GM Learns How to Navigate Trump’s Washington

GM Learns How to Navigate Trump’s Washington

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Corporate management in the age of Donald Trump is a learning experience. Perhaps no company has absorbed more painful lessons than General Motors.

GM’s political education by fire started just over a year ago, when the profitable automaker announced plans to shut down several factories, including in Michigan and Lordstown, Ohio, part of a once-Democratic county that went for Trump in 2016. The backlash was swift and fierce, from both parties. The president savaged GM and Chief Executive Officer Mary Barra for days, declaring in one tweet that “The U.S. saved General Motors, and this is the THANKS we get!” Democrat Sherrod Brown, Ohio’s senior senator, called the plans “corporate greed at its worst.”

It has taken a year, plenty of nasty tweets and a 40-day labor strike, but the iconic American industrial giant is finally discovering how to navigate the capital under a mercurial and unpredictable president whose policies have pressured the auto industry on several fronts. The company has little room for error, when neither the Twitter-loving president nor the Democratic Party wants to see their voters lose jobs.

So GM overhauled its Washington lobbying crew. It scrambled to create a future for plants once slated for closure. And after months of reluctance, GM sided with the president in his battle to wrest control of auto-efficiency standards from California. That move drew something unthinkable 12 months ago — thanks from Trump.

GM had found itself in a shooting gallery last November for doing what pre-bankruptcy GM was slow to do: Barra was cutting jobs to maximize profit and investing in green technology to get a jump on clean-air rules.

And that was the problem. Creating a profitable U.S. auto industry that aggressively promoted clean cars was very much a Barack Obama mission, not a Donald Trump one. The new president had promised to protect manufacturing jobs, particularly in states expected to be critical in the 2020 presidential campaign. For GM, closing plants in Michigan and Ohio was not a good look. Even before the flap over GM’s big restructuring, Trump had chastised it for making a compact hatchback in Mexico instead of Lordstown.

Today, GM concedes it made mistakes in how it presented the plant closings, especially by failing to make it clear that total U.S. factory jobs didn’t decline because positions at idled facilities were being shifted to other plants. “We need to communicate our commitment to the United States and to our communities in a proactive manner—and not just say it, but demonstrate it and continue that work,” says Everett Eissenstat, senior vice president of public policy at GM. “We can always do a better job with that, and we will remain committed to do a better job.”

The trickier task will be sticking to a long-term strategy that Barra has deemed central to GM’s survival, even as the administration keeps the pressure on. Peter Navarro, director of the White House’s Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, put it bluntly in an interview: GM and other U.S. multinational companies must change their culture “in deference to a buy American, hire American president.”

The call from the radio station came early on the Monday after Thanksgiving last year. Michigan Representative Debbie Dingell couldn’t believe it at first: The reporter told her GM was planning to close two factories in her home state.

A former GM executive before being elected to Congress as a Democrat in 2014, Dingell didn’t think the automaker even had the legal authority to shutter plants in the middle of a contract with the United Auto Workers. The company hadn’t given much of a heads-up to anyone in Washington before it made it official in a press release. And the devastating news leaked before GM told the affected workers.

To Dingell, the episode illustrated the company’s struggle to operate in Trump’s Washington. “I don’t think they realized that a president could cause as much pain as he did after the announcement of those four closings,” says Dingell, whose late husband, John, was the auto industry’s biggest ally in Congress for decades. “I don’t think that they understood what the consequences would be.”

To David Green, then the president of UAW Local 1112 in Lordstown, GM’s move was “like a shot in the gut.”

Sitting in Lordstown’s mostly deserted union hall last July, with yard signs for the “Drive it Home” campaign to save the plant still stacked near the reception area, Green says some employees can’t or don’t want to uproot — and should’ve been told all along that their jobs in Lordstown were in jeopardy. “Being a good corporate citizen doesn’t mean you come in and shutter communities at the drop of a hat,” says Green, who has since transferred to a GM facility in Indiana. “Do it with some dignity and foresight, and I don’t think they would be as hated.”

GM has ceased production at plants in Ohio, Maryland and Michigan already, and a factory in Ontario will follow by the end of this year. That list includes the Chevrolet Cruze in Lordstown as part of a realignment that will cut excess production and use more resources for electric and self-driving vehicles. The moves threatened some 14,000 salaried and factory jobs. GM has offered transfers to most of the 2,800 UAW workers whose jobs are being eliminated and will retool a plant in Detroit to make electric trucks and SUVs, but it didn’t say so at the time of the announcement.

The company’s initial attempt to give Lordstown workers some hope only worsened suspicions. In May, Barra told Trump in a telephone call that the company was in talks to sell the Ohio car plant to an affiliate of Workhorse Group Inc., a tiny electric truck maker.

Skeptics immediately questioned whether Loveland, Ohio-based Workhorse had the financial wherewithal to acquire the plant and bring back thousands of workers. The buyer that was announced last month is a startup called Lordstown Motors Corp., which plans to use intellectual property from Workhorse to make electric pickups. After a fresh round of criticism, GM on Monday said it would loan Lordstown Motors $40 million to get its project off the ground while the company seeks cash.

That announcement came just days after GM and its battery partner, South Korea’s LG Chem Ltd., said they would jointly invest $2.3 billion in a new electric-vehicle battery plant to be built elsewhere in Lordstown. But while the factory would employ 1,100 workers, the pay would be significantly less than the $32-an-hour top wage that GM assembly workers receive.

The new battery plant won’t appease the former GM workers or the auto-workers union in the Youngstown region, says William Binning, a former Republican Party chairman in Mahoning County and an emeritus political science professor at Youngstown State University. That would seem to be a political liability for Trump.

Shortly after the announcement about the Lordstown closing, Binning predicted Trump’s reelection bid in Ohio would take a hit—particularly after the president visited Youngstown, near Lordstown, in 2017 and declared the jobs are “all coming back.” Trump added: “Let me tell you folks in Ohio and this area—don’t sell your house.”

And yet, today, Binning says GM bungled the situation so badly that while workers and some voters are angry that Trump didn’t keep his campaign promises to save the jobs, many appear to blame the automaker more. “The degree of animus is much greater towards the company than it is towards Trump,” he says.

For all its political potency, the question of where GM employs its workers is less important to its financial future than the rules dictating what it can sell. And in that area, too, the company has struggled to navigate the Trump era. On his first Tuesday in office, Trump summoned Barra and her counterparts at Ford Motor Co. and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV to the White House. He wanted them to hire more workers, a decision he said he’d make easier by rolling back regulations.

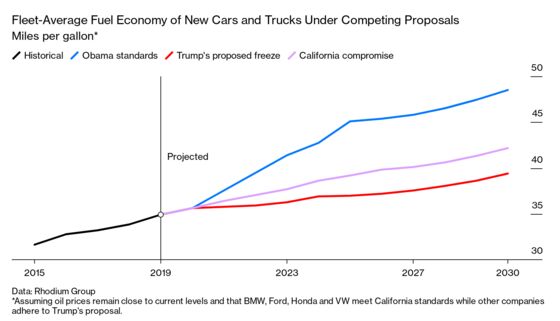

Less than two weeks earlier, Obama’s EPA had locked in rules that aimed to bring the fleet-average of new cars to roughly 50 miles per gallon by 2025. Barra and her fellow CEOs urged the new president to reexamine the rules and stressed the need for standards to be uniform nationwide, something they’ve consistently pushed for since. Automakers and their trade associations later pressed that case in a series of letters to the administration, casting the Obama decision as a political response to Trump’s victory that unfairly truncated the review the companies had been promised.

The standards were quickly looking more daunting amid surging sales of less-efficient SUVs and soft demand for zero-emission electric cars. The companies hoped a further review would relax the tougher standards, but they stopped short of asking that the rules be thrown out entirely. GM had already invested billions to meet the Obama-era rules and had too many plants already. In effect, the companies wanted help, so long as it wasn’t overly disruptive to them.

It was a nuanced pitch to a president who had campaigned on a pledge to slash regulations that, in his view, stifled business, especially manufacturing jobs in the American heartland. It was also a miscalculation.

More than a year later, in August 2018, Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Transportation went far beyond what GM and other companies wanted: The administration proposed freezing fuel-efficiency requirements after 2020 and stripping California’s authority to regulate tailpipe greenhouse gas emissions, which the state has done in conjunction with federal agencies since 2011 in the name of nationwide uniformity.

In response, GM called for a national electric-car sales mandate and other incentives for carmakers. “We know that the industry can do better than that,” GM President Mark Reuss told reporters in October 2018. The concept struck Trump administration officials and lobbyists from rival carmakers as tone deaf: It would effectively nationalize California’s mandate to promote zero-emission vehicle sales, which the Trump administration had pegged for elimination.

In June, GM joined 16 other automakers in publicly urging Trump to reach a deal with California. They warned that a failure to do so could lead to “an extended period of litigation and instability, which could prove as untenable as the current program.”

But Trump administration officials have shown no interest in a détente with the state. They’ve argued that the rollback of regulations will cut auto prices and spur sales, putting more consumers into newer, safer cars that are also cleaner—claims that experts dispute.

GM and other automakers have largely failed to mount a pro-consumer narrative of their own, says Mike McKenna, a longtime energy lobbyist and supporter of Trump’s policies who met with GM about the emissions rules while serving on Trump’s presidential transition team.

“These car companies never figured out that it’s not about them,” McKenna said in an August interview, before he joined the White House as a deputy assistant to the president. “I think they thought, ‘Well, you should be doing this because we’re asking for it.’”

While Trump’s agencies are still finalizing new federal standards, automakers are choosing sides. In July, Ford, Honda Motor Co., BMW AG, and Volkswagen AG hitched their fortunes to California by agreeing to voluntarily reduce greenhouse gas emissions 3.7% per year after 2020, a rate between Trump’s proposed freeze and what the Obama-era targets demanded.

After the Trump administration formally moved in September to bar California from regulating tailpipe greenhouse gas emissions, California and several other states sued to protect its authority to set its own standards—precisely the scenario GM and other automakers had tried to avoid.

In late October, GM—the company that had helped lead the industry’s courtship of Trump for measured relief during his first days in office—formally sided with him to revoke California’s clean-car authority.

On Sept. 5, Barra returned to Washington for a rare face-to-face meeting with Trump. While few details have emerged about that discussion, news broke the following day that the Justice Department had launched an investigation into whether Ford, Honda, BMW, and VW’s emissions deal with California ran afoul of antitrust laws.

Legal experts immediately wondered aloud if the probe was in retaliation for the companies’ backing of California’s compromise emissions targets. The Justice Department has rejected the suggestion that politics played a role in the decision.

Whatever the motivation, the department’s move was a milestone that symbolized how much GM’s position in Trump’s Washington had changed.

After Barra’s meeting with Trump, the company began working with the White House’s Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy on a longer-term plan for its Lordstown factory, says Navarro, the office’s director. The initiative aims to ensure that Lordstown Motors is successful while also building out the electric vehicle manufacturing operation quickly and finding alternative uses for unused portions of the factory to further boost jobs, he says. “I think it’s fair to say that GM mishandled the Lordstown issue and that GM has had a reputation of offshoring American jobs,” Navarro says. “But I think it’s also fair to say that GM is well aware of those issues and has redoubled its commitment.”

GM also has hired new lobbyists. One key personnel move came in August 2018, when GM brought in Eissenstat, a former Trump economic adviser, to lead its lobbying globally. He reports directly to Barra.

Weeks after the furor over factory closures erupted in November 2018, GM added Ballard Partners to its roster of Washington lobbying firms to represent it on fuel economy and manufacturing issues. Brian Ballard, the firm’s founder, was one of Trump’s top fundraisers in the 2016 election. And the company added a number of in-house lobbyists who had previously worked for Republicans in Congress. Senior officials in the office with ties to the Obama administration no longer work at the company.

The shift began to show in GM’s messaging. Last March, Barra credited Trump’s renegotiated free-trade deal with Canada and Mexico for pushing GM to invest $300 million in its plant in Lake Orion, Mich., where it will add 400 jobs to produce a new electric vehicle originally slated to be made overseas.

And Barra’s early September sit-down with the president may have marked a turning point.

She gave no details after the meeting, only calling it a “productive and valuable discussion” before being whisked away in a gray GMC Yukon. But the next day, Larry Kudlow, Trump’s economic adviser, said Barra had expressed support for the president’s fuel-economy plan. Later, after GM sided with Trump in the courtroom battles over California’s authority, the president did something he hasn’t done before: He thanked GM for standing with his administration.

But Navarro made it apparent that GM isn’t in the clear yet with Trump’s White House, and much hinges on what happens next in Lordstown.

He says the question for the administration remains “whether GM will follow through on its commitment to this mission.”

Like the moves that got GM in trouble in the first place, the company’s commitment will be at the mercy of the market. If its electric vehicles don't sell, it might be tough to make the huge Lordstown battery plant a success. If they do, GM can win back friends in Ohio and Washington.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Flynn McRoberts at fmcroberts1@bloomberg.net, Dimitra Kessenides

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.