Germany’s Industrial Giants Confront Their Mortality on Election Eve

Germany’s Industrial Giants Confront Their Mortality on Election Eve

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Klaus Rosenfeld was making a routine visit to a potential supplier in the fall of 2018 when, unexpectedly, a big opportunity presented itself. Executives at the company let it slip that it was about to be sold. The terms hadn’t been finalized, and Rosenfeld’s Schaeffler AG could cut in if it acted fast.

On the drive home to Frankfurt, Rosenfeld called Georg Schaeffler, the son of one of the company’s founders and now its chairman and main shareholder, to brief him. Before hanging up, the two men agreed to sleep on it. Less than 12 hours later, Rosenfeld had the green light to make a bid for Elmotec Statomat, a world-leading supplier of equipment used in the manufacture of electric vehicles. “We’ve never turned around a deal so fast,” says Schaeffler’s chief executive officer. “It was clear the technology would accelerate our transformation—a small step with a big impact.”

Impulse buying runs against the grain of German capitalism, which is more measured and methodical than the U.S. version. Yet in boardrooms from the Black Forest to the Baltic coast, a sense of urgency is taking hold with the realization that the German economic model is reaching its limits: Precision machining bits of metal down to micron levels of tolerance and assembling them into cars and other complex mechanical systems that are then shipped to all corners of the globe can no longer guarantee affluence for the country’s 83 million people.

Germany’s auto industry has been on the back foot since the 2015 emissions-cheating scandal involving Volkswagen AG, and it faces an existential threat from the looming extinction of the internal combustion engine. Yet Europe’s largest economy is ill-equipped to make the transition into cleaner, digital technologies. The country’s carbon dioxide emissions are the sixth-largest in the world, and it ranks 30th in mobile broadband speeds, with download rates less than half as fast as in China.

Even a success such as BioNTech SE’s development of one of the leading Covid-19 vaccines is tempered by the fact that the Mainz-based biotech needed Pfizer Inc. to bring the shot to the world. Then there’s the sensational collapse last year of electronic-payments company Wirecard AG, which was seen as a rare homegrown digital champion before being outed as Germany’s biggest postwar fraud.

The Sept. 26 election, which will mark the end of Angela Merkel’s 16-year tenure as chancellor, adds to the collective sense of unease. Her successor, whoever he or she may be, will inherit a nation that’s reliant on the U.S. for security, China for growth, and the European Union for clout. Finding Germany’s place in the world while guiding an economic makeover will be a monumental task.

Central to that effort will be building on Germany’s manufacturing prowess, which was on full display at Schaeffler’s headquarters in Herzogenaurach, a hamlet in northern Bavaria, when Bloomberg Businessweek visited this summer. Inside one of the plants, the air is filled with the smell of lubricants and the clang of machines pounding metal bands into precisely contoured rings that will be fashioned into bearings. The friction-reducing parts are the company’s mainstay, ranging from thumbnail-size ones found in car transmissions that sell for less than €1 ($1.18) apiece to others for wind turbines that are so big you could drive a van through them and cost upwards of €100,000 each.

Every pass through a metal press adds a new detail in a process that’s been engineered over decades to minimize the need for humans, as indicated by the presence of just a handful of technicians. An old press dating from the 1950s—little bigger than a stand-up piano—is positioned prominently on the factory floor. It’s a monument to the company’s humble beginning as a maker of handcarts, a cheap and convenient conveyance for everything from rubble to coal to hay in a battered Germany emerging from the ruins of World War II.

Schaeffler’s management isn’t overly sentimental about the past, even though relatives of its founders still control the company. Elsewhere on the campus, a building that once housed a paper plant is set to be bulldozed to make way for an €80 million lab, where it will carry out research and development in traditional fields like materials science as well as new ones, such as artificial intelligence and electrochemistry. The company’s evolving ambitions are visible on a line that churns out axles embedded with motors and other components for electric cars from Audi AG and Porsche AG. The complex in Herzogenaurach will also house a center dedicated to accelerating development of components for hydrogen-powered vehicles, which many regard as the industry’s next frontier.

“You need to be optimistic about the future to make it in business,” says Georg Schaeffler, 56, who as a child could see the lights of the factory from his bedroom window across the Aurach river. “If my father and my uncle had the confidence to start a company right after World War II, then we can be successful in this current transformation.”

Georg’s father invented and patented the caged needle-roller bearing—essentially small rods held steady in metal casings. The component found its way into the axles, rotors, and transmissions of cars manufactured by VW, Mercedes-Benz, and BMW. When German carmakers began opening plants abroad, Schaeffler tagged along. Today the business has operations in 50 countries and more than 80,000 employees. Every day it molds about 7,000 tons of steel—roughly the amount of metal used to build the Eiffel Tower. Sales of auto components contributed three-quarters of the €12.6 billion in revenue it booked in 2020.

Although it’s a global enterprise with shares listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, Schaeffler remains a prototypically German business: family-owned, tradition-bound, export-driven, and focused on factory floors rather than shop windows or the internet. It, along with much of German industry, faces a reckoning. Based on the various targets announced by governments from China to the U.K., battery-powered vehicles will outsell those with combustion engines within a decade.

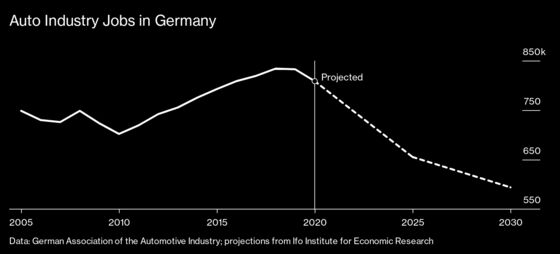

To barrel down the autobahn, a Tesla still needs bearings. But Schaeffler also makes clutches, transmissions, and other components that will be mothballed or at least marginalized in the migration to electric vehicles. The shift will eliminate at least 215,000 jobs across Germany’s auto industry by 2030, about a quarter of the sector’s workforce, according to forecasts by the country’s auto lobby. To weather the transition, the company will need to replace about €6.8 billion in revenue.

Rosenfeld and Georg speak almost daily—sometimes from across the Atlantic. Georg often rises at 3 a.m. to participate in board meetings from his home in Texas, where he’s lived for decades after seeking to chart his own course outside the comfortable confines of the family business.

To future-proof Schaeffler, the two men are spearheading a plan to sell or close some units—the company recently unloaded one that makes sprockets and other chain-drive components for combustion engines—while milking others for cash to invest in new endeavors. “There’s still a long way to go,” says Rosenfeld. “The challenge is to harvest the foundation businesses and grow the new business, both at the right pace.”

Some of the seeds he and Georg planted are starting to put forth shoots. New products include metal sheets coated with nanomaterials to conduct current in fuel cells, electric steering systems for autonomous vehicles, as well as plug-and-play sensors backed by cloud-based software that monitors and predicts breakdowns on assembly lines. “We want to be one of the winners of this transition,” Rosenfeld says. “But there will be casualties,” he adds.

Many of the giants of Germany Inc. are also overhauling themselves to remain relevant. Daimler AG is moving ahead with a separate listing for its truck unit. Siemens AG, the giant industrial conglomerate, is breaking itself into smaller, more agile entities. VW is undertaking a €73 billion transformation to put software and batteries at the heart of its vehicles.

Corporate transformations can be perilous, as Georg Schaeffler well knows. In 2008 the company—which even then knew it needed to expand beyond mechanical components—made a disastrously timed bid for Continental AG, a larger German auto parts maker that had just acquired electronics businesses from Siemens. The aim of the tender offer was to secure a sizable minority so as to have a say over company strategy. But with the financial crisis playing out in the background, investors jumped at what was intended as a lowball bid, and Schaeffler ended up with 90% of Continental’s shares.

So as Merkel was battling to prevent the euro from collapsing under the weight of accumulated government deficits in Greece, Portugal, and Spain, Schaeffler found itself contending with its own debt crisis—a hangover from the tender offer. Georg, who’d been pursuing a career in corporate law in the U.S., was sucked back into the day-to-day affairs of the family business, which since his father’s death in 1996 had been run by hired hands. Rosenfeld, a former banker, was brought in to clean up the mess. He restructured some €11 billion of debt, partly by paring back the Continental stake. Then in 2015 he managed a public offering of nonvoting shares that raised €938 million, with Georg and his mother, Maria-Elisabeth, retaining full control of the business.

After teetering on the brink of collapse, Schaeffler has developed a willingness to make tough choices—maybe more so than some of its peers in German industry. Last September it announced plans to sell or close several plants in Germany and cut 4,400 jobs in Europe by the end of 2022, about 8% of its workforce in the region.

Current trends are promising. In the first half of 2021, Schaeffler’s e-mobility business, the umbrella for all its EV endeavors, secured €2.1 billion in orders, already meeting its full-year target. Operating margins rebounded from last year’s pandemic hit, and the company raised its cash-flow target by one-third to at least €400 million.

“It’s critical that we get the mindset right,” says Georg over dinner in Herzogenaurach in a rare interview, adding that the company needs to “stay positive and confident, because culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

As the company pushes ahead with its revamp, its leaders look to Berlin with a degree of trepidation. They fret about the security and cost of energy as Germany phases out coal and nuclear power, about underinvestment in digital and physical infrastructure, and about red tape that bogs down projects such as a new Tesla Inc. factory outside Berlin. Schaeffler, along with much of German industry, also fears it will get caught in the middle of U.S.-China tensions.

It’s difficult to see how a government with the vision and focus needed to overcome such challenges will emerge from the September vote. With loyalties fragmented among six parties, a messy three-way coalition will almost certainly be needed to secure a majority in parliament, which presages policy gridlock. That’s the last thing German business needs, according to Rosenfeld. “This is a global competition,” he says. “From Berlin we need a more pragmatic can-do attitude.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.