Germany Pays Workers to Stay Home to Avoid Mass Layoffs

Germany Pays Workers to Stay Home to Avoid Mass Layoffs

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Kaluza + Schmid GmbH, a company in Berlin that helps organize trade fairs, corporate retreats, and other events, was having a good year. Managing director Ruediger Koch says his schedule was so full that he had to turn away business. Then, toward the end of February, as governments in Germany and elsewhere began stepping up efforts to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus, cancellations began rolling in. In the space of a few days, the 80-person outfit lost some 30 projects worth €1.6 million ($1.8 million)—roughly a sixth of its yearly sales.

Koch made a choice unimaginable to most managers in America: Instead of firing his employees, he sent them home and kept paying them. The entrepreneur availed himself of a state-funded program called Kurzarbeit, which translates into short-time work. Dating back to the period following World War II in Germany, it’s designed to help companies weather difficult times without having to resort to mass layoffs, disruptive to businesses and the larger economy. “We would have had to let go pretty much everyone if it weren’t for short-time work,” Koch says. “Now we’re able to hold on to our people and their know-how.”

Kurzarbeit typically covers 60% of lost wages (67% for people with children). Companies are still responsible for paying workers and must apply to get reimbursed by the government. That’s far more generous than what furloughed workers are entitled to in the U.S., where employees typically go without pay but retain access to such benefits as health insurance and life insurance.

While labor codes in Europe are often described as a brake on economic growth because they prevent companies from hiring and firing at will, as they’re able to do in the U.S., the current pandemic has revealed the virtues of programs such as Germany’s. Several other nations on the continent, including France, Italy, and the Netherlands, also allow distressed companies to tap government funds to pay salaries in periods when they have little or no income. Many have recently pledged to bolster those programs with additional funds.

At least 26 U.S. states have what’s known as shared-work programs that operate on similar principles. But take-up has been more modest than in Europe, as several of the state-run programs are of more recent vintage and therefore less well known. Also, company eligibility is contingent on employees working fewer hours rather than no hours at all, as is possible in Germany.

“Short-time work allows companies to weather crises that aren’t their fault and restart operations very quickly with the same personnel once things improve,” says Markus Helfen, a human resources researcher at Berlin’s Free University. “It’s a model universally lauded by scientists that has proven itself in the past.”

Traditionally, the main beneficiaries of Kurzarbeit have been manufacturers, which have tapped the program during production dry spells or larger economic disruptions such as the global financial crisis. This time, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government is urging companies in service industries—hit especially hard by forced closures and other government measures adopted to slow the spread of the virus—to avail themselves of the scheme. Officials have also loosened rules on how much of a company’s workforce must be affected before it can apply for wage subsidies.

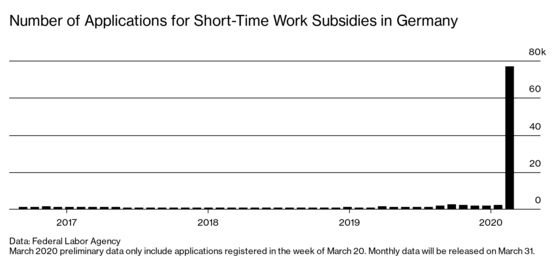

A total of 1.5 million German workers went on short-time work in 2009. Officials in Merkel’s government estimate the number will reach at least 2.15 million this year, at a cost of approximately €10 billion. The wave is already building: Some 76,700 companies applied for short-time work in the week ending March 20, up from a weekly average of 600 last year, when the country’s industry was struggling because of global trade tensions, according to figures from the Federal Labor Office.

Volkswagen AG, which has been shuttering plants across Europe, plans to place about 80,000 employees in Germany on short-time work, while rival Daimler AG is reducing hours for most of its 170,000 staff in Germany beginning on April 6. Sports apparel maker Puma SE introduced short-term work for 1,400 employees, and Deutsche Bank has said it’s considering idling some staff.

Germany’s system isn’t without downsides. Verdi, a labor union for the service sector, says the government subsidy isn’t large enough to help workers in low-wage industries such as hospitality and restaurants. Some small-business owners are also critical of the policy. Sam Kamran, who runs five eateries and cafes in Frankfurt that employ about 140 people, says he can’t afford to wait days or weeks for government reimbursements because restaurateurs have significant personnel costs every month. “You can’t simply pay that from savings,” Kamran said in a video posted on YouTube.

Despite such shortcomings, the program is expected to stave off a big jump in joblessness in Germany. If the Merkel administration is successful in expanding short-time work benefits to the service sector, small businesses, and freelancers, “then we might only see a relatively small increase in unemployment,” says Alexander Herzog-Stein of Germany’s IMK Institute for Macroeconomics and Economic Research.

Kaluza + Schmid’s headquarters in Berlin sit mostly empty, except for Koch and a skeleton crew of five employees, some of whom are responsible for making sure that suppliers and part-time workers continue to get paid. “We can handle that for a few months, but of course not indefinitely,” he says. “The shorter this shutdown, the better business will be afterward.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.