China’s Three-Child Policy Puts More Pressure on Working Women

China’s Three-Child Policy Puts More Pressure on Working Women

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When a marketing director at an internet startup in Beijing told her bosses she was pregnant in 2017, they congratulated her. Then, she says, they began sending her on business trips with increased frequency. After some months they demoted her and hired another person to fill her position. When she had to take sick leave because of complications with her pregnancy, the company refused to pay her salary and removed her from the email system, leaving her little choice but to quit, she says.

Four years on, Liu Tao is still deep in a legal battle with her former employer. That name is a pseudonym she uses to speak about her case, to avoid losing out on future job opportunities or being bullied online, which has happened to other Chinese women who’ve sued their employers for gender discrimination. The ordeal has taken a toll on her finances—driving her to the brink of bankruptcy—and on her mental health: She says she contemplated suicide in January 2018 after a tribunal rejected the first of three labor dispute arbitration requests on the grounds of insufficient evidence. Her son was just 4 days old at the time. “It’s been an excruciating process,” says the 37-year-old, who’s seeking a public apology and 50,000 yuan ($7,728) as compensation for the emotional pain she’s endured. “All I want now is justice,” she says, “and that no more women will have to suffer what I did.”

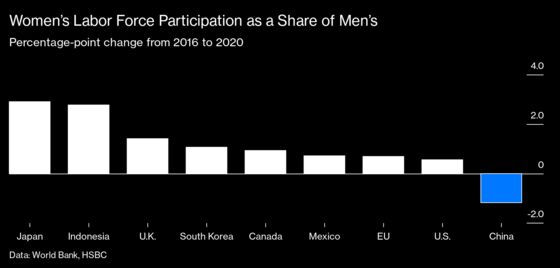

Although there are no official statistics on workplace discrimination in China, interviews with lawyers, recruiters, academics, and labor activists point to a notable pickup in cases of employers declining to give jobs and promotions to women. Economists who analyzed data from a single large city found the gender pay gap for new hires has widened more than 20% since 2013, when the government began allowing some families to have two children. And the ratio of female to male workers has dropped the most among major economies in the past four years, according to data compiled by the World Bank.

It’s a problem policymakers will need to grapple with now that China’s government has eased restrictions further to allow couples to have three children as part of an increasingly desperate effort to reverse falling birthrates. “The three-child policy will certainly be a huge blow to working women,” says Liu Minghui, a law professor at China Women’s University and a public-interest lawyer who’s representing Liu Tao (the women are not related). “Companies already don’t want female workers under the two-child policy—now they are going to discriminate even more.”

China can’t afford to have women dropping out of a workforce that’s already shrinking as its population ages rapidly. The country has one of the highest labor force participation rates for women in all of Asia, at 61%, but that number has been trending down since the 1990s. Raising the rate by 3 percentage points would deliver a $497 billion boost to the economy, equivalent to 2% of gross domestic product, according to a 2019 study by PwC.

A former human resources manager at a Beijing-based internet company says she witnessed the environment for women deteriorate during her five-year stint there. Managers commonly sidelined female employees after they got pregnant, and they pressured one to resign by dispatching her on frequent business trips, says the woman, who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation. “We became less willing to hire female workers after 2016,” she says, referring to the year the one-child policy officially ended. “For positions that required long hours, I didn’t even bother to open the résumés I received from female candidates.”

One of the biggest reasons behind the growing discrimination is employers’ reluctance to pay for maternity leave, according to corporate recruiters. By law, women in China are entitled to at least 98 days of leave with full pay, but the benefit is only partially funded by the state. Also, women are seen as less likely to commit to long working hours after they have children because they lack access to child care. Plus, they shoulder a bigger share of domestic duties, spending an average of 126 minutes on housework a day, compared with 45 minutes for men, a national survey in 2018 showed.

China’s tech industry, the source of many of the country’s most coveted jobs, has become a notoriously unfriendly place for working mothers. “The growing push among the tech companies, most famously, to force workers to work excessively long hours is another trend that disproportionately affects women, because it’s still the women who are expected to do all the housework,” says Geoffrey Crothall, communications director at advocacy group China Labour Bulletin.

China already has laws that ban gender-based discrimination in employment. Nevertheless, the central government felt compelled in 2019 to lay out specific rules related to hiring: Prospective employers may no longer ask female job candidates about their marriage and childbearing status, demand pregnancy tests, or post help wanted ads that specify a gender requirement or preference.

The rules don’t seem to be having much effect. According to a survey of more than 7,500 women released in March by Zhaopin Ltd., an online recruitment firm, as many as 56% had to field intrusive questions in job interviews, and 30% said they encountered employers who only wanted men. Pop Mart International Group Ltd., a Beijing-based toymaker, apologized last month after it came under intense criticism on social media for asking female job candidates to write down whether and when they planned to have children on an application form. “The enforcement of existing laws and regulations is still very poor, and even the government itself is widely discriminatory in its hiring,” says Yaqiu Wang, China researcher at Human Rights Watch. Some 11% of the government job postings for civil servants in 2020 specified a preference or requirement for men, according to a study by the advocacy group.

Few women have taken employers to court for discrimination, because it’s both time-consuming and expensive. Plus, the odds of winning are slim, and the compensation is usually too low to justify the effort. “It’s extremely difficult for women to defend their rights through legal channels, because many judges are not even aware of the problem,” says Guo Jing, an activist who’s set up a hotline to provide free legal help to working women.

In 2014, Guo sued a vocational school in the city of Hangzhou for discriminating against female candidates, because it considered only men for a secretary position. She prevailed and received 2,000 yuan in compensation from the school, becoming the first plaintiff to win a judgment in a gender-discrimination-in-hiring case in China.

In Liu Tao’s case, a Beijing court ruled in favor of the company in December and rejected her appeal earlier this month. The court accepted the company’s argument that each of its actions was a normal business decision and decided there wasn’t enough evidence to prove discriminatory intentions. Nineteen Chinese legal experts wrote a dissenting opinion on the case, saying judges should look at behaviors in a systematic way and avoid taking a too-narrow approach.

Liu Tao is determined to keep fighting and will appeal the latest ruling. “If no one sues companies that discriminate against women, they will only become even worse,” she says. “But if every woman can fight for their rights, surely things will change for the better with time.” —James Mayger and Yujing Liu

Read next: Aging China Relies on ‘Young Old’ to Take Care of Oldest Seniors

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.