Investors Buy Rights to Hits by Acts From Bon Jovi to Al Green

Investors Buy Rights to Hits by Acts From Bon Jovi to Al Green

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Bon Jovi’s Livin’ on a Prayer was the Billboard No. 1 hit for four weeks, the official video has more than 690 million views on YouTube, and it’s an enduring anthem of Gen X’s hairspray-drenched mid-1980s glory days.

Jon Bon Jovi, the band’s lead singer, did not care for the song initially and had to be convinced of its merits by guitarist Richie Sambora. Thankfully, the band’s most celebrated hit was saved. “I always look at songs as houses,” Sambora says on the phone from Laguna Beach, Calif. “And Livin’ on a Prayer was a mansion.”

The real estate comparison is apt. Earlier this year, Sambora, who co-wrote the song, sold this and many of his other prized assets to Hipgnosis Songs Fund Ltd., an investment vehicle publicly traded in London. The fund works a little bit like a real estate investment trust, which holds a portfolio of property. Similarly, Hipgnosis, launched in 2018, allows billion-dollar pension funds and mom and pop investors access to royalty streams and intellectual property from a selection of tunes made famous by artists as diverse as Adele, the Eurythmics, and Al Green. The fund just raised £236 million ($297 million) in a share sale to help pay for further acquisitions.

Hipgnosis, named for a now-defunct design group that made iconic album covers, is run by Merck Mercuriadis, who used to manage artists such Elton John, Beyoncé, and Iron Maiden. The stock is up more than 10% this year, making it a rare bright spot on the London Stock Exchange, where many companies have been roiled by the spread of coronavirus and subsequent lockdowns.

In fact, lockdowns have brought about new opportunities for those in the business of buying songs, with artists looking for alternative ways to get cash as the money they might have made from live shows vanishes. “There’s no question that our pipeline, which was already pretty massive, has grown during the course of the pandemic,” says Mercuriadis. “A lot of artists are going to not be able to tour for the next couple of years.”

With Hipgnosis, Mercuriadis is attempting to leverage his experience in the music business to match two seemingly disparate worlds: that of songwriters and artists eager to earn cash from their music and that of investors—big or small—hungry for yield as bond returns dwindle and virus-hit companies cancel dividends. It’s a market that is attracting a growing number of players. Providence Equity Partners and Warner Music launched the $650 million Tempo Music Investments fund at the end of last year. Primary Wave Music Publishing LLC has raised $1 billion for two intellectual property funds in the past four years and is preparing soon to launch a third, significantly larger fund, according to a person familiar with the matter.

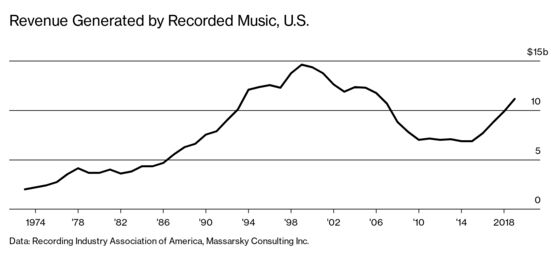

The flurry of activity over the past five years reflects a change in fortunes for music rights as an asset class. From the turn of the century through 2015, revenue from music royalties seemed to be in an irreversible slide. The total money generated by music royalties in 2015 in the U.S. was less than half what was earned in 1999, according to the Recording Industry Association of America.

The first blow to sales came from Napster, BitTorrent, and other file-sharing platforms. By the time the industry cracked down on file sharing, consumers had lost the habit of buying expensive CDs. “That had a big effect on investors,” says David Pullman, who’s best known for turning David Bowie’s music royalty flows into “Bowie bonds” in 1997. “At that same time, the entire securitization market shut down,” Pullman says, referring to the financial crisis of 2008.

The slump has been reversed in recent years as the industry learned to make money from streaming. Platforms such as Spotify and Apple Music offer consumers an inexpensive way to listen to their favorite songs—either through subscriptions or by sitting through some ads—coupled with an unprecedented level of choice. In 2019, music streaming accounted for more than half the revenue recorded by the RIAA, compared to less that 12% five years earlier. “It has picked up the record industry and literally saved it,” says Nari Matsuura, head of New York-based Massarsky Consulting Inc.’s valuation practice. While the business has not returned to levels seen around the turn of the century, “we are on a trajectory to get back to that place relatively soon.”

The pandemic, while hitting performer’s live revenues, has not significantly dented streaming numbers. There was an initial slowdown when commuting habits were interrupted, but streaming has recovered in the months since, according to funds and industry watchers. Spotify, the world’s largest streaming audio service, added 15 million monthly active users in the first three months of the year, according to its latest trading update. Hipgnosis saw its streaming revenues rise in the first quarter, making up for losses on the revenue it earns when songs are performed live. “In a recession, we don’t stop listening to music,” says Paul Flood, a fund manager at Newton Investment Management Ltd., who counts Hipgnosis as one of his top investments. “You might listen to a little bit of Leonard Cohen or something a bit more depressing when you lose your job, but you still listen to music.”

Though streaming revenue may be an attractive opportunity for investors, it’s been no panacea for artists, who often struggle to make ends meet. The majority of streaming platforms pay only fractions of a cent for a single play. The fact that money managers are swooping in to buy has its pros and cons, says Crispin Hunt, chair of Ivors Academy, which represents the interests of songwriters and composers in the U.K. While funds could be a powerful force in showing that songs have real value, the organization does not agree in principle with music writers selling their art.

“Hopefully, the investors getting involved in the value of the song and the long-term return that they can hope to get will help drive value back into the song,” says Hunt. But once it becomes clear that music is valuable again, he adds, “I think people will be very reluctant to sell their rights, because they know it’s either 100 grand as a pension or 10 grand in the pocket.”

There is a complicated, often unhappy relationship between those who create their music and those who own it. Artists from the Beatles to Taylor Swift to Prince have all fought to own more of their rights or have protested their ownership by others. Bowie, when he issued his bonds with the help of Pullman in the ‘90s, used much of the money he made to buy back his own work from a former manager.

Along with the financial incentive, artists are often keen that their music not be used in a way they object to, but selling the rights also means that the new owner can decide where that music is used. “I don’t ever want there to be negative emotion about having made the sale,” Mercuriadis says. Even after the rights are sold he makes sure “that the artist knows what’s happening so that they’re not blindsided on a Friday night if they hear an interpolation of their song, or a new cover version, or whatever the case may be.”

Even for some of the most successful writers, there’s an appeal to realizing a return now on assets that will have to be managed for decades to come. “What are you gonna do, give them to your kids? And they don’t know what do with it,” says Sambora. “I probably won’t exist that many years but the songs will continue.” —With Vernon Silver and Laura Wright

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.