unemployment rate was 3.9%; it swelled to 14.3% in April and settled back to 9.4% in July. The Greater Houston Partnership, a local chamber of commerce, estimates that at least 258,000 jobs have been lost since Covid hit. Ferdows says his two event spaces have gone from about 200 employees to none.

I weave through the cars on foot, tapping at windows with notebook in hand. Many of the drivers speak only Spanish; often they’re women, some with kids in the back. Others are men, alone. I soon find that Covid isn’t most people’s main concern at the moment: It’s work and, more pressingly, food.

One of the men, Faustino—who like pretty much everyone will provide only his first name—works at a machine shop welding equipment for offshore oil production. His hours have been cut in half since March, “and now I just need any help,” he says. He’s still wearing grease-stained navy blue coveralls with his name in a white oval on his chest. “My job depends on oil, so when it is cheap, we don’t have work.” West Texas Intermediate crude prices collapsed from more than $60 a barrel in January to less than $12 in April before rising back to about $40 over the summer. Faustino is thinking about doing construction work instead, like most of his neighbors, but for now he’s helping his wife teach their kids in his free time and waiting for the price of oil to bounce back.

“We need food,” Evelyn says candidly. She’s 16, riding in the passenger seat of a minivan, speaking for herself and her mom, who’s from Mexico and too nervous to say anything, Evelyn says, because she doesn’t have papers. “We only have cans, and now we’re having beans twice a day sometimes, and that’s all.” Her dad was laid off from his job in the meat section of a supermarket. “I’m the one who speaks English best, so now I will focus on finding a job to support us,” she says. When I ask if she’s worried about contracting the virus while job hunting, she smiles and shrugs.

Norma, who’s 51, has eight people at home. She says of her husband, “He’s trying to find work.” He used to install air conditioning units for businesses and homes but was laid off and now works only occasionally. They met in El Salvador as teenagers and came to Houston 20 years ago. “With it being so hot now, we thought he would have plenty of work,” she says. “But we can’t pay the bill for the air conditioning of our house. Even the air conditioner man is suffering in Houston.”

At the end of August, a more familiar form of disaster threatens: Hurricane Laura gathers over the Gulf of Mexico, her intensity ratcheting up swiftly and ominously from Category 2 to 3 to 4. Then, seemingly at the last minute, the storm turns north, sparing Houston but destroying other lives not so far away.

Relief from the pandemic seems at hand, too. In September the Med Center reports that the city’s positive test rate is at 7.8%, still above the target ceiling of 5% but much better than August’s 23%. The promising trends have Abbott initiating a new reopening—something local officials fear will amount to another attempt to pretend the danger isn’t really there. “The Governor is about to embark on the same course again,” Mayor Turner warns in a statement before Labor Day weekend. “The State is about to repeat its mistake, expecting a different outcome.”

Near the end of September, another deluge comes. Tropical Storm Beta drops 10 inches of rain. More homes flood, more cars drift away. Covid cases start rising again at Ben Taub. Crisis is brewing from every direction, and we’re as ready as we ever were. It’s as Hidalgo says: “We’re right on the edge of disaster. It’s almost become our way of business.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.