The Case of the Empty Frames Remains Art World’s Biggest Mystery

The Case of the Empty Frames Remains Art World’s Biggest Mystery

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On the night of St. Patrick’s Day in 1990, Rick Abath was working the overnight shift as a security guard at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. While the rest of the city drank and partied and drank some more, he and another guard, Randy Hestand, took turns patrolling the empty rooms of what had once been the ostentatious home of a Victorian-era socialite who was really into art.

Their shift started at 11:30. Abath made the first rounds while Hestand hung out at the security desk. They were young, in their mid-20s, and didn’t have any formal security training. Hestand was a New England Conservatory student who liked to use the downtime to practice his trombone. Abath played in a rock band and was known to occasionally show up to work drunk or stoned. He had a scruffy beard and long brown hair that fell in a mess of Weird Al ringlets, and on this particular night he arrived wearing bright red pants and a tie-dyed T-shirt under his unbuttoned security shirt.

The Gardner Museum didn’t have security cameras in its galleries, just motion detectors that recorded Abath’s movement as he made his rounds. At one point, an alarm on the fourth floor went off, but when Abath checked, nothing seemed to be amiss. He finished his tour of the museum around 1 a.m., then switched places at the security desk with Hestand, who went off on his turn to patrol.

Abath was still relaxing behind the desk at 1:24 a.m. when two Boston police officers approached a side entrance and asked to be let in. “I could see that they had hats, coats, badges,” he said in a 2013 interview with a Boston Globe reporter. “So I buzzed them in.” (Abath didn’t respond to emails, Facebook messages, or letters asking for an interview for this story.)

The officers explained that they’d received reports of a disturbance and needed to ask the guards some questions. “Randy, will you please come to the desk?” Abath radioed to Hestand, who quickly returned. That’s when things got weird.

The cops asked Abath for his ID. Then they said they had a warrant for his arrest. They asked him to step out from behind the security desk—taking him away from a panic button installed near it—and to stand against a wall. Then they handcuffed him. “I’m just standing there with my jaw open going, ‘Wow, what’s going on? What did Rick do?’ ” Hestand told the radio station WBUR. They cuffed Hestand, too.

“This is a robbery,” one of the men said. They wrapped the guards’ heads with duct tape, leaving a space for them to breathe, and led them down to the museum’s basement. They handcuffed Hestand to a limestone sink and left Abath slumped on a concrete ledge.

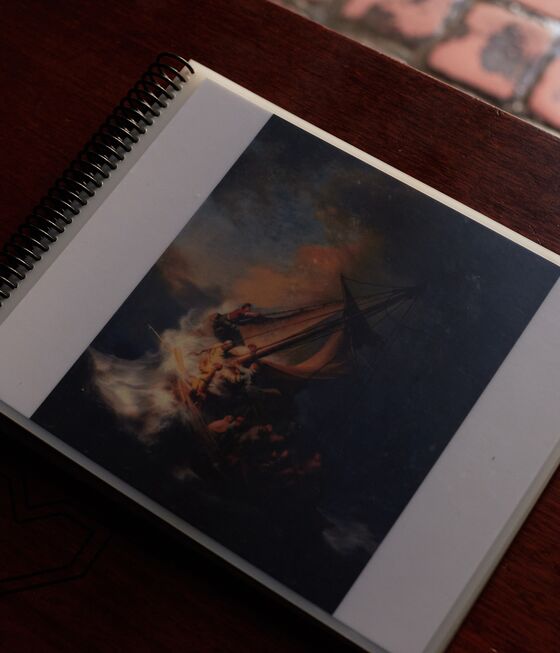

The motion detectors followed the thieves as they made their way upstairs to the Dutch Room, a second-floor gallery that contained some of the museum’s most valuable art. They took three of the four Rembrandts that hung on the wall, including his only seascape; a landscape by Govaert Flinck; and one of the only 36 Vermeer paintings known to still exist. If they’d felt pressed for time they would have just removed the frames from the wall and run off. Instead they took the paintings down, separated them from their frames, and even cut two of the Rembrandt canvases from their stretchers. One of the thieves also spent what must have been several minutes prying a Shang dynasty gu (or vase) from its heavy metal anchor while the other one moved on to the next room and swiped five sketches and watercolors by Edgar Degas. At one point they tried to grab a silk flag that had once belonged to Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, but it was screwed into the wall, so instead they took the 10-inch bronze eagle finial at the end of the flagpole.

According to the motion detectors, the thieves spent 34 minutes in the galleries. Then they hung around the museum for a while. They checked on the security guards—yep, still duct-taped. They went into the security director’s office and took the videotape from the museum’s security cameras, which had been positioned to record the front door, parking lot, and security desk. Finally, at 2:45 a.m., they left. Neither they nor the stolen artwork have been seen again.

Abath and Hestand sat in the basement for another four hours until the morning guards showed up for their shifts. The police—the real police—were called and, because hundreds of millions of dollars in artwork had been stolen, the FBI. Statements were given, damage was assessed, missing works were tallied: 12 pieces from the upstairs galleries and then, what’s this? A small Manet painting had been swiped from a downstairs gallery that, according to the motion sensors, the thieves had never entered. The last person to visit that room was Abath, when he was making his rounds.

“The Manet has always confused me,” Anthony Amore, the chief investigator at the Gardner Museum, told me last fall. Amore is calm and thoughtful, the kind of person who considers his words carefully. He joined the Gardner Museum in 2005, overseeing its security efforts and working as an in-house detective who, the museum hoped, would eventually solve the crime.

The Manet in question was a small impressionist oil painting, only 10 inches by 13 inches, of a dark-suited man enjoying a drink while writing in a notebook at the famous Parisian cafe Chez Tortoni. It, too, had been cut from its frame, which was left on a chair in the security director’s office.

“It’s such a small painting. Why would you bother to remove it from its frame and leave it on that chair?” Amore wonders. Sure, Abath could have stolen it. He’s never been officially crossed off the list of suspects. But he clearly didn’t steal the other paintings, and besides, he’s now a teacher’s aide living a modest life in Vermont—not the profile of someone who’s spent decades harboring millions of dollars in stolen art.

There were other incongruities, too. Most art thefts last less than three minutes, a quick grab-and-dash before police have a chance to arrive. The Gardner heist lasted for almost an hour and a half; how did the thieves know they had so much time? If they targeted the Rembrandts and the Vermeer because they were worth a lot of money, why did they leave the museum’s most valuable painting, Titian’s Rape of Europa, which art historians have called one of the most important examples of Renaissance art? Amore has been contemplating these questions for 15 years and still doesn’t have any answers. The Manet, though, particularly irks him. “It’s really emblematic of the whole investigation,” he says. “The deeper and deeper you dig, the more questions are raised.”

What happened at the Gardner has become the most famous art heist ever, not only because of the money involved—the value of the missing works, now estimated at $500 million, makes it the largest art theft in history, and the museum’s $10 million reward makes it the most lucrative for anyone who solves it—but also because of the countless FBI agents, private detectives, art dealers, and armchair sleuths who’ve tried and failed to solve it. The statute of limitations ran out on the actual robbery years ago, and the museum has publicly promised not to prosecute anyone who admits to having the paintings, as long as they’re returned. And yet the silence endures. The theft has been the subject of books, documentaries, and podcasts. Copies of the paintings occasionally show up on television shows, subtle references to a character’s criminal past. On The Simpsons, Mr. Burns was once arrested for possessing the stolen works. A copy of one painting used on the show Monk looked so real, the FBI called the producers to double-check that it was a prop.

The Gardner heist has attracted a cottage industry of private detectives of varying levels of legitimacy, all claiming to be hot on the paintings’ trail. “I’d say I’m working on it on a weekly basis,” says Arthur Brand, an art historian-cum-detective who lives in Amsterdam. Brand offers himself as a go-between, someone criminals can come to when they want to anonymously surrender stolen art—last year he facilitated the return of a $28 million Picasso that had been snatched off a yacht on the French Riviera 20 years earlier. In 2017, Brand told Bloomberg he’d have the Gardner’s paintings returned to the museum within months. It’s been three years.

“A lot of guys in this industry just say things to get press,” says Robert Wittman, a retired FBI special agent who founded the bureau’s Art Crime Team. “Every few years someone will call up a newspaper and say, ‘We’re going to get the Gardner paintings soon.’ ” The most famous example of this happened in 1997, when a Boston Herald reporter claimed an antiques dealer showed him one of the Rembrandts—“We’ve Seen It!” the Herald boasted on its front page. Then an analysis of some paint chips indicated it was probably a fake. Another analysis contradicted that conclusion, but the art dealer didn’t offer further proof, and the painting was never returned.

“The Gardner is the big one. It occupies most of my time,” Charley Hill, a retired art and antiquities investigator for Scotland Yard, told me last year when I called him up to discuss an entirely different art theft. Of all the private detectives nosing around the case, Hill has the most impressive résumé. During his time at Scotland Yard he recovered an estimated $100 million in stolen art. In 1993, for example, he retrieved Vermeer’s Lady Writing a Letter With Her Maid, which had been lifted seven years previously from the Russborough House, a private estate in Ireland. The following year, Edvard Munch’s The Scream was stolen from the National Gallery in Oslo; to get it back, Hill posed as a representative of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles who was willing to buy the work.

Hill is 73 now. It’s been a long time since he last worked for Scotland Yard. These days he mostly putzes around his garden “getting bored and fat,” but he still investigates the occasional theft. For the past few years he’s been working on the Gardner case. “A person, a key player, rang me this morning,” he told me. “I hope to see him straightaway.”

The Gardner Museum—and the 16,000 paintings, sculptures, and ceramics that make up its collection—are the doing of one woman. Isabella Stewart Gardner inherited her wealth from her father, a linen merchant who died in 1891. She and her husband, Jack Gardner, a Boston merchant whose family had also amassed a sizable fortune, used her inheritance to buy art. They traveled frequently to Europe, returning with sculptures, ancient Roman vases, and sometimes a Rembrandt or two.

After Jack died in 1898, Isabella moved out of their Brookline mansion and into an even grander one she’d built in Boston’s Fenway district. It was a re-creation of a Venetian palace, complete with columns, stone arches, and an open courtyard filled with lush greenery. Gardner covered its walls with works by Titian, Vermeer, Botticelli, Degas, and a portrait of herself that she commissioned from John Singer Sargent. In glass cases she put illuminated manuscripts, 11th century Chinese statues, and an early copy of Dante’s The Divine Comedy.

Gardner died in 1924, and in the absence of heirs (her only child had died young), she left everything to the public. There was one catch: According to her will, the works couldn’t be rearranged, sold, or donated, and new art couldn’t be added. If these conditions were ever violated, the entire collection, along with the house and the land, would be turned over to Harvard. The walls of what soon became known as the Gardner Museum have remained unchanged ever since.

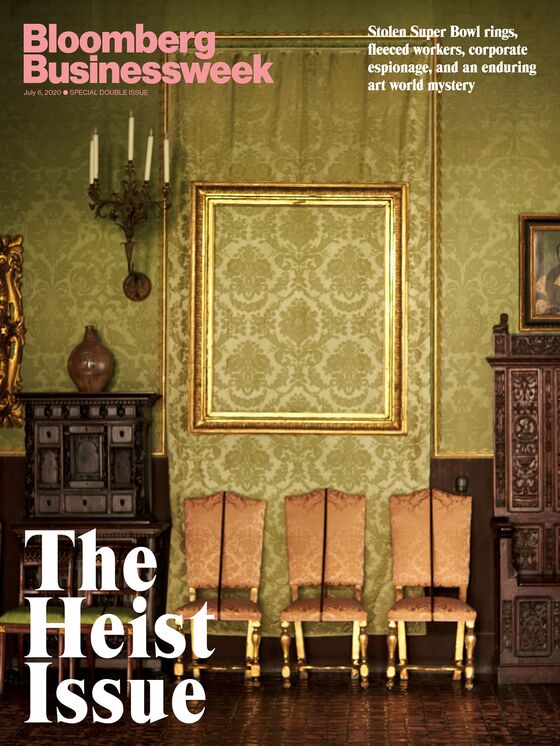

This posed a problem after the theft. There were glaring blank spots on the walls where the stolen paintings had hung. According to Gardner’s will, the museum wasn’t allowed to fill them. So it just rehung the empty frames, a visual testament to what had been lost.

Over the years the pictureless frames have become one of the most famous features of the museum. Visitors stand thoughtfully in front of them as if willing the paintings to reappear. In a way, they’ve become their own exhibit—a reminder that while we value great beauty, we also destroy it.

It’s a little bittersweet for Amore that people flock to the museum to see the artwork that isn’t there, instead of everything that still is. “I understand it, it’s an unbelievable mystery,” he says. But sometimes he worries that the sensationalism of the heist has overshadowed what was taken. The missing paintings are physical relics from hundreds of years ago, the truest capture we have of an unphotographable past. For the price of a museum ticket, anyone could study the actual brushstrokes Rembrandt put to canvas. Now they can’t. “The money isn’t what keeps me going,” Amore told me last year, as we toured the museum. “It’s the tragedy that something irreplaceable has been lost.”

Amore’s approach to the investigation is to tackle it with fastidiousness: If he replies to every email and follows up on every tip, no matter how far-fetched, eventually something will pan out. He works closely with Geoff Kelly, the FBI agent who leads the bureau’s investigation on the case.

Kelly is the latest in a long string of FBI agents assigned to the investigation. Over the decades the bureau has carried out undercover operations everywhere from Miami to Japan, each with a different set of potential thieves, each ending in disappointment. Wittman, the retired FBI agent, is convinced that the 2006 sting he worked in France—he posed as a shady collector willing to buy the paintings from Corsican gang members—was the real deal. “I think they did have access to the paintings,” he says. “Are they still in France? I don’t know, it’s been years.” (“We don’t believe they’re in France,” Amore says flatly.)

These days the FBI’s current theory, and the one to which Amore gives the most weight, is that the paintings were stolen by low-level associates of one of Boston’s organized crime rings. For a while the bureau thought they might be held by a mobster named Carmello Merlino, who in 1998 was caught on an FBI wiretap claiming he knew where they were. But when Merlino was arrested for attempting to rob an armored car depot and given the opportunity to turn over the paintings in return for a more lenient sentence, he couldn’t produce them. He was sentenced to 47 years in prison, where he died in 2005.

“Mel begged me to tell him where the paintings were. He thought I could find out who had them so he could help return them,” says Martin Leppo, Merlino’s former defense attorney. Leppo, who’s 88, worked as a criminal attorney in Boston for more than 50 years and represented seven clients who at various times have been considered persons of interest in the case. As far as he knows, none of them did it.

In 2013 the FBI made the unprecedented move of announcing that it knew the identities of the two original thieves, both of whom are believed to be dead. Amore agrees with their conclusion. “We haven’t released the names of the people we believe were involved, but I’ll say we’ve gotten a good amount of credible information on them,” he says. He and the FBI have also tracked the art up to a 2003 exchange between two mobsters in a Maine parking lot, but they’re not sure what happened after that. The assumption is that the paintings are still somewhere in New England. “This whole thing has been utter insanity,” Leppo says. “Nobody knows who did it or where the stuff is.”

“Oh, they’re in Ireland,” Hill says. He tells me this casually, confidently, as if there couldn’t possibly be another explanation. “Anthony Amore knows my thoughts,” Hill says. “He always says, ‘Charley, you’re wrong.’ ”

Amore is more measured in his response. “I have great respect for Charley, but he thinks everything stolen ends up in Ireland.”

For years, Hill insisted the Boston mobster Whitey Bulger had given the Gardner works to the Irish Republican Army, which is rumored to have trafficked in stolen art. When Bulger was arrested and the paintings still weren’t found, Hill revised his theory. Now he says that if Bulger was involved, it was only peripherally. He says he believes the two original thieves, loosely affiliated with the IRA but not acting on its behalf, traveled from Ireland to steal the art.

“Two clues jump out at me,” Hill says. “One, the crime happened the night of St. Patrick’s Day,” which, he points out, is an important Irish holiday. “Two, one of the robbers used the word ‘mate’ when he tied up the security guards. That’s not a word Americans say.”

“That’s a new one from Charley,” Amore says. “I hadn’t heard that one before.”

“One of the thieves did use the word ‘mate,’ ” Hestand, one of the security guards, wrote to me in an email. But Hestand insists they had American or Canadian accents. “I never had any reason to think they were from outside North America.” It’s true that Irish organized crime rings sometimes stole artwork, but they usually targeted places much closer to home. The Russborough House, for example, has been robbed four times: by an IRA-affiliated gang in 1974, then by an Irish criminal named Martin Cahill in 1986; then in 2001 by Cahill’s protégé, Martin Foley; and finally in 2002, by a group (possibly involving Foley again) who stole some of the same paintings Cahill took in 1986. Both Amore and Wittman are wary of Hill’s theory. As Amore points out, “Why would the IRA travel to Boston to steal a Rembrandt when there are plenty of them in Europe?”

“I have no hard evidence whatsoever,” Hill admits. But he’s undeterred. The “key player” he visited last year turned out to be Foley. According to Hill, Foley wasn’t involved in the original theft but knows where in the rolling Irish countryside the paintings are hidden. For more than a year, Hill has been traveling back and forth to Dublin to meet with Foley and devise a plan for the return of the artwork.

“Martin is worried,” Hill told me last summer, when I visited him in London to see how his plan was progressing. “He’s concerned that if he comes forward with the paintings, he’ll be prosecuted.” At the time, Foley was being sued by Ireland’s Criminal Assets Bureau for the equivalent of almost $830,000 in back taxes—ironic, considering he owns Viper Debt Recovery & Repossession Services, a company people hire to recoup money they’re owed. I pointed out that if he really did have the paintings, the museum’s $10 million reward would be more than enough to pay off his debt. Hill said Foley was more worried about the FBI and Ireland’s laws against profiting from organized crime.

“That’s ridiculous,” Amore says. “I’ve written Charley many messages explaining how this can be resolved, and he never responds to that part of the message.”

When I asked if I could speak to Foley, Hill said no. “The people involved in recovering this are not people you’d want to introduce to your mother,” he explained. “I don’t want anybody murdered.” Every few months I’d check in with Hill, but nothing changed. Foley was ready to lead authorities to the artwork, he’d tell me, but he needed an official assurance of immunity. At one point last year, Hill wrote to a Massachusetts congressman asking the U.S. government to step in—but he did so around the time that Robert Mueller’s report on Russian interference in the U.S. presidential election was publicly released. A 30-year-old art heist was not Congress’s top priority. He received no response.

In February, Ireland’s Supreme Court ruled that Foley owed the back taxes. According to Hill, Foley then went into hiding. My emails to Viper Debt Recovery went unanswered. “I haven’t spoken to Martin since February,” Hill says. He’s not sure where he is. Instead he’s found a new source—he won’t say who—to take him to the place, “in or around Dublin,” where the new source says the paintings are hidden. Hill plans to meet with him in August.

There’s no Agatha Christie detective to show up at the end of this story, lock all the suspects in a room, and calmly unravel the clues one by one for a comforting and satisfying conclusion. In fact, one of the most intriguing aspects of the Gardner heist is that even the people who are trying to solve it can’t agree on what happened. Did Abath steal the Manet? “He’s just a regular guy,” says Brand, the Amsterdam art historian. Amore isn’t so sure. “When you’ve eliminated all the other possible theories, the most obvious one remains,” he says. Are the 13 stolen pieces even still together? “Yes,” Hill says. “I don’t believe so,” Brand says. “Some of the paintings may be together,” Amore hedges. Wittman, the retired FBI agent, points out that “there’s a possibility they could all be destroyed.”

The Gardner is closed to the public right now because of the pandemic, but Amore still goes into work every day, walking the halls of the empty museum and tracking down potential informants. “It’s been so long that a lot of people are dead,” he says. “Others have moved. Wives have become ex-wives. It takes a lot of skip tracing.” When he gets to an impasse, he turns back to the tens of thousands of pages of FBI files that litter his office. “What if it’s right under my nose, and I’ve been looking at all the wrong clues?” he wonders. “Somewhere in there has to be the answer.”

Leppo, the defense attorney, isn’t searching for the paintings, but even he can’t seem to leave the case behind. “So many people bother me about this that my secretary sometimes tells me, ‘You have another painting call,’ ” he says. They assume that, given his client roster, he either knows where the missing works are or knows someone who knows someone who does. A couple of years ago, for instance, a woman walked into his office and told him her father had been involved in the theft. She implied that she knew where some of the artwork was hidden, but when Leppo asked if he could see it, she demurred. He hasn’t heard from her since.

Leppo doesn’t know if the woman was telling the truth. So many people have put forth so many theories that at this point it’s hard to say what’s real. “Somebody called me the other day—I’m not going to mention who—and said, ‘Do you want to take a trip to Saudi Arabia? I’ve got an in on the paintings,’ ” he says. “I said, ‘Call me when you find them.’ ”

Read next: How Thieves Hacked $3 Million From a London Art Gallery Sale

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.