Welcome to the Age of One-Shot Miracle Cures That Can Cost Millions

Welcome to the Age of One-Shot Miracle Cures That Can Cost Millions

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Omarion Jordan spent almost all of his first year of life in hospital isolation rooms. The nightmare began with what looked at first like diaper rash, a string of red marks that quickly spread across his body when he was just shy of 3 months old. Creams and ointments failed, as did the eczema shampoo treatment an emergency room doctor prescribed. Last July, hours after Omarion’s pediatrician injected his three-month vaccines into his thighs, the boy’s scalp began weeping a green pus that hardened and peeled off, taking his wispy brown curls with it. His head kept crusting over, cracking, and bleeding, and his mom, Kristin Simpson, started to panic. “His cries sounded terrible,” she recalls. “I thought I was going to lose him.”

She took her son back to the ER two nights in a row, only to have the doctors send them home each time to their apartment in Kendallville, Ind. “They thought I was some antivaccination person,” she says. “They looked at me like I had a foil hat on my head.” The next day, however, the boy’s pediatrician diagnosed pneumonia and sent them back to the hospital for a third time, at which point they got more attention. A battery of tests revealed a rare genetic disorder called severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome (SCID), better known as the “bubble boy” disease, which makes 40 to 100 American newborns each year extremely vulnerable to infections, like John Travolta in the old TV movie. Omarion, transferred to an Ohio hospital three hours away, was confined to an isolation room with special air filters.

Left untreated, SCID kills most children before they turn 2. Simpson spent five months waiting for a bone marrow transplant for her son, the only conventional treatment and one that the doctors told her carried serious risks. Then they told her about an alternative: an experimental gene therapy that just might cure Omarion outright. “It was kind of like a leap of faith,” she says, but she figured that if it didn’t work, they could go back to praying for the transplant.

It worked. In April, Omarion was released from the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, where a team of researchers had taken stem cells from his bone marrow, bathed them in trillions of viral particles engineered to carry the gene missing from SCID patients, and reimplanted them in the boy to begin replicating, repairing the errors encoded in his cells. A preservative in the cell treatment left him smelling like creamed corn for days afterward, Simpson says, but his immune system has begun working normally, his white blood cell count rising like those of the other nine kids in his study. Bloomberg Businessweek watched Simpson and Omarion venture for the first time outside of their St. Jude housing facility to play. Inside what’s known as the Target House, they’d spent months in a filtered, isolated apartment for children with compromised immune systems. “He’s just a healthy baby now,” Simpson says in the house’s Amy Grant Music Room, sponsored by and lined with photos of the Christian pop singer. “It’s definitely a miracle.”

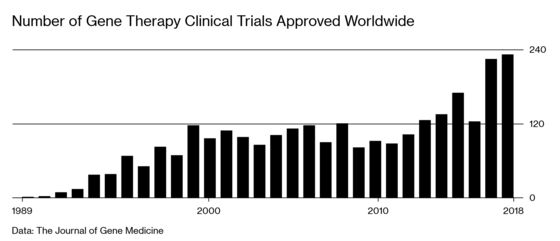

This is the tantalizing promise of gene therapies, the potential cures for dozens of once-incurable illnesses. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued its first approval of a systemic gene therapy, a Novartis AG treatment for spinal muscular atrophy, on May 24 and says it expects to approve 10 to 20 therapies a year starting in 2025. There are more than 800 trials under way, targeting diseases including rare metabolic disorders, sickle cell anemia, hemophilia, and Parkinson’s. As the list grows, such treatments have the potential to fundamentally remake the health-care system at every level.

There are two big caveats. First, most studies haven’t run longer than a few years, so it’s impossible to know yet whether the therapies will remain effective for life, help everyone the same, or yield side effects decades in the future. Only about 150 children have received the Novartis muscle treatment, Zolgensma, and at least two have died, though the therapy doesn’t appear to have been to blame.

The other problem is cost: These treatments are expected to run several million dollars a pop. Zolgensma is the most expensive drug ever approved in the U.S., with a price tag of $2.1 million for a one-time infusion.

“The cures are coming,” says Alexis Thompson, a gene therapy pioneer who heads the hematology department at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, “but there are still a lot of considerations.” Safety, efficacy, fairness, and long-term follow-up care top her list. “Even if someone undergoes gene therapy and is cured of a disease, we need to ensure that they have access to a health-care system that will allow us to follow them for conceivably 10 to 15 years,” she says. Then there are the more ghoulish concerns about returns on investment that tend to come with pricey research and development projects. “While this proposition carries tremendous value for patients and society, it could represent a challenge for genome medicine developers looking for sustained cash flow,” Goldman Sachs analyst Salveen Richter wrote last year in a note to clients titled “Is Curing Patients a Sustainable Business Model?”

Every human has about 20,000 genes, half each from Mom and Dad, that make proteins to break down food, maintain cell health, provide energy, pass signals to the brain, and so on. A defect in a single gene can cause any one of about 7,000 potentially devastating or life-threatening diseases. Viruses have been thought to offer a solution since the 1980s, when an MIT researcher first modified one to deliver a healthy gene into a human cell. In 1990 the National Institutes of Health used such a treatment to save 4-year-old Ashanthi DeSilva from an immune disorder that would otherwise have killed her in a matter of years.

A handful of early disasters temporarily halted progress on gene therapies. In 1999 an overwhelming immune response to one treatment killed an 18-year-old from Arizona, turning his eyes yellow and spiking his fever above 104F. Researchers abandoned a SCID trial in France in 2002 after one of the 10 bubble boys developed leukemia; eventually, four of them did. Still, scientific work continued, and as researchers created better technology, they started delivering remarkable results. In 2007 patients with a genetic form of blindness saw their vision improve. Blood cancer patients given only weeks to live in 2012 went into remission after their immune systems were reprogrammed to attack malignant cells. Hemophiliacs started producing clotting proteins. The past five years have been revolutionary, says Lindsey George, a hematologist who leads gene therapy trials at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “This is a transformative time,” she says. “It isn’t just a hope and a whim. It’s supported by data and significantly so.”

George cautions that it’s tough to identify rare side effects with samples as small as most of the studies so far have used. Part of the problem is the supply of the therapies themselves, which require months of growing, purifying, and testing at manufacturing facilities such as the one at St. Jude. In Memphis, 200 1-milliliter vials of the master cell line used to target SCID sit in a stainless-steel tank of liquid nitrogen 4 feet in diameter, kept at a temperature of -256F. After thawing one of the tubes, technicians covered in sterilized clothes feed and nurture the cells for weeks in enclosed cabinets, moving the treatments from vials to flasks to stacked trays as they grow. Eventually, trillions of particles, tested for months to ensure their potency and safety, can be distilled into treatments for as many as 600 infants with the most severe form of SCID.

St. Jude spent millions of dollars to develop a bank of cells so it can treat new patients in a little more than a week at a cost of tens of thousands of dollars per case. For less practiced facilities, the manufacturing process for each treatment can cost $500,000 or more.

Researchers and doctors want to cure diseases that affect the most people, and the industry is focused on developing those treatments to sell. Novartis says Zolgensma doses are worth more than double the $2.1 million the company is charging. Spark Therapeutics Inc. has set the price for Luxturna, its treatment for an inherited form of blindness, at $425,000 an eye. “We really tried to focus on what is sight worth for a young child or an adult,” says Spark Chief Executive Officer Jeff Marrazzo, “as well as what we needed to charge to be able to reinvest.”

For some patients, gene therapy would be cheaper than current lifelong treatments. Take Tim Sullivan, a 63-year-old computer programmer born with hemophilia. Sullivan’s earliest memories involve lying in a hospital bed, looking up at a bottle of blood slowly dripping essential clotting proteins into his veins. Even though medical advances eventually made it easier to extract the proteins from donated blood, such treatments left Sullivan infected with HIV and hepatitis C, the diseases that killed his two younger brothers, also hemophiliacs. He suffered almost every day with pain that came with even minor bumps and bruises and with inflammation from his weakened joints. “It’s been my life,” he says. “Pain was my constant companion.”

Since birth, Sullivan’s care has cost millions of dollars. He estimates that the drug he used from Pfizer Inc., BeneFix, and a longer-lasting version called Alprolix from Sanofi SA, cost an average of about $300,000 annually. The year he underwent a knee replacement, which required substantially higher doses of the drugs, the bills soared to more than $1 million.

Then, a year ago, Sullivan enrolled in a clinical trial for a gene therapy in development from Spark and Pfizer, and most of his symptoms disappeared, as did his routine drug costs. “It’s life-altering,” he says. “I haven’t had to stick a needle in my arm for a year.”

Sullivan, like Omarion, didn’t have to pay for his experimental treatment. Once the dozens of coming gene therapies are approved and on the market, they may well be unavailable to most Americans, even those with insurance, says Steven Pearson, founder and president of the nonprofit Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, which assesses the value of medicine. “Employers will feel they can’t cover it, especially smaller employers,” he says. “It’s like a freight train running against a brick wall.”

In countries with centralized health coverage, such as the U.K., drugmakers don’t sell their products unless the government agrees to cover them. In the U.S., drug companies sometimes step in to help struggling patients, giving them medications for free or reduced prices, but it’s unclear whether this will be the case for all gene therapies. “As we start getting into diseases with more people, like hemophilia and beta thalassemia, access to care is going to be an issue,” says Harvard medicine professor Jonathan Hoggatt.

Gene therapy developers including Novartis, Spark, and Bluebird Bio Inc. are starting to pitch novel and controversial payment plans. These include annuity models that allow insurers to pay off the treatments over time. So far, the programs aren’t broadly covered by Medicare or Medicaid; developers must negotiate them individually with insurers. “The way the payment system is set up in the United States, we pay by episode of care, and we happen to be delivering a one-time therapy,” says Spark’s Marrazzo. “Ultimately, I think we should get paid a smaller amount, over time, as long as it’s working. We should be standing behind these products.”

Critics argue that longer-term payment plans could just as easily lead to price escalation and abuse. “If we just turn every single treatment into a home mortgage, all we do is kick the can down the road,” Pearson says. “Prices will be too high because they will think we can pay for it later.”

For patients suffering from these kinds of rare diseases, many of which generally prove fatal, there may not be time to resolve all the questions of supply and demand. Some academics are willing to build gene therapies to order, but that means patients need to raise the money themselves. Amber Freed, a former equity analyst in Colorado, is trying to raise $1 million to cover the development costs of a treatment for Maxwell, her 2-year-old son, who suffers from a rare, newly discovered genetic disease. She’s $600,000 short, and he has a year, maybe two, before the worst of the symptoms, severe seizures, may cause permanent damage. “His birthday was so bittersweet,” Freed says. “Time is not on his side.”

The pharmaceutical industry appears confident that gene therapy’s market problems will sort themselves out. The likes of Roche Holding AG and Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. are paying billions or tens of billions of dollars to acquire promising companies. Novartis, too, got access to Zolgensma through its $8.7 billion purchase of a tiny startup that, at the time, had no products on the market.

Still, big hopes are being pinned on small studies with few patients. Sarepta Therapeutics Inc. went all-in on a therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy after it had been tried on only four boys. “For the next 24 months, we’ll be spending many hundreds of millions of dollars to support this,” says CEO Doug Ingram. “We’ll have to build more manufacturing capacity in the next two years than all the gene therapy manufacturing that exists in the world today.”

Ingram says it’s a moral imperative given that 400 boys in the U.S. and 3,000 around the world die from the disease every year. Although the study hasn’t yet been published, he says preliminary findings for the first four patients are unprecedented, with improvement at every time point and across every test. “All the markers would lead one to believe these kids are transformed,” he says.

At home in Indiana, where she lives with Omarion’s father and his family, Simpson still takes many of the same precautions she did when Omarion was suffering from SCID, including wiping down all his toys daily to ward off germs. “I’m still very paranoid,” she says. “I’ll be really overprotective.” But she recognizes how far they’ve come from only a few months ago, when he was stuck in the isolation chamber where he took his first stumbling steps. “He’s started to develop really fast, because he can just crawl anywhere on the ground and play with whatever,” she says.

His favorite activity is chasing a ball around a park near their home. Again and again, he’ll throw it as far as he can, then fast-crawl after it, without having to worry about the germs in the grass or the dirt.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jim Aley at jaley@bloomberg.net, Caroline WinterJeff Muskus

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.