The Most Dovish Fed in History Is on a Mission to Spur Inflation

The Most Dovish Fed in History Is on a Mission to Spur Inflation

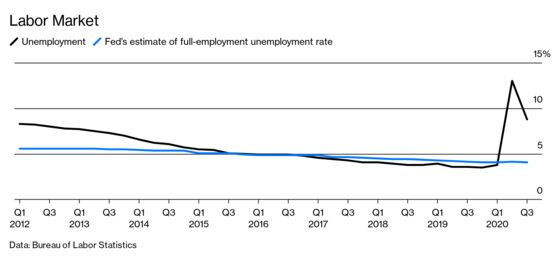

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has done everything to demonstrate his desire for higher inflation short of dressing up as a dove and cooing in front of Fed headquarters. In August he unveiled a policy that not just tolerates but seeks periods of inflation above the Fed’s 2% target. “The labor market is recovering, but it’s a long way—a long way—from maximum employment,” Powell said at a Federal Open Market Committee press conference in September. Asked whether the Fed wants to get unemployment back down to 3.5% or below—a degree of labor market tightness that previous Fed chairs feared would set off spiraling inflation—he said, “Yes, absolutely.”

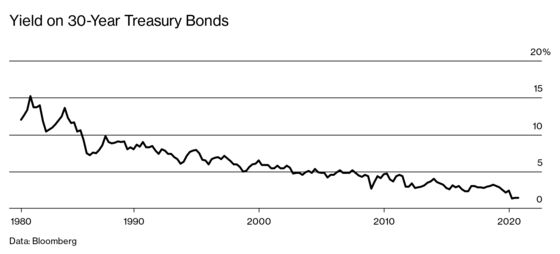

Powell’s pro-inflation message isn’t having the intended effect, though. The Fed’s low rates have pumped up the stock market. But if the financial markets were taking him at his word, long-term interest rates would be leaping to compensate investors for higher inflation’s impact on the purchasing power of their bonds’ coupon payments. Not yet: The yield on the 30-year Treasury bond is still just 1.6%, up from 1.4% the day before Powell’s Aug. 27 speech at this year’s virtual version of the annual central banking conference held in Jackson Hole, Wyo. A yield that low implies that either investors don’t think Powell can achieve 2% inflation, or they’re resigned to 30 years of negative inflation-adjusted returns. Either possibility is depressing.

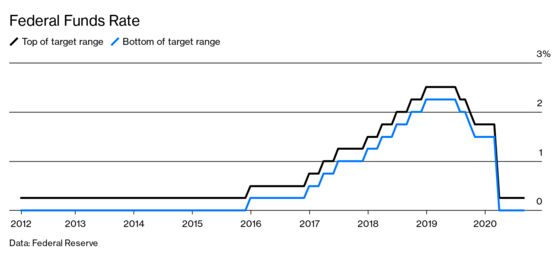

Inflation that’s chronically too low remains a perplexing challenge for central banks, which have an easier time fighting inflation that’s too high. If Powell can’t convince consumers, companies, and investors that the Fed can raise inflation, bad things could happen. A Japan-like deflationary psychology could set in as households and businesses put off buying big-ticket items—whether cars or machine tools—in the expectation that prices will fall. What’s more, low inflation and soft demand for loans have combined to push interest rates to the floor, which robs the Fed of its No. 1 tool for fighting recessions. It can’t cut interest rates significantly because they’re already about as low as they can go.

To avoid the vortex of outright deflation falling prices—the European Central Bank cut its key short-term interest rate below zero in 2014. The Bank of Japan followed in 2016. Powell’s Fed has resisted going subzero, but it’s ahead of its peers in one respect: It’s the first to embrace overshooting its inflation target to compensate for periods of undershooting.

Economist Paul Krugman wrote in 1998 that to stir growth when interest rates are near zero, the central bank must “credibly promise to be irresponsible—to make a persuasive case that it will permit inflation to occur, thereby producing the negative real interest rates the economy needs.” “Irresponsible” is not a word one would apply to Powell and his sober peers on the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee. He’s aware of the perception problem: “This is all about credibility. We understand perfectly that we have to earn credibility,” he told reporters after the meeting of the FOMC on Sept. 16.

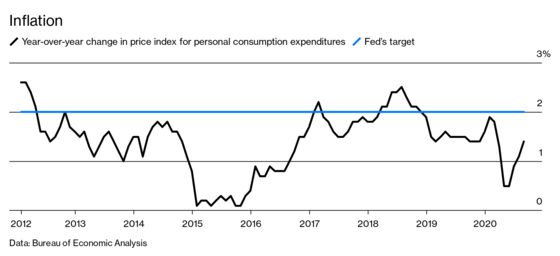

A reputation for probity at the Fed that’s so good it’s bad isn’t the only thing keeping inflation undesirably low. The pandemic, by suppressing demand for goods and services, has knocked down the measure of inflation that the Fed watches—the year-over-year change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures—to just 1.4% in August. Meanwhile, the economic recovery is faltering because coronavirus relief programs have expired. In a speech on Oct. 6, Powell warned of “tragic consequences” for racial and wealth disparities if relief isn’t extended. But hours later, President Trump cut off negotiations with congressional Democrats until after the election.

Even before Covid-19 struck, U.S. economic growth depended on ultralow interest rates, big federal budget deficits, and an unsustainable rate of business borrowing. (And while growth helped the poor by creating jobs, it helped the rich even more by swelling their portfolios.) In September the Congressional Budget Office projected that the U.S. economy would grow only 1.6% annually for the next 30 years, well below the 2.5% rate of the past 30. Harvard economist Lawrence Summers, who was President Clinton’s Treasury secretary and headed President Obama’s National Economic Council, argues that cutting interest rates alone can’t cure what he calls secular stagnation, so Congress needs to do more deficit spending, encourage investment, and discourage saving. “I sort of suspect that we’re past peak central banking,” he said in May in a Princeton webinar.

The Fed’s new inflation policy is in part an admission that the old rules no longer apply. Policymakers used to assert with confidence that an unemployment rate below 6% would lead to high inflation. Yet even when unemployment hit a low of 3.5% in February, inflation remained below the 2% target. Neel Kashkari, the dovish president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, has disparaged theories tying low unemployment to inflation as “ghost stories.”

The policy unveiled by Powell at the end of August removes the long-standing promise to react to very low unemployment. From now on the Fed will react only to high unemployment. And instead of focusing on a single number—the national unemployment rate—it’s promising to consider low- and moderate-income Americans, some of whom need unemployment to be very low before employers will consider hiring them.

These are unusually dovish policies for the world’s most powerful central bank. If inflation has been running “persistently” below 2%, the Fed “will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time,” the new policy says. The FOMC got more specific at its Sept. 15-16 meeting, saying it won’t raise rates until inflation has reached 2% and is “on track” to moderately exceed it for some time. With these changes, U.S. monetary policy “is as easy as it’s ever been in modern times, or even in nonmodern times,” says Padhraic Garvey, head of research for the Americas at ING Bank NV.

But will it work? David Wilcox, a former Fed official who’s a senior nonresident fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, calls it “a very substantial step forward.” Allison Boxer and Joachim Fels, both of Pimco, a big bond investor, are skeptical. “We wonder if the Fed leadership is using surprises and emphatic language to try to compensate” for an FOMC “that may not be fully on board with a more significant regime shift,” they wrote in a note to clients.

Investors would have been more impressed if the Fed had supplemented its promises with actions, such as an increase in purchases of medium- and long-term Treasury securities to stimulate economic growth, says Aneta Markowska, chief financial economist at Jefferies & Co. “They didn’t seem to see the urgency. They think what they’re buying now is a lot. And it is a lot. But they could have done a little bit more,” she says. “I feel it was a wasted opportunity.”

For the Fed, promises are easy to make but could be hard to keep. When it comes time to let inflation run above 2%, there are likely to be shrieks of pain from the bond market and people living on fixed incomes. Willfully allowing inflation to go above target will seem reckless; why, inflation hawks are sure to ask, should the Fed risk igniting high inflation after it’s already achieved its purpose of eradicating deflationary psychology?

Members of the FOMC may be tempted to raise interest rates quickly after inflation has gone above 2%, rather than let the rate average 2% over any meaningful period. The consensus on deliberate overshooting already shows signs of cracking. Robert Kaplan, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, dissented at the September meeting of the FOMC from the promise to keep rates low at least until inflation hits 2%, preferring “greater policy flexibility.”

It’s hard to credibly promise to do something that will seem wrong to you when the time comes to act—an insight that helped win a Nobel Prize in economics in 2004 for Finn Kydland, now at the University of California at Santa Barbara, and Edward Prescott, now at Arizona State University. (For a political analogy, consider Republican Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, who promised not to fill a Supreme Court vacancy in a presidential election year, then thought better of his pledge when the time came.)

Still, Powell and the rest of the FOMC need to convince the markets and consumers that they really, really mean it this time. A firm rule can help by tying bankers’ hands. When high inflation was the concern, University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman advocated a “k-percent” rule that said that if the Fed committed to increasing the money supply by the same low percentage each year, inflation would be mild and predictable. Fed Chair Paul Volcker, the giant who broke the back of inflation in the early 1980s, professed to follow a money-growth rule, though in practice there were dramatic fluctuations in the money supply.

Alan Greenspan, who succeeded Volcker, was not a rules guy. He cultivated the image of an inscrutable maestro and said in a 1988 speech, “I guess I should warn you, if I turn out to be particularly clear, you’ve probably misunderstood what I said.” Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen, the next two Fed chiefs, were economic scholars from Princeton and the University of California at Berkeley, respectively, who believed rules enhanced credibility. They targeted consumer prices rather than money growth. The Fed, which had informally aimed for 2% annual inflation since the Greenspan era, made itself strictly accountable for achieving 2% by publicly adopting it as a target in January 2012.

To the consternation of Fed officials, the central bank’s favored measure of inflation has come in below 2% in all but 15 of the 103 months since the 2012 pronouncement. Low interest rates are part of the problem. The Fed can’t keep inflation from falling when the economy is weak because there’s no room to cut rates to rev up growth. In contrast, it can keep inflation from getting too high by raising rates to cool growth. Because of that asymmetry, inflation readings below 2% have been far more common than readings above it.

Powell, a former investment banker, Treasury Department official, and private equity investor, telegraphed his dissatisfaction with the status quo in August 2018 at the Jackson Hole conference. It was six months into his term as chair after six years as a board member. He questioned the usefulness of two key inputs into the Fed’s interest-rate-setting formula: “r-star,” the neutral rate of interest that neither accelerates nor retards growth, and “u-star,” the lowest the unemployment rate can go without igniting excessive inflation. Unlike the stars that navigators once steered their ships by, Powell said, r-star and u-star move around, making them unreliable guides. He expressed admiration for how Greenspan trusted his own hunches about the U.S. economy rather than the “shifting stars.”

“I don’t think people understand how different a worldview” Powell brought to the chairmanship, says Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “Bernanke and Yellen wanted to make monetary policy scientific,” says Vince Reinhart, chief economist of Mellon, an investment affiliate of Bank of New York Mellon Corp. “Powell wants to build the Fed’s constituency with the American public and politicians and to do so by backing away from the image of central bankers in white lab coats.”

Powell wanted to make monetary policy less reliant on unobservable characteristics of the economy such as r-star and u-star, and to finally deliver on the promise of durable 2% inflation. Figuring out how was a key motivation for “Fed Listens,” a 2019 tour of the system’s 12 regions in which Fed officials sought out the opinions of economists, business owners, union members, retirees, and others.

The approach policymakers settled on involves more discretion than the Fed has exercised since the Greenspan era. Powell and others are refusing to say how long or how much they will allow inflation to overshoot 2%. Consider this: Inflation would have to average 3% from now until April 2026 for the price level to reach where it would have been if inflation had been 2% since 2012. It’s unlikely the Fed would let that happen because it doesn’t want shoppers to start thinking of 3% inflation as the new normal. On the other hand, just a month or two of, say, 2.1% inflation wouldn’t be much of a makeup.

Vagueness about the strategy likely helped Powell and Vice Chair Richard Clarida, who was in charge of the policy rethink, achieve consensus between the hawks and the doves on the FOMC. It also gives the Fed some flexibility in case of the unexpected—a sharp drop in oil prices that lowers inflation or a widespread crop failure that raises it.

But fuzzying up the objective guarantees that the Fed will be incessantly badgered to be more specific in the years ahead. And the lawyerly Powell doesn’t appear to enjoy sparring with questioners the way Greenspan did. Asked at the FOMC press conference what the Fed means by “moderate,” Powell said, with perhaps a hint of frustration, “It means not large. It means not very high above 2%. It means moderate. I think that’s a fairly well-understood word.” He then added, “You know, we’re resisting the urge to try to create some sort of a rule or a formula here.”

For many, that’s unsatisfying. “I wish it was a little more specific,” says John Taylor, the economist at Stanford and the Hoover Institution whose own rule for setting monetary policy has informed the Fed and other central banks. Kydland, who’s watched the Fed’s convolutions from Santa Barbara, says, “I do hope they know what they’re doing.” He says he’s inclined to give Powell the benefit of the doubt: “He seems to have his head on right.”

The dream scenario for the Fed is that its messaging works, the economy strengthens, workers earn much-needed raises, consumers open their wallets, and companies are able to raise prices and get back to profitability. Easy monetary policy lubricates the rise in prices. “I actually think they have a much better shot with this new framework,” says Jefferies’s Markowska.

There’s also a darker scenario that could produce rising prices. In that one, easy fiscal and monetary policies are politically difficult to scale back despite rising inflation caused by worker shortages, trade barriers that cut off vital imports, and other factors. In March, Charles Goodhart of the London School of Economics and Manoj Pradhan of Talking Heads Economics wrote in a column for the Center for Economic Policy Research’s VoxEU site, “The coronavirus pandemic, and the supply shock that it has induced, will mark the dividing line between the deflationary forces of the last 30 to 40 years, and the resurgent inflation of the next two decades.”

Resurgent? Perhaps. At the moment, though, Powell & Co. are thinking more about lifting inflation than worrying it will get too high. “It will take some time,” Powell said at the Sept. 16 press conference. “It’s a slow process, but there is a process there.” Spoken like a thoroughly modern, prudently irresponsible central banker. —With Rich Miller

Read next: Cleveland Home Prices Tell Story of Unequal Coronavirus Economic Recovery

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.