From Lethal Viruses to Insect Sex, Farmers Use Bugs to Kill Bugs

From Lethal Viruses to Insect Sex, Farmers Use Bugs to Kill Bugs

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For decades, Adam Baldwin’s family used chemicals with multisyllabic names to keep caterpillars such as earworms and podworms from chomping their corn, soybeans, and sorghum. While the pesticides were generally effective in getting rid of the hungry invaders, they also killed beneficial insects such as ladybugs, which help control aphids that cover crops in a gooey residue and reduce yields. So for the past two years, Baldwin, a fifth-generation farmer in McPherson County, Kan., has used a lab-grown virus that takes out the caterpillars while leaving other bugs alone. “It’s very specific to the one insect, a safe product,” he says. “It killed what we were going after, but it didn’t kill what we weren’t.”

Baldwin uses Heligen, a natural virus harvested from infected caterpillars that’s sprayed on crops at the first sign of infestation. The virus spreads among the bugs, and each infected insect becomes a source of infection for others, giving further protection to the crop as it passes from generation to generation. “Once the caterpillars feed on the virus, they die and liquefy and release billions of new virus particles,” says Peter Berweger, chief executive officer of AgBiTech Pty Ltd., the company that makes Heligen.

The virus is one of a growing number of tools that provide natural protection for crops, ranging from bacteria to insect sex pheromones to substances derived from spider venom. Global sales of such products will double to $10 billion annually by 2025, researcher DunhamTrimmer LLC predicts. While that’s a fraction of the $61 billion farmers will spend on agrochemical crop treatments in 2020, alternatives are gaining traction with investors. Biological crop protection startups drew $184 million in venture capital last year, up fivefold from 2018, researcher PitchBook estimates. “New companies are emerging in the space almost monthly,” says DunhamTrimmer managing partner Mark Trimmer.

Giants of the crop protection business are also taking note. The venture capital unit of BASF SE has invested in Provivi Inc., which sells pheromones that disrupt mating by making it harder for insects to find one another. Bayer AG, which is developing technologies focused on microbes that can protect plants from diseases and pests and help them better absorb nutrients, is also teaming with Joyn Bio LLC to explore probiotics, beneficial bacteria that can improve crop yields and reduce chemical fertilizers. And Syngenta AG has put money into 15 startups in the sector in the past decade. “The science that’s happening in this space is pretty extraordinary,” says Corey Huck, who heads Syngenta’s biological crop protection business.

Pests, fungi, and weeds reduce crop yields by as much as 40% globally, costing $1.4 trillion a year, according to CABI, an English nonprofit that researches agriculture. The damage is growing as many insects develop resistance to established treatments, which spurs farmers to spray even more chemicals on their fields. That in turn causes a litany of concerns about the environmental toll and safety of compounds such as Bayer’s weedkiller Roundup, which is the subject of more than 40,000 lawsuits alleging it causes cancer. Advocates say biopesticides are safer than conventional methods because they target individual species, and they’re likely to be permitted under regulations governing organic produce, allowing farmers who use them to sell their harvests at a premium. “Consumers want it and innovators see a path to market, so growth is inevitable,” says Rob Dongoski, agribusiness leader at Ernst & Young LLP.

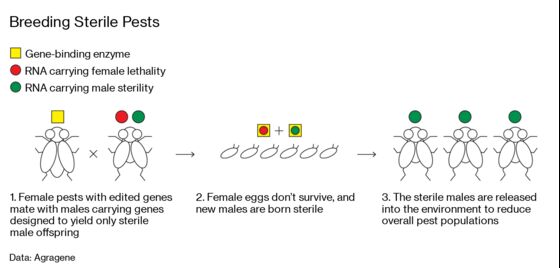

At least 200 companies sell biopesticides, researcher Mordor Intelligence estimates. AgBiTech has seven virus products aimed at fighting bugs that attack dozens of plant species. Vestaron Corp. makes insecticides based on spider venom to fight bugs that infest fruits and vegetables in greenhouses. Agragene Inc. is using gene editing to breed sterile male fruit flies for release into orchards or berry fields, where they mate with wild females, which then produce unfertilized eggs. “It’s insect birth control,” says Gordon Alton, Agragene’s CEO. “It’s not an insecticide per se. We prevent them from being born in the first place.”

Still, there are many hurdles to widespread acceptance of biologicals. They can be pricier than traditional pesticides, and they frequently require more attention from users. Farmers must apply them within a relatively tight time window, and since they contain living organisms such as viruses, fungi, or bacteria, they often need refrigeration—a challenge in developing countries. And while the U.S. has simplified licensing, many other countries regulate them like traditional products, which means approval can take years.

Kenyan farmer Kelvin Sauroki is waiting for approval of Fawligen, an AgBiTech virus aimed at controlling fall armyworm, which attacks crops worldwide. Sauroki says farmers he knows have tried to battle the pest with applications of toxins such as battery acid and engine oil. “They’re desperate,” he says. He’s used conventional chemicals, but growing resistance forced him to spray each crop multiple times. Fawligen, by contrast, worked after a single application in a test in November. But Sauroki can’t get more because the Kenyan government has yet to allow its commercial sale—though he hopes that will happen before he plants again in April. “That’s my prayer,” he says. “It’s cheaper, and it’s safe.”

--With assistance from Fabiana Batista.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net, Jeff Muskus

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.