Giuliani Keeps the Hustle Going, Even as Trump Is Impeached

Giuliani Keeps the Hustle Going, Even as Trump Is Impeached

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Rudy Giuliani is answering his phone less these days. For years the former New York mayor was renowned for talking with any reporter who could get hold of his number, but now he’s more likely to respond by text or call back with his lawyer on the line, if he responds at all. When I first called Giuliani in February for a Bloomberg Businessweek story on his foreign business dealings in Ukraine and beyond, he told me he had five minutes but spoke for closer to 45. That happened twice. By May, when I was reporting on a trip he was planning to Kyiv to push for investigations to help President Donald Trump, he refused to comment, texting: “Why would I call you after your extremely unfair article. Talking to you was a waste of time.” Later that month, he butt dialed me, as he has other reporters, and I overheard him apparently having a heated argument with an unidentified woman. “I really don't care,” he texted when asked about the episode. I’ve spoken to him a few times since May, but Giuliani declined to comment for this story.

He’s on television less, too, perhaps because his appearances in defense of Trump, for whom he’s serving as an unpaid personal attorney, haven’t always been helpful. (In September, as the impeachment inquiry was launched, Giuliani appeared on Fox News and shouted “Shut up, moron! Shut up!” at a fellow guest.) That’s not to suggest he’s backing off. In addition to his roles as lawyer, adviser, pundit, and shadow diplomat, he’s now trying his hand at journalism, if you can call it that. In early December he announced he was working with One America News Network, a right-wing U.S. cable channel, on a project attacking the impeachment inquiry. The series focuses on the debunked conspiracy theory that it was Ukraine, not Russia, that meddled in the 2016 U.S. election and on unproven allegations that former Vice President Joe Biden engaged in corruption by calling for the ouster of a prosecutor investigating Burisma Holdings, a gas company for which Biden’s son, Hunter, served as a board member. Ukrainian officials have said there was no active probe of Burisma at the time.

Undeterred by the hearings in Washington, at which he was invoked countless times, Giuliani flew to Ukraine in December to interview so-called “witnesses” to “testify under oath” about his unsubstantiated claims of Ukrainian interference and the Biden family’s alleged corruption. (No one was under oath; these were just TV interviews.) Several former prosecutors who once worked with Giuliani have noted he’s getting “evidence” from the kinds of people he might have been investigating in his heyday as a U.S. attorney in the 1980s.

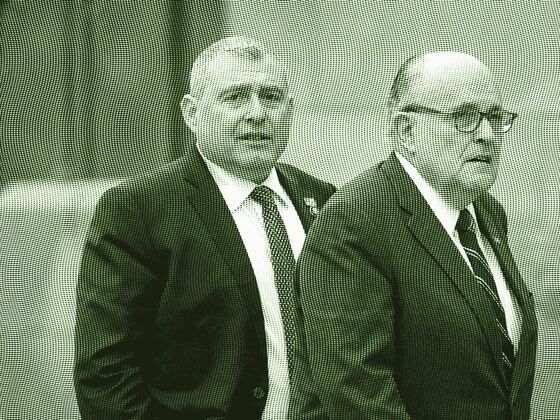

Roughly 18 months ago, Giuliani’s world was gate-crashed by Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, two Soviet-born emigres who were seen everywhere with “America’s Mayor” before being arrested for campaign-finance violations in October. Giuliani’s back-channeling to Ukrainian officials with Parnas and Fruman on behalf of Trump has landed him in legal jeopardy. Federal prosecutors are looking at his business dealings and whether he violated foreign lobbying laws. Parnas and Fruman have both pleaded not guilty. Giuliani denies any wrongdoing.

Besides Parnas and Fruman and a motley crew of former Ukrainian prosecutors, there are more, previously unreported characters in Giuliani’s universe—including a Congolese-born former NFL player trying to drum up business for him in Africa. Giuliani is never so busy, no matter how hot things get for his No. 1 client, that he can’t explore new opportunities.

The broad outlines of his business have been reported by Bloomberg and other news organizations. But the flow of money still remains largely unknown, and the details could determine whether he faces serious legal peril. Giuliani recently settled a bitter divorce battle that revealed not only how much he’s amassed over the past two decades—$30 million in assets—but also how much he and his now-ex-wife spent: $230,000 a month. The divorce fight tied up his bank accounts and forced him to borrow from friends to pay his taxes earlier this year, he told reporters this summer.

This week, Giuliani returned to the limelight with his customary gusto. His client was on the verge of becoming only the third president in history to be impeached by the House of Representatives. And so Giuliani was again everywhere at once, dialing up some of the very assertions that plunged Trump’s presidency into crisis by affirming he’d told Trump that the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine, Marie Yovanovitch, was in the way. He was back in his element.

Some friends say Giuliani has always cared more about being a power player than making money. Even if that’s true, the need to be on the stage doesn’t make the need for money go away. He could have been a man of influence. He could have continued to make millions. The compulsion to do both might be his greatest vulnerability.

Much of Giuliani’s reputation as the prosecutor who took down the Mafia stems from his astute sense of public relations when he took over as U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York in 1983. Instead of having a secretary announce indictments, as his predecessors did, Giuliani hired three people just to handle the media, and he became a star. “I remember walking into the U.S. attorney’s office one day, and he had a press conference on,” recalls Nick Akerman, who worked with Giuliani in the office and is now a partner at Dorsey & Whitney in New York. “It looked like the West Wing of the White House, there were so many people in there.”

The America’s Mayor title was courtesy of Oprah Winfrey, who’d been impressed, as so many were, by his leadership following the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. After finishing his term as mayor in 2001, Giuliani went on to make millions giving speeches and consulting on security around the world. He found national and local government clients in more than 30 countries, from Brazil to Colombia to Qatar. He started multiple companies—the biggest were Giuliani Partners, Giuliani Security & Safety, and Giuliani Capital Advisors—and advised clients on bankruptcy, security, and policing strategy.

But he was aiming higher, and had been even before his term as mayor was over. An aborted run for the U.S. Senate against Hillary Clinton in 2000 gave him a thirst for the national stage. He withdrew from that race in May 2000 amid personal turmoil, announcing within the space of a few weeks that he had prostate cancer and that he was splitting from his wife, Donna Hanover, after reports he was having an affair with Judith Nathan. Nathan would go on to become his third and now ex-wife.

It was that first run that planted the seeds of his network of political and business allies in Texas. One of the most important figures in his circle is Roy Bailey, a Republican fundraiser and Texas insurance mogul. Giuliani met Bailey in 1999 and encouraged him to run for the Senate. After the campaign was abandoned, Bailey became managing partner of Giuliani Partners. Bailey would go on to introduce Giuliani to a string of energy executives in Texas. In 2005 he helped him land a lucrative position as senior partner at a major Houston law firm, Bracewell & Patterson, which was then renamed Bracewell & Giuliani. By 2006, as Republicans in Texas were looking for a successor to President George W. Bush, Bailey thought Giuliani might be their man. He connected him to the late T. Boone Pickens, the legendary oilman and prodigious political donor, says Jay Rosser, a former Pickens aide. Pickens became Giuliani’s key fundraiser after the two met to discuss his candidacy in 2006.

At the time of his run, Giuliani held progressive views in favor of gun control, gay rights, and abortion rights. To soothe the Bible Belt voters who were uneasy with the candidate, former Texas Republican Congressman Pete Sessions—a close ally of Bailey, who financed, and frequently ran, Sessions’s campaigns—often accompanied Giuliani at public events. (Sessions is one of several Texans who achieved some notoriety in the impeachment inquiry, having written a letter last year to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo urging the removal of Yovanovitch, whom he said was disparaging Trump. The congressional spotlight was even brighter on Rick Perry, the former Texas governor and Trump’s first secretary of energy. Perry was described as one of the “three amigos,” along with Gordon Sondland, U.S. ambassador to the European Union, and U.S. Special Representative for Ukraine Kurt Volker, who were pushing Giuliani’s irregular diplomacy efforts in Ukraine.)

With powerful Lone Star State backers and Bailey’s connections, Giuliani raised more money in Texas than anyone else in the race by the end of 2007. But his campaign was dogged by his refusal to sever his financial ties to his consulting firm if he became president or disclose his client list on the campaign trail. “I’m an owner,” he told NBC’s Meet the Press in 2007. “I’m not going to do more than what is absolutely required.”

Unlike Trump, who managed to brush off similar criticism, Giuliani flopped at the ballot box. And so he returned to making money. In 2012, Darwin Deason, a billionaire Republican donor based in Dallas, joined Giuliani in an investment firm they named Giuliani Deason Capital Interests LLC.

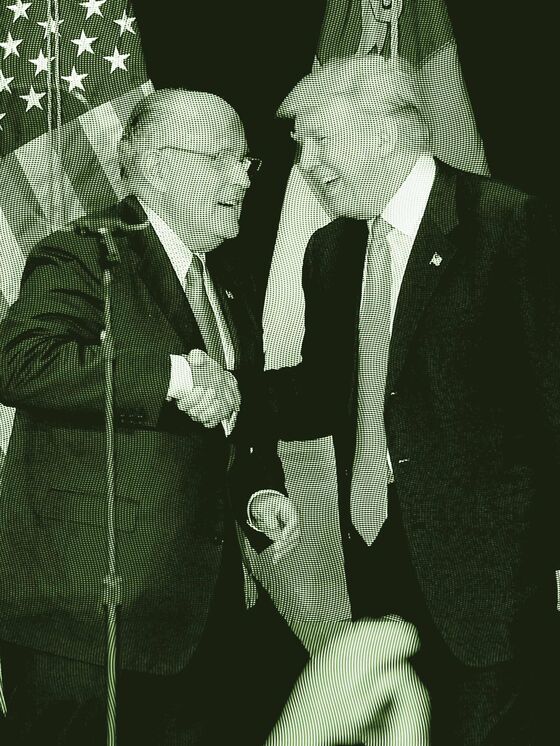

Giuliani was a particularly effective surrogate for Trump during the campaign. Many believe his hint on Fox News that then-FBI Director James Comey was planning something big on Hillary Clinton prompted Comey to publicly announce he was reopening the investigation into Clinton’s use of a private email server. The announcement is widely regarded as a turning point in the race. When Trump won the election, Giuliani expected to be rewarded. Trump offered him a handful of positions, but not the one he really wanted: secretary of state. Many in Washington said his international business relationships might make it difficult for him to win confirmation in the Senate. But Giuliani told me earlier this year it was his then-wife Nathan who prevented him from taking the post, because she didn’t want him to take a pay cut. In 2017, Giuliani earned $9.5 million, according to divorce proceedings. He gave up at least $4 million a year when he stepped down from his former law firm, Greenberg Traurig, to work for Trump for free in 2018.

Instead, he went on to become a kind of shadow secretary of state, traveling the world first as Trump’s cybersecurity adviser and then as his personal lawyer. It may have been a better position, given his needs, than the one that eluded him. He could be the crucial man, the insider who knew what the president wanted and was committed to providing it. And he could continue to make a lot of money. “He’s really trading on his relationship with Trump,” says Akerman, Giuliani’s former associate in the U.S. attorney’s office. “That's where he’s making his money. He’s combining the two things. Everybody knows he’s the personal lawyer to Donald Trump, so if you want to buy influence with the administration, you hire Rudy Giuliani. That’s his M.O.”

Giuliani has steadfastly denied he trades on his connections to Trump or engages in influence peddling on behalf of his private clients. “I don’t ask the president for anything for them ever,” he told me earlier this year. “Any contract I have makes it clear I don’t lobby the government.” That doesn’t mean he hasn’t brought up clients with Trump. During a 2017 meeting in the Oval Office, Trump asked then Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to drop a criminal case against an Iranian-Turkish gold trader named Reza Zarrab, who was Giuliani’s client. Tillerson refused, but Trump told him to talk to Giuliani about the case. The New York Times later reported that Giuliani attended a separate Oval Office meeting to press Trump and Tillerson about the case. In October, Giuliani told me at first he didn’t bring up Zarrab with Trump but then said he might have done so. “Suppose I did talk to Trump about it—so what?” he said.

In 2017, Giuliani went twice to Ukraine, once for a consulting gig and the other time for a public speech, and both times he met with President Petro Poroshenko and top members of his government. When I spoke to Giuliani in February and March of this year, he grew testy when asked about those meetings. “I fail to see how this has to do with President Trump,” he grumbled. Little did I know that in the same time frame, Parnas and Fruman were meeting with Poroshenko and then-Prosecutor General Yuri Lutsenko to push Giuliani’s plan to help Trump via investigations into the Bidens and alleged Ukrainian interference in the 2016 election. The meeting was first reported by the Wall Street Journal last month.

As for Giuliani’s consulting work in Ukraine, it’s still unclear who paid him. He said earlier this year that a local businessman named Pavel Fuks and an unspecified number of other “private individuals” paid him for the security consulting contract he had with the eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv. Fuks confirmed the arrangement but declined to provide more details. It remains unclear if those private individuals have any relationship to ongoing probes.

Giuliani met Parnas and Fruman in the summer of 2018. They’d been looking for a way to get to the former New York mayor to recruit him to a company, Fraud Guarantee, that Parnas was trying to start with a man named David Correia. They described the company to contacts as an investor due-diligence company that could prevent the next Bernie Madoff-like scandal.

Parnas and Fruman wanted Giuliani to star in infomercials about Fraud Guarantee, similar to a low-budget ad campaign Giuliani did in 2013 for the identity theft company LifeLock Inc. He met with Parnas and Fruman in New York in July 2018 to discuss the company. Giuliani was advised not to do it because of regulatory risks and a feeling the company wasn’t ready to go, people familiar with the situation say.

He went ahead anyway. In September, Giuliani agreed to work on the venture in exchange for as much as $2 million in fees and a small equity stake, according to the Wall Street Journal. Not long after, Parnas and Fruman raised $500,000 for Fraud Guarantee from a Long Island lawyer named Charles Gucciardo. He paid the funds directly to Giuliani Partners. Gucciardo declined to comment for this story, but his lawyer said he thought he was investing in a company backed by America’s Mayor.

“Mr. Giuliani was going to do for the Company what he did for LifeLock,” Randy Zelin, a lawyer for Gucciardo, said in a statement. He said his client was a passive investor in a company that he believed had “tremendous potential” in light of promises that Giuliani “was going to be behind, alongside of, and in front of the company.” Fraud Guarantee still has a website, but there’s no evidence it’s had any customers.

Giuliani continued to juggle paid gigs with his shadow diplomacy efforts. In December he traveled to Bahrain to pitch for a security-consulting contract. While there, he met with King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa, and the two discussed “Bahraini-U.S.” relations, according to the Bahrain News agency, which described Giuliani as the leader of a “high-level U.S. delegation.” In January he, Parnas, and Fruman held a Skype call with a former Ukrainian prosecutor general, Viktor Shokin, who told them about alleged corruption by the Bidens. A few days later, Giuliani met with Shokin’s successor, Lutsenko, in New York. The next month they met again in Warsaw. Giuliani’s choice of partners in Ukraine was opportunistic at best. Shokin and Lutsenko have themselves faced allegations of corruption, which they have denied. During their combined four years as prosecutor general, Ukraine’s equivalent of U.S. attorney general, Shokin and Lutsenko never prosecuted any high-level officials for corruption, despite Ukraine being ranked as one of the most corrupt countries in the world.

Giuliani has accepted Lutsenko and Shokin’s often wild allegations without much probing. During his recent trip to Ukraine, Shokin told Giuliani that his medical records show “he was poisoned, died twice, and was revived,” a claim Giuliani made to his 610,000 Twitter followers. Shokin’s alleged poisoning has never been reported in Ukraine.

Giuliani, Parnas, and Fruman became almost inseparable after the Fraud Guarantee deal, friends say. In late May, Giuliani celebrated his 75th birthday with a party inside the owner’s box at Yankee Stadium with about 40 friends, most of whom he’d known for years—a mix of Fox News presenters and Republican lawyers and businessmen from New York and Texas. Parnas, dressed in an unbuttoned Yankees jersey and wearing a gold chain, and Fruman, with his graying hair slicked back, worked the room as some of Giuliani’s old friends looked on warily.

As he sought new business ventures that spring, Giuliani was working with Eric Beach, a California lobbyist who co-headed the pro-Trump Great America political action committee in 2016 and had worked on Giuliani’s presidential bid in 2008. Beach said in an interview that he introduced Giuliani in the spring to a couple named Patrice Majondo-Mwamba and Debbie Smith to talk about drumming up clients who could hire Giuliani for security work in Africa. Like Parnas and Fruman, this couple is far removed from Giuliani’s universe. Majondo-Mwamba is a former NFL player born in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Beach said there was no formal arrangement in place between Giuliani and the pair, and he’s not aware that anything materialized from their contact. “They did a call and had a meeting with the mayor,” Beach said. “They were suggesting some countries had security needs that would fit within the Giuliani security business.”

In September, Majondo-Mwamba and Smith were making the rounds at events held on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly in New York, trying to tee up meetings for Giuliani to land security contracts. At a cocktail reception for visiting dignitaries, they approached a U.S. businessman with links to wealthy Africans with a brazen pitch: Help get us a meeting for Giuliani with a prominent African businessman, and he can influence where Trump goes on his first visit to Africa. Majondo-Mwamba introduced himself as the head of Giuliani’s security company in Africa. He declined to comment for this story.

“They really wanted African businessmen to meet with Rudy to discuss where Air Force One would land in Africa,” the American businessman recalled. “They kept saying, ‘We have clearance from Oval.’” The businessman said he declined to make any introductions but asked what would be in it for wealthy businessmen to meet Giuliani. “It’s their chance to influence U.S. foreign policy,” they told him.

Beach said such bragging was routine. “I don’t think that’s surprising,” he said. “I have been in tons of meetings where people say they’re close to Trump and to Rudy.” Meanwhile, Beach said he’s been in discussions with Giuliani about raising a private equity fund to invest in cybersecurity and other unspecified ventures. He said the venture still hasn’t been finalized.

Over the summer, Giuliani tried to find more contacts in Ukraine to pursue the investigations he thought would benefit Trump. Dimitry Firtash, a Ukrainian oligarch fighting extradition to the U.S. on bribery charges, began working to dig up dirt on Biden over the summer in an effort to get Giuliani’s help in his case. The Justice Department has described Firtash as an associate of Russian organized crime. He has denied all the charges. Two pro-Trump lawyers close to Giuliani, Joe diGenova and Victoria Toensing, took over Firtash’s case, using Parnas as a translator. Prosecutors in New York have said that a lawyer for Firtash transferred $1 million from a Russian bank into the account of Parnas’s wife in September, raising new questions about who Parnas was working for as he hobnobbed with Giuliani. A spokesman for Firtash said Firtash had no knowledge of the transfer. Parnas has maintained it was a loan.

The cash from Firtash, who made his fortune in Ukraine’s gas industry, puts Parnas and Fruman’s other efforts to make money in a new light. Using Giuliani’s name to open doors around the world, they’d been hustling for months to try to do a deal to sell gas to Poland and Ukraine. They lined up meetings with executives from Ukraine's state-controlled Naftogaz and high-powered Republicans with ties to Giuliani's old Texas connections.

Giuliani continued to make money on the side to finance his work in Ukraine on behalf of the U.S. president. In July he traveled to Albania to speak at a Free Iran summit and meet with the leaders of National Council of Resistance of Iran at the organization’s camp outside the capital, Tirana. NCRI, which the State Department designated as a terrorist organization until 2012, has provided a consistent source of income for Giuliani, who’s given paid speeches around the world for the group since 2008. Senate Democrats have complained to the Justice Department twice about his failure to register as a foreign agent for that work and other international clients.

Not long after his trip to Albania, Giuliani was in Madrid with Parnas at his side. On the morning of Aug. 2, Giuliani met with Andriy Yermak, a key adviser to Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zelenskiy, at the Westin Palace Hotel, a five-star hotel in the center of the city. As they drank coffee in the hotel lobby, Yermak noticed a group of people who were clearly with Giuliani sitting at a nearby table. It was only later, when Parnas and Fruman were arrested and their pictures were everywhere, that Yermak realized one of the men with Giuliani that day had been Parnas, he recalled in a recent interview in Kyiv.

Yermak says he spoke with Giuliani for an hour and a half and they bonded over a common friend—Vitali Klitschko, a former boxer and now the Kyiv mayor, whom Giuliani has known since advising Klitschko on his first, unsuccessful mayoral campaign in 2008. Giuliani pressed Yermak on what he knew about Burisma and Ukraine’s alleged meddling in the 2016 U.S. election. Yermak replied that he knew very little about either. Over the next few weeks, Giuliani worked through Volker and others to try to persuade Yermak to draft a statement for Zelenskiy to announce investigations. The announcement was never made.

On the same trip, Giuliani sent out a mysterious tweet featuring four random pictures that appeared to show him wandering in the woods, with the comment: “South of Madrid are beautiful small towns and lovely countryside and very wonderful people.” It turns out he was in Spain to meet with another previously undisclosed client, Alejandro Betancourt Lopez, a Venezuelan energy executive, at Betancourt’s estate outside Madrid, the Washington Post was first to report. Betancourt is under investigation as part of a $1.2 billion federal money laundering case. A month later, Giuliani and Betancourt’s other lawyers met with the head of the Justice Department’s criminal division to argue that their client shouldn’t be charged. Jon Sale, one of the lawyers, said his client denies any wrongdoing and declined to comment further.

Last week, Giuliani was back at the White House. As impeachment dominated the attention of Washington and prosecutors dug around in his finances, he was briefing the president on his recent trip to Kyiv. —With David Kocieniewski, Christian Berthelsen, Erik Larson, and Greg Farrell

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Ferrara at dferrara5@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.