Even the Fed Struggles to Nail Down the Meaning of ‘Full Employment’

Even the Fed Struggles to Nail Down the Meaning of ‘Full Employment’

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The year 2019 was humbling for the Federal Reserve. The central bank was forced to unwind a series of interest-rate hikes it had implemented the year before, citing strains on the U.S. economy from President Donald Trump’s trade wars and a global slowdown. In the process, the central bank appeared to be sacrificing its autonomy by caving in to Trump’s relentless demands for cheap money. There was still another reason for the Fed’s reversal, one that goes to the heart of the institution’s dual mandate of ensuring full employment and stable prices. It had underestimated how many jobless Americans were still out there—not technically counted as unemployed but willing to work.

By the time the jobless rate dipped below 4% in the spring of 2018—for only the second time in a half-century—central bankers thought they had accomplished their goal of maximum employment. Their next challenge was to ensure the tight labor market didn’t trigger a so-called wage-price spiral. They began charting a course to raise interest rates high enough to discourage hiring. Yet, unexpectedly, inflation didn’t bubble up, even as unemployment continued to drift lower. It’s 3.5% now.

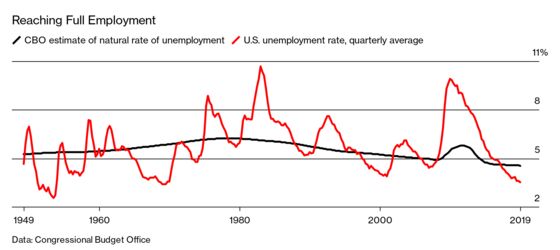

Fed officials are currently engaged in some deep introspection about what they got wrong. At the center of those discussions is the notion of full employment. Zero joblessness is an almost impossible goal, since even in a dynamic, well-functioning labor market there will always be some people who are temporarily unemployed as they move between jobs. What monetary authorities fixate on instead is the sweet spot at which unemployment is low but not low enough to spark inflation. Yet this level can only be extrapolated from past experience. Testifying before Congress in February 2018, just weeks after becoming Fed chair, Jerome Powell acknowledged the inherent lack of precision, saying: “If I had to make an estimate, I’d say it’s somewhere in the low 4s, but what that really means is it could be 5 and it could be 3.5.”

The term “full employment” had intensely political implications from its inception in the depths of the Great Depression. It was more than just a single number estimated under scientific pretenses by central bank technocrats.

In the late 1930s, British economist John Maynard Keynes upended the then-prevailing idea that free markets would automatically provide sufficient jobs for everyone who wanted one. William Beveridge, who’s often described as the father of the U.K.’s modern welfare state, elaborated on Keynes’s ideas in a 1944 book titled Full Employment in a Free Society. Its central proposition was that “the market for labor should always be a seller’s market,” where “people actually feel empowered to say, ‘This job is crummy—I’m going to go and get a comparable job right across the street,’ ” says David Stein, a historian at the University of California at Los Angeles.

In Beveridge’s conception, the responsibility for ensuring this blissful state fell not to the private sector, but to the government. His argument found a receptive audience among voters in the U.S., amid widespread fears that the end of World War II would see a return to Depression-era levels of unemployment. In the 1944 election, Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt and his Republican opponent, New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey, both campaigned on assuring postwar full employment.

FDR won in a landslide, and the following year Democrats in Congress introduced legislation that would solidify that commitment in law. However, Republicans and Southern Democrats balked at institutionalizing a role for government as employer of last resort, according to Stephen K. Bailey, whose 1950 book on the subject remains the definitive account, and pushed for the words “full employment” to be excised from the bill and replaced with “maximum employment,” subject to the “preservation of purchasing power.” And so the Full Employment Bill of 1945 became merely the Employment Act of 1946.

The belief that full employment is inimical to price stability dates to at least the early 20th century. But it was the work of Milton Friedman that transformed an ideology long promoted by business interests into economic theory. In 1967 the University of Chicago professor unveiled his framework for thinking about the so-called natural rate of unemployment, which posited that if policymakers used monetary and fiscal stimulus to push the unemployment rate below its natural level, inflation would accelerate without bound. The inflationary decade that followed cemented its influence.

Democratic administrations in the postwar period still saw a role for fiscal policy in securing and preserving full employment, even if it wasn’t mandated by law, and invested in worker training and job creation programs like the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act of 1973, which at its peak minted 725,000 -public-sector jobs in a single year.

In the mid-1970s, in response to rising unemployment that was especially afflicting minority communities, liberal Democrats—building on the work of civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr., who advocated a job guarantee—tried once more to institutionalize the role of the federal government as an employer of last resort. But the economic experts, including those in President Jimmy Carter’s own administration, pushed back, and the effort was once again defeated. The so-called Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act that finally emerged from the process in 1978 did, however, instruct the Fed to work jointly with the White House and Congress to ensure “full employment” and “reasonable price stability,” which is how the dual mandate came into being.

In practice, the Fed has mostly prioritized reasonable price stability over full employment. By Friedman’s standard, the U.S. economy operated at full employment two thirds of the time from the end of World War II through the 1970s. But from 1980 to present, it’s been at full employment only about a third of the time, according to Congressional Budget Office estimates of the natural rate of unemployment. “Even though they got the mandate, they basically haven’t run the economy at full employment since they got the mandate,” says Claudia Sahm, an economist who left the Fed last year.

Paul Volcker ushered in the new era shortly after taking over the top job at the central bank in 1979, ultimately taming double-digit inflation by raising interest rates to record levels, though at the cost of triggering recessions that pushed unemployment to the highest it had been since the Great Depression. Today’s Fed leadership came of age during the so-called Volcker shock and the key lesson they took away from the experience was that it’s imperative to act early to keep price pressures from spiraling out of control.

That mindset was in evidence in 2018, when the Fed’s rate-setting committee voted to hike four times over the course of the year as unemployment dipped below its members’ estimates of the natural rate—even though inflation continued mostly to track below their 2% target. Economic models such as the Phillips curve implied that without tightening credit conditions to restrain hiring, it would only be a matter of time before rising wages began stoking inflation to undesirable levels. Yet by the time of the final hike in December 2018, financial markets were signaling that the slowing global economy couldn’t handle the tightening.

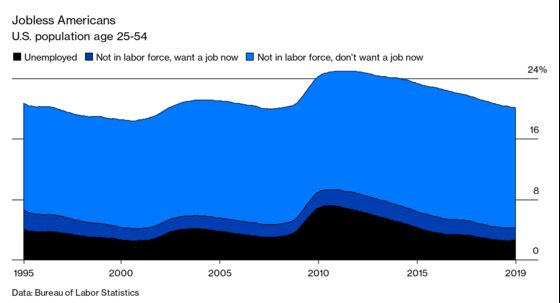

Now, Powell and his colleagues have changed their tune. Unemployment has been below even the most optimistic committee members’ estimates of the natural rate for much of the last three years, and inflation has yet to show signs of accelerating. Part of the problem, says Sahm, who’s now director for macroeconomic policy at the Center for Equitable Growth, a Washington, D.C. think tank, was too much focus on the unemployment rate, which only counts jobless individuals actively looking for work, and not persons who would like a job but have been discouraged from looking for various reasons, including poor job prospects.

Even incorporating the discouraged jobless into the calculation may not be enough. Since 2015 the biggest factor in measuring employment gains among individuals aged 25 to 54 has been not those counted as unemployed or as discouraged, but those who say they aren’t looking for work. While that number has been coming down rapidly, the proportion of prime-working age individuals who aren’t working because they say they don’t want a job still stands at 15.9%. That’s well above the 1995-2007 average of 14.7%, which suggests there is still more slack in the labor market.

Despite the endless stream of news about the hot job market, like Taco Bell’s announcement this month that it would test raising salaries for managers to $100,000 at some of its locations, there’s evidence that inflationary risk from the low unemployment rate may be in fact diminishing. Wage growth—which arrived late in the economic expansion and hasn’t exactly been gangbusters—is showing signs of flagging. Average hourly earnings advanced 2.9% in 2019, according to the Labor Department, well below the 3.3% pace in 2018.

At his regular press conference following the FOMC’s most recent policy meeting on Dec. 11, Powell conceded that the data weren’t consistent with the hallmarks of a fully-employed economy. “I’d like to say the labor market is strong. I don’t really want to say that it’s tight,” he told reporters. “I don’t know that it’s tight, because you’re not seeing wage increases.” (This is part of the reason the Fed has signaled it will probably leave rates unchanged at least through the end of 2020.)

Yet people like Sam Bell, who runs Employ America—a Washington-based organization lobbying for low interest rates—are wondering whether the change of heart on unemployment will stick in the event that the global economy begins picking up steam, lifting U.S. growth. “I think he wants to tell this labor market story, but it’s also a convenient confluence of events that allows him to really lean into it,” says Bell, whose own conception of full employment is closer to Beveridge’s ideal. “What we say on our website is more employment, higher wages, better-quality jobs. We’re far from better quality and higher wages.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net, Margaret Collins "Peggy"

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.