Historic New York Barns Are Ending Up in Japan and New Zealand

Historic New York Barns Are Ending Up in Japan and New Zealand

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Last winter, Ken Zinssar and his brother were working on a car in a wing of the old barn they’d turned into a weekend auto shop. Suddenly, they heard a loud bang, and the structure was beginning to shake.

A main corner post of the barn, which was built around 1780 in New York’s upstate Schoharie County, had snapped. Zinssar and his wife, Doreen, realized they couldn’t keep the place up, so they called Heritage Restorations and said they were ready to sell. “There’s a little pang, but it’s going to collapse otherwise,” Ken says. Doreen adds: “We’re excited to see it go have a new life.”

Since 1997, Heritage Restorations has moved and redesigned about 400 barns, for as much as $5 million apiece. Often it’s just the interiors of the barn that can be reused, as the exteriors are too weathered or incomplete. Many come from New York’s Catskill Mountains region, where porches sag from grand old homes not far from scrap yards with names like Hubcap Heaven. In the 18th and into the 19th century, the Schoharie Valley boasted some of the richest dairy- and farmland in the colonies. Then the Erie Canal opened, shifting American agriculture farther west. Instead of crops, the old infrastructure was left to grow moss.

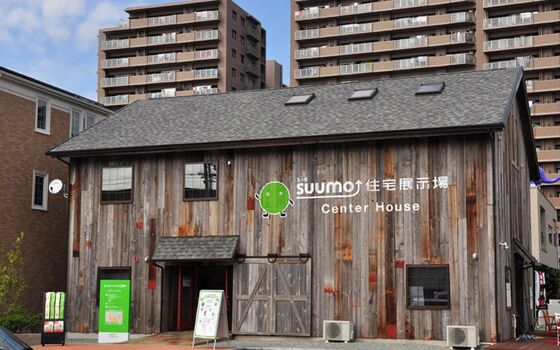

These days the valley, and a surrounding swath of upstate New York and New Jersey, is producing treasure again: Its derelict old barns are finding second lives as star getaways, ranch houses, or wedding venues. Hundreds of these centuries-old outbuildings are being dismantled and set up again, entirely reimagined in places as far away as New Zealand and Japan.

Rustic is in. Old wood is hot. A DIY Network show, Barnwood Builders, has run for eight seasons. But it’s Heritage founder Kevin Durkin who’s responsible for many American barns’ highest-profile moves. “We live in such a tumultuous world—socially, economically, politically,” he says. “When you wake up in the morning and there are 300-year-old beams overhead, it gives you a sense of stability.”

Durkin, a trim 66-year-old, has the long face and patrician manner of John Kerry. But one of his clients—and a cycling buddy—is Kerry’s onetime opponent, George W. Bush. In 2009, Heritage took a chestnut English barn frame built in 1750 from Middletown, N.Y., and topped it with a corrugated metal roof and siding for its future as a guesthouse on the Bushes’ Crawford ranch.

Durkin grew up Catholic in an old New Jersey family. He loved skiing at his parents’ vacation home in the Catskills and digging for arrowheads and old coins in the woods. By early adulthood he was born again as a nondenominational Christian and quit graduate school, where he had been doing research at a pathology lab.

He eventually moved to Texas and opened a workshop for antique wooden furniture reproductions. At one point in the late ’90s, when it needed a showroom, Durkin thought to build it from wood salvaged from an historic barn. One shopper was enchanted by the space and inquired about how to get a house with a similar open-beamed feel. A barn business was born.

Today, Durkin runs the company with millennial-age business partners Matt Brandstadt and Caleb Tittley. It grosses $2.5 million annually and is profitable—but not a fortune maker. Heritage pays barn owners in the low five figures for their structures, purchasing many on spec with the hopes of finding a future client. The dismantling itself costs about $20,000, Durkin says. Beyond shipping, labor, and design, expenses include hiring the Cornell Tree Ring Lab to precisely date a barn based on a wood sample.

Once moved, the structures are frequently modified creatively, like when Heritage built a glassy, luxurious pool house from the bones of a simple toolshed in Sharon, Conn. Another project, outside St. Louis, combined six outbuildings to create a 14,000-square-foot home, with a single bedroom. Occasionally the barns are used on actual farms, as for the supermarket-wine Gallo family, who commissioned a restoration in California for their horses.

Late-night host Jimmy Fallon had a relatively modern barn on his getaway estate in the Hamptons but wanted something more impressive. The existing structure was supported by 6-by-6-inch beams, so Durkin’s team found a heavy Canadian barn of the same size but with 12-by-12-inch elm beams to undertake a tricky barn-within-a-barn rebuild—tearing down the old frame at the same time they erected the new one. They also left room to place a tree indoors, in the middle of the barn, winding a spiral staircase around it with spindles and rails made from the branches.

Most barns get cleaned out, taken apart, and shipped to the company’s workshop in Big Timber, Mont., where a team of eight craftsmen fumigates and reconditions every beam. They ship every labeled piece together to their destination, where they’re reassembled into something new. The exterior wood is often sold for other projects—most clients are looking for a rustic interior, not a leaky old shell. Insulation is hidden in the new structures, and roofs are added of copper, metal, slate, tile, or thatch. Even with shipping, which Durkin figures would happen for new construction, too, he considers the work sustainable, calling it “the ultimate recycling.”

Like Durkin, buyers gravitate toward the grand 18th century Dutch barns that tend to come from New York and New Jersey. From the outside, they’re tall and peak-roofed, with bends in the roofline on each side where livestock stalls were placed. Step into one, with its impressive 30-foot-high central nave and side aisles, and you might have the feeling of entering a church. It isn’t coincidental: Many Dutch barns were built on a basilica-style plan.

Walking through the Zinssars’ barn before the deconstruction begins, Durkin points out the design details. “You’d stack sheaves of grain up here,” he says, signaling the rafters with a laser pointer. “But when this is emptied out, it’s like a cathedral.”

That day, local laborers Steve Swift, Brandi Swift, and Tyler Nark were cleaning piles of abandoned detritus that showed how time had lapsed: lawn mowers, tractor parts, bicycles, carriage harnesses. “I’ve got the world record for taking down the most Dutch barns,” says Steve, who dismantled his first in 1981. “It’ll never be broken, because there aren’t that many left.” An estimated 700 barns in this style remain. Durkin started out finding them by “literally beating the bush, getting chased by dogs,” he says. These days he and Swift cruise Google Earth and post “We Buy Barns” signs at intersections.

Not everyone cheerleads the work. Preservationist Greg Huber of Eastern Barn Consultants avoids mentioning Durkin by name, referring instead to “a so-called person who moves barns to Texas.” A Pennsylvania-based former biologist and tree lover turned historian and barn expert, Huber visited 610 barns before editing the latest edition of the book The New World Dutch Barn: The Evolution, Forms, and Structure of a Disappearing Icon.

“They have a soul and an aura,” Huber says. “If you’re going to take a barn out of its historic context, it would be good to [save records] so that information is not lost forever.”

Durkin argues that moving barns beats leaving them to rot. “They belong in place, they belong local—but they don’t belong in the landfill,” he says. “We’re the next best thing.”

How To Take Down and Rebuild a Barn

- Clean out building.

- Document everything with photographs and measurements. Number the beams.

- Starting at the peak, peel roof off.

- Take down rafters.

- Carefully strip off exterior siding.

- Lift off the “plates”—or longest 40-to-50-foot beams that cap the wall posts—by unpegging them.

- Take down the “bents”—wall beams—that frame the barn.

- Pry up and save the floor, including the “sills”—the heavy beams underneath.

- Ship all materials on a flatbed truck to a workshop.

- Wash the wood.

- Replace or repair any missing or damaged parts with matching period wood.

- Recut any missing joints and test-assemble them.

- Fumigate all materials against insects.

- Ship the materials to be rebuilt in their new home.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.