Fear and Driving in Los Angeles: The Trip That Changed My Life

Fear and Driving in Los Angeles: The Trip That Changed My Life

(Bloomberg) -- The day I turned 16, I proudly strode into the local DMV, radiating all the poise of the confident young woman I had just become, and took my driving test. I failed.

A week later, slightly less poised, I returned. The examiner told me before I even turned the car on that I had not checked my side mirrors. I didn’t tell him I didn’t actually know what the side mirror was for, except to practice flattering facial angles. Anyway, I failed again.

I took the summer off to gather, reflect, and engage in an irresponsible amount of underage drinking because it was a) the ‘90s and b) I was legally prohibited from acting as a designated driver. Then I went to an semi-rural DMV office where they were known not to ask too many questions or ask you to do anything hard, such as parallel park. Or make left turns. Or speed up. Or slow down.

I passed. The following day, giddy with a sense of unbridled freedom that seems impossible now, I backed out the 1985 Toyota Camry my grandfather had reluctantly relinquished to me months earlier—harvest gold and still smelling of a spilled bottle of Old Spice—from my parents’ driveway. I picked up my friend Ellen, and promptly got into a head-on collision with another vehicle.

The sun had blinded me from noticing that the light had turned red; I also didn’t realize that the driver’s side sun visor served a purpose beyond holding yet another convenient mirror in which one could touch up one’s mascara and further practice flattering facial angles. No one was seriously injured and both cars were still more or less drivable, but the takeaway was clear: I genuinely could not drive.

A feeling of clammy terror would descend on me from the moment I turned the car on until I unsteadily pulled into the most remote possible parking space, wherever I was going. My hands shook. My heart raced. Changing lanes filled me with adrenaline-laced dread, as if I were about throw myself out of a burning building. I’d check for an opening and recheck again and again until I had to slam on the brakes to avoid rear-ending the car in front of me that I had forgotten was there.

The whole experience was so unpleasant that I began driving less and less. By the time I went away to college in New York, it had been months since I had bothered to get behind the wheel.

New York was a relief. Not only was driving not a thing you had to do, it was almost a badge of honor not to. New Yorkers, it seemed to me, manage the constant overstimulation of their environment by taking to heart Coco Chanel’s maxim of elegance as refusal: They assert their intellectual and cultural superiority by proudly declaring what they don’t do. “I don’t cook.” “I don’t go above (or below) 14th Street.” “I don’t drive.”

It was an ethos I wrapped around myself as tightly as a pashmina on a chilly night. I kept wrapping myself in it for a decade and a half, long after it got kind of ratty. (Nobody really wore pashminas, anyway, but there wasn’t much I could do about it because I couldn’t afford anything new.)

Like many New Yorkers with pretensions of elegance, years of living in tiny, exorbitantly expensive apartments with kitchens incapable of producing even the simplest of meals (not that I knew how to cook one) had left me flat broke and morbidly depressed. I had been in New York for 15 years, and I couldn’t imagine this changing if I stayed where I was.

On the other side of the country, promise beckoned. Over the years, I had amassed a small body of plays and books and articles—and mostly, television recaps—and that work, specifically the television recaps, had started to get me invitations to “take meetings” in Los Angeles.

It was before ride-sharing was a thing, so for me, in my non-ambulatory state, this meant flying myself out to L.A., begging or bribing a friend or my sister to come pick me up, then further begging/bribing them to drop me off at a plush office building or studio lot.

There, I would sit on a fancy couch, be offered cappuccino and tiny bottles of water by assistants and generally treated, however falsely, as if I were a Person Who Mattered, until I was ushered in to meet an executive for a “general meeting.” That’s when you get to spend an entire hour talking about yourself to someone looking to be entertained, sort of a cross between a first date and a therapy session.

In general—pardon the pun—these meetings went very well (although, pro tip: It’s almost impossible for them to go badly) and would universally end in some version of an exuberant hug and an “Oh my God, you’re so great! We love you! Let us know when you move to L.A.!”

I’d strut out of the building as if I owned the place and then stand on the sidewalk, feeling my confidence ebb under the suspicious glare of the security guards as the ride I had arranged or the cab I had called failed to show, reminding me why I couldn’t move—could never move and had no future—unless I could somehow grab a steering wheel and drive there.

I don’t quite remember how many trips it took (five or six?) before I finally decided to bite the bullet and just rent a car. It had been at least 10 years, probably more, since I had actually driven one, but I still had a valid license, a record wiped clean by traffic school, and a credit card.

It felt like a huge decision, but every so often that happens in life. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid had to jump off the cliff to escape (and die.) Thelma and Louise had to drive off a cliff to escape (and die.)

To escape, I had to rent a car at an airport discount car rental place.

I was startled at how straightforward the whole process was, how the woman at the Enterpise counter handed me the keys without so much as a second glance. Didn’t she know who I was? What I was capable—or rather, incapable, of? This was a suicide mission, and while I was mostly resigned to the inescapable fact of my own imminent death, I was really, really hoping I wouldn’t kill anybody else.

I got in the car. I started the car. I began the drive from LAX to my friend’s house in Altadena, which as I was about to learn, is a very long way. I think it was raining, and the windshield was blurry, although that might have just been my panic tears.

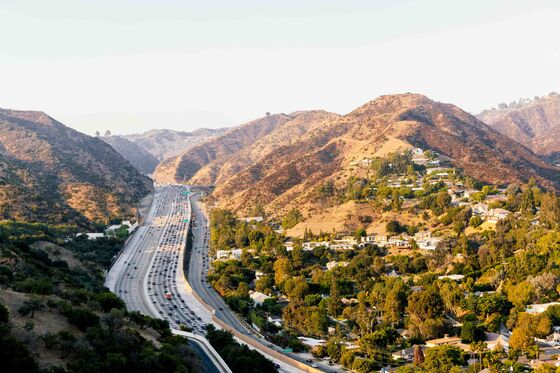

I slowly—dangerously slowly—merged onto Interstate 405 (I think) as though I were ascending the stairs to the gallows. Squeezed into a tunnel in the darkness somewhere on IS 10, I suddenly found myself thinking of Princess Diana in her last moments. She had died around the same time I had started driving. Was that the source of my phobia? Had Diana been afraid? Did she know what was about to happen?

And then, like a flash of light, it hit me (not literally): This was why I was a bad driver. I had disappeared into ghoulish roleplay when all I needed to do was drive. It was that simple—and that impossible. Every lane change was merely a lane change, not an insurmountable obstacle, merely a change of position. I was expending so much mental energy in experiencing my phobia of driving. This was energy that could be better used toward actually just doing it.

I would get where I was going or I wouldn’t. But the liminal state of being in the car was temporary, and if I could accept that, I might get to an eventual red light where I could take a pause and reconnect to my breath, my future, and more important, my present.

Connect to the breath. Exist in the moment. I had been in L.A. for an hour, and I had already invented car yoga. Who knew what else I could accomplish? If I could just make it off the freeway.

When I finally pulled into my friend’s driveway, I had the kind of full body muscle shakes you get after a workout you thought you couldn’t complete. I was also triumphant, bathed in endorphins. I had made it. I had driven, I had beaten death—and the more challenging 405. I had never felt so alive.

The week ahead posed problems. I entered a meeting in Burbank sobbing, trying to explain something that had happened on the road. They asked if I had gotten into an accident. “No,” I said, “I accidentally got on the 101.” (They never called me back.) A teamster screamed at me from the cab of his truck when I couldn’t get into a parking space and was blocking the entire street. When I said I was from New York, he immediately jumped out and parked my car himself.

But one night, it all clicked. I went to drinks with a friend in Santa Monica, and drove back east at midnight on a shockingly empty stretch of road. There were stars and mountains. I sped. I sang. I could go anywhere. It took 35 minutes to go 30 miles, and I have never felt so free.

Six months later, I moved.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.