Inflation Jeopardizes the Fed’s Goal for Inclusive Employment

Inflation Jeopardizes the Fed’s Goal for Inclusive Employment

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- “Broad-based and inclusive.” That’s how officials at the Federal Reserve have taken to describing the maximum employment mandate Congress handed the central bank in 1977. The addition of those modifiers is a shift that came about as part of a 20-month review of the Fed’s monetary policy framework that culminated last summer against the backdrop of a national reckoning on race sparked by the killing of George Floyd.

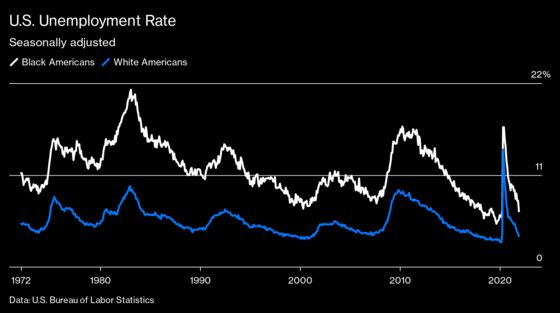

The idea is that economic indicators such as the Black unemployment rate will now be incorporated into assessments of whether or not the U.S. has reached maximum employment. There’s a lot riding on this reconceptualization because Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues have repeatedly stated that getting there is a prerequisite for higher interest rates.

Now, with inflation dominating the conversation in Washington, those inside and outside the Fed trying to keep broad-based and inclusive employment at the top of the central bank’s agenda for 2022 are facing an uphill battle.

Consumer prices rose 6.8% in the 12 months through November, marking the fastest pace of increase in almost 40 years. Most forecasters expect inflation to moderate in 2022, but Fed officials are still sweating.

After all, they have to balance two mandates: maximum employment and price stability. The latter is becoming an increasingly divisive issue ahead of next year’s midterm elections, with Democrats as well as Republicans pressuring Powell, who just won renomination from President Joe Biden to another four-year term at the helm, to do something about it. Recent comments by Powell and other Fed policymakers suggest they are poised to move up the timeline for interest-rate increases when they meet this week.

The jobs problem is losing some political salience, which may facilitate their pivot. The economy is rebounding strongly, and the unemployment rate fell to 4.2% last month, still above the 3.5% rate that prevailed before the pandemic, but way down from the peak of 14.8% in April 2020.

Beneath the 4.2% headline figure lie some persistent gaps: In November the White unemployment rate was 3.7% while the Black unemployment rate was 6.7%. For some, this is evidence that the central bank’s work isn’t done.

“There are still enormous disparities in health, in labor force participation, in all of these metrics,” says Prabal Chakrabarti, who as head of the Boston Fed’s community affairs department had a hand in organizing a series of conferences that convened experts to discuss possible remedies to structural inequities in areas like health care and criminal justice that fall outside the central bank’s direct purview. “So, I think the case is still there, and so long as we’re missing on the mandate, I think we’re obliged to continue the momentum.”

When asked during a Nov. 3 press conference after the Fed’s most recent policy meeting whether he thought the U.S. could reach maximum employment by the second half of 2022, Powell called it a “plausible” outcome, while stressing that there was still “ground to cover.”

He and other Fed policymakers have resisted efforts to pin down what “broad-based and inclusive” means in practice. Would the unemployment rates that prevailed in February 2020, on the eve of the pandemic—6% for Black Americans and 3% for White Americans—meet the test? Or do the unemployment rates need to be equal? Is the answer somewhere in between?

Those are politically charged questions, argues Darrick Hamilton, an economics professor and founding director of the Institute for the Study of Race, Stratification and Political Economy at the New School in New York. Civil rights activists including Coretta Scott King were the ones who, in the 1970s, led the fight to have the employment mandate enshrined in law in the first place.

From 1972, when the Labor Department began publishing monthly data on Black unemployment, to 2020, the Black unemployment rate fluctuated between 1.8 and 2.6 times the White unemployment rate.

The typical pattern has been one in which the ratio narrows in recessions, as Black and White Americans alike lose jobs, before widening again in the early stages of the ensuing expansions, as White Americans are hired back first. It’s only later, as the labor market tightens, that the gap begins to shrink again.

So far, that pattern has repeated during the pandemic: In April 2020, the ratio of Black to White unemployment collapsed to a record-low 1.2, but as of last month, it was back at 1.8.

How much more could the Black-White unemployment gap narrow if the economy were allowed to run hot for longer? That’s a matter of some debate. At a press conference in September, Powell expressed the view that factors beyond the scope of monetary policy, such as disparities in education, were at play.

Hamilton and others—like Dorian Warren, a political scientist and organizer—disagree with that emphasis. As evidence, they point to the fact that the gap persists, and in some cases widens, as one travels up the education ladder. For instance, the disparity in unemployment rates between Black and White Americans with four-year degrees is actually larger than between those with two-year degrees.

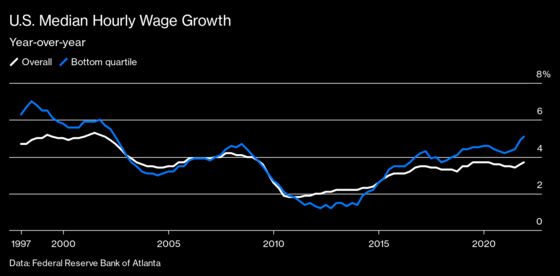

Instead, Hamilton and Warren point to the deeply racialized structure of the American job market. This, they argue, has persisted thanks to decades of fiscal and monetary policies that have kept aggregate demand below levels which would force employers to first hire, then promote, non-White individuals.

“Once you get hired in a workplace, what kinds of jobs are you channeled into? This is, I think, made most visible if you think of the restaurant industry, or hotels, where you think of front-of-the-house jobs vs. back-of-the-house jobs,” Warren, who is president of Community Change and co-chair of the Economic Security Project, says.

“If you’re Black or if you’re an immigrant, you are much more likely to be channeled into back-of-the-house jobs, if you get hired. So you are going to be in the kitchen, vs. a host or hostess.”

David Wilcox, director of U.S. economic research at Bloomberg Economics, says Fed officials in the next few months could declare that with the quits rate at an all-time high, households reporting in surveys that jobs are plentiful, and wages rising, the labor force must be fully employed.

That could be used to justify a decision to begin raising rates well before the gap between Black and White unemployment rates close. And for people like Rakeen Mabud, the chief economist at the Groundwork Collaborative, a progressive think tank in Washington, it would call into question the central bank’s much-lauded shift in 2020.

“The story that we’re seeing bubble up around inflation is one that is designed to lean into a deeply austerian world, one that does bake in and sustain huge amounts of inequality,” Mabud says.

“A real commitment from the Fed, and from policymakers across the monetary and fiscal space, to a truly equitable recovery means really keeping an eye and a real focus on that Black unemployment rate—and until that is down at par with what every other worker in the economy is facing, we’re not done.”

Read next: This Is Jerome Powell’s Shot at a Volcker Moment—in Reverse

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.