FedEx Ground Delivery Becomes a Road to Riches for Contractors

FedEx Ground Delivery Becomes a Road to Riches for Contractors

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The crowd was amped. Some 1,800 strong, they had traveled from across the country amid a raging coronavirus flare-up to assemble in a hotel ballroom in Nashville. The man they were cheering as he took the stage wasn’t a rock star, a preacher, or a politician. It was Spencer Patton, a bespectacled 35-year-old former hedge fund manager in a polo shirt and khakis. Patton has carved out a niche doling out advice to entrepreneurs looking to make it big as contractors for FedEx Ground, the package-delivery service that’s been booming amid a surge in online shopping during the pandemic.

“This is like buying Apple at $1 a share—that’s what we’re doing here,” Patton told rapt attendees packed into the presidential chamber at the Gaylord Hotel. “We’re at the tip of the spear in an asset class that no one knows about.”

The unusual asset class Patton proselytizes about—contracts that give owners the right to operate FedEx Ground routes in specified areas for as long as three years—is red-hot these days. The owners collect a fee for each package their fleets drop off, but they’re entirely responsible for hiring drivers, buying trucks, and dealing with all the issues that come with running a small business. Prices for routes have increased 50% from only a few years ago, but they still may bring returns of more than 20% a year. Patton predicts most contractors will see their sales double over the next three years. Meanwhile, the mom and pops that dominated the industry are selling out to a new class of investors looking for growth and higher returns.

Patton’s celebrity status stems from his deep knowledge of the business: He owns 250 routes across the country, and he estimates that his consulting company, Route Consultant, has brokered about 25% of all the FedEx Ground route transactions in the U.S. So the nation’s thousands of would-be delivery czars are eager to get Patton’s advice on everything, including how much to pay for routes, the latest safety standards, and the skills needed to operate in the urban gridlock of Chicago or the rural byways of Chugwater, Wyo.

Patton came to logistics stardom via a circuitous path. Growing up in Nashville, he got his first taste of trading stocks at age 10 at his dad’s urging and was dabbling in options by age 16. After graduating from Vanderbilt University in 2008, he joined a company in Nashville that bought struggling businesses and turned them around. Two years later he persuaded the partners there to kick in $2 million to back a hedge fund he’d started.

In 2013, Patton walked away from managing other people’s money to concentrate on his own business. He’d methodically studied different industries, including self-storage units and liquor stores, before settling on the then-obscure idea of buying FedEx Ground delivery routes.

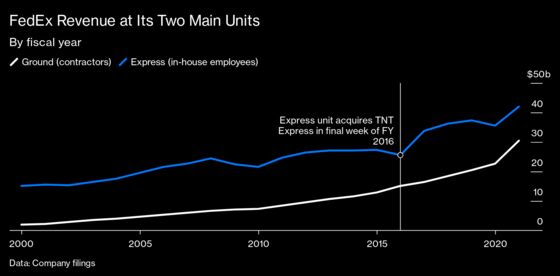

Patton’s opportunity stemmed from a decision two decades earlier by FedEx Corp. founder Fred Smith to buy a small parcel company, which quickly became a growth engine and is now the crown jewel of his delivery empire. Annual revenue has tripled over the past decade, to $30.5 billion, while sales at the company’s Express unit, which transports mostly by air and has its own fleet of drivers on the payroll, have increased about 60% during the same period, to $42 billion. Average profit margins at Ground over the last two decades have been more than twice those at the Express business.

Unlike the overnight service, which hires its drivers directly, Ground operates on short-term contracts with 5,600 small companies. That’s given it a lower cost structure than rival United Parcel Service Inc., which has a unionized workforce and pays the industry’s highest wages. A UPS driver with over four years on the job makes about $65,000 a year, not counting overtime, plus pension and health benefits. Delivery driver pay at FedEx Ground depends on the independent contractor and the location; it can range from about $39,000 a year to $60,000 for a high-performing employee. This doesn’t count benefits, which most contractors don’t offer.

Eight years ago, when e-commerce was shifting into high gear, Patton began to build his own route operations, which now deliver FedEx packages in 10 states. Along the way he began building a consulting business for newbies or others looking for advice. Eventually he added deal brokering, truck leasing, driver training, and even a financing unit to round out his suite of services—comprising 26 entities in all.

Since 2019, FedEx Ground has overhauled operations to account for the boom in at-home shopping. Smith extended deliveries to seven days a week from five, updated routing software, and started accepting more large packages, and FedEx Ground began taking back small packages that previously were passed to the Postal Service for final delivery. Then the pandemic hit, and volume jumped 23%, to 3.1 billion packages last year.

The operational changes and accelerated growth at FedEx Ground have overwhelmed many contractors and spurred an unprecedented frenzy of route buying and selling, Patton says. Longtime FedEx contractors, many of whom started out driving their own truck and have since accumulated wealth along with more delivery routes, are selling as the value of their holdings rises.

“We are seeing a ton of old-school contractors who are … retiring, cashing out, and making great money,” Patton says. “The new people coming in are business savvy and capitalized, and they’re hungry to grow.”

Patton lures potential clients with a weekly webinar that teaches the basics about FedEx routes. Every week he also announces the location of FedEx routes up for grabs and offers his services to support sales or purchases. Patton now has 70 employees at Route Consultant after starting three years ago with only four.

Typically, entrepreneurs can buy 10 FedEx routes for about $1.25 million. Annual operating profit for the small-package-delivery businesses can range from 10% to as much as 25% of sales for a well-run operation, Patton says. Prices for individual routes are based on a multiple of operating cash flow, while the price paid per package depends on a route’s population density, typical number of stops per mile, and the types of packages usually delivered. Valuations have climbed to about 4.5 times operating cash flow, up from about 3 times only a few years ago as package delivery expands.

FedEx signs off on each new owner, but it doesn’t get involved when routes get bought or sold. The courier must take a hands-off approach to the contractors, known as independent service providers, to avoid lawsuits from drivers who otherwise might claim they really work for FedEx. Amazon.com Inc. is also using the contractor model, which wards off union organizers and keeps costs down, as the company builds its own delivery network.

Patton’s expo attracted those 1,800 people this year, with sponsors including vehicle outfits Ryder System Inc. and Isuzu Motors Ltd. That’s up from about 400 at the first expo in 2019 and about 750 in 2020. At such gatherings, Patton always begins his talks with disclaimers that he’s not a FedEx employee and doesn’t speak on behalf of the company and that FedEx doesn’t endorse his consulting business. At this year’s event, after light banter and a soft sales pitch for Route Consultant, Patton revealed previously unannounced changes to safety training that FedEx Ground plans to roll out. Attendees furiously scribbled notes.

One of those in attendance in Nashville was Larry Murray. A marketing professional who before the pandemic helped organize tours and festivals including Willie Nelson’s Luck Reunion in Texas, he says he binge-watched Patton’s webinars for four days and then signed onto the consulting program in 2020 before buying nine FedEx routes this year in Belton, Texas. Patton’s team helped value the business and get Murray started.

“Every penny was worth it,” Murray says. “We would be in really bad shape if we hadn’t done that.” He aims to buy more routes within the next year. Patton has “laid out a great road map,” he says.

Sean Randall, a career banker who last worked at Citigroup Inc.’s wealth management unit, quit corporate America in 2020 to be his own boss. He’d invested in apartment buildings but said they’ve gotten too expensive to produce a decent return. After watching the webinars and podcasts, Randall hired Patton’s company as a consultant and bought FedEx routes in the Washington metro area in January 2020. “There’s a lot of opportunity,” Randall says. “Because of that growth, a lot of smaller operators are being forced out. It’s too much for them to handle.”

FedEx has contributed to the hot market for buying and selling routes by limiting contractors from handling too much of the volume at one FedEx hub. It typically tries to keep a single contractor at less than 10% of a hub’s total volume, lowering the risk in case an independent operator stumbles and FedEx has to find other contractors to pitch in to get the packages delivered.

Todd Smart, in Mansfield, Ohio, got his first delivery area from FedEx Ground in January 1999 on the condition that he would buy and drive a new vehicle. From that beginning, Smart now has amassed 70 routes and started a repair shop for his vehicles and others. He needs to pare back to comply with FedEx’s hub limits. “The expectation is that if I sell half of my business, I will still grow by double in three years,” Smart says.

The system works most of the time, but it does have its quirks. When an operator fails, FedEx calls on other contractors to pitch in and pays them an extra stipend per package to help get the emergency under control.

Some contractors keep contingency teams on hand to send to areas where help is needed. Jim McCarthy, who formed a business with his sons that’s amassed 120 routes in multiple states, has four teams with five members each that travel all over the U.S. to do contingency work, renting out a large house wherever they’re needed. The groups earn more per package, and if the routes ever become available, McCarthy’s business is likely to be in a good position to vie for them. “Spencer opened my eyes to a bigger picture,” he says. “He brings a big business perspective to a little business.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.