F1’s New Formula Tastes Like Bitter Medicine to Ferrari and Mercedes

F1’s New Formula Tastes Like Bitter Medicine to Ferrari and Mercedes

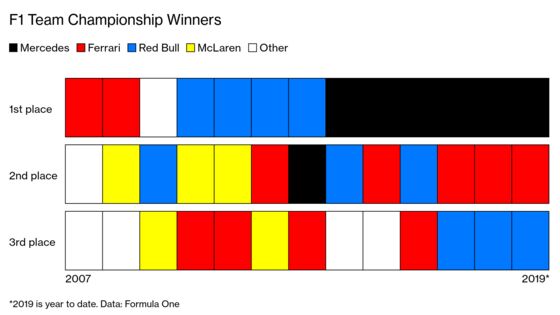

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When the marshal waved the checkered flag at the Azerbaijan Formula One race on April 28, the result came as little surprise: The first car across the line was a Mercedes. The second was, too. In Shanghai two weeks earlier, the outcome was the same. Ditto the other two races this year. That puts Mercedes in pole position to win the 2019 team championship. Just as it did last year. And the four years before that. In fact, only two teams have won the title in the past nine years, and about the only mystery in the competition is which Mercedes driver will come in first, and whether third place will fall to Ferrari or Red Bull.

That predictability has become a headache for John Malone, the Denver billionaire who in 2017 paid $4.4 billion for Formula One. Malone’s Liberty Media Corp. has sought to revive the troubled series by supercharging the competition, but the wealthiest and most powerful teams don’t like the idea. The three leading entrants, at risk of being dethroned, have threatened to pull the plug on their Formula One efforts unless they can shape the rules to their liking. “One of the teams could quit if things go in the wrong direction,” Niki Lauda, a three-time F1 champion and now a part-owner of the Mercedes squad, told Germany’s WirtschaftsWoche last year.

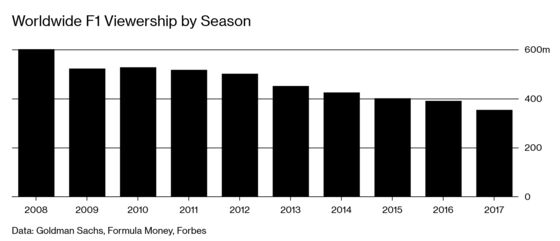

Since its founding in 1950, Formula One has become the world’s most popular motor sport and one of just a handful of truly global competitions, with races in 21 countries this year. But since Liberty took over, F1’s revenue and payments to teams have been flat. Its television audience shrank by two-fifths in the 10 years to 2017, according to Goldman Sachs, and Evercore estimates that the company’s value has dropped about 12 percent on Malone’s watch. “There has to be some degree of cost containment and a more appropriate apportionment of revenue to create a competitive grid,” says Sean Bratches, a former ESPN executive who serves as F1’s commercial operations chief.

The sport’s rulebook, the Concorde Agreement, is renegotiated a couple of times a decade by the dozen or so teams, the management group that Malone bought, and the Fédération Internationale de L’Automobile, which regulates F1 and various other competitions. The current 181-page pact will expire in December 2020, and any rewrite typically must be completed at least 18 months in advance so teams can ensure that their cars adhere to new rules. That means the talks should be wrapping up in time for the season highlight, the storied Grand Prix winding through streets of Monaco on the shores of the Mediterranean on May 26. But negotiations “really have just started,” Mercedes team chief Toto Wolff told reporters on April 12.

Malone wants teams to share prize money more evenly so losers don’t pull out of the circuit or go bankrupt, as dozens have in the past several decades. Liberty’s latest proposal includes spending limits to make races a test of drivers’ skills rather than a battle of the richest engineers—something the richest squads oppose. “The teams at the top don’t want a budget cap because there’s a direct correlation between the amount you spend and how often you win,” says Christian Sylt, head of Formula Money, a sports consulting firm. Another key issue is extra cash granted to the longest-serving teams, which gives Ferrari—a contestant in every series since 1950—a bonus approaching $100 million per season. “The financial regulations are going to be tough,” says Claire Williams of the ROKiT Williams team. “They’re never going to please everybody.”

While only the foolhardy get into F1 to make money—running a team can cost hundreds of millions of dollars a year—most see it as a promotional opportunity, for either an automaker (Renault, Alfa Romeo) or a broader consumer brand such as Red Bull, Virgin, or Vodafone. But it’s hard for marketing bosses to make the case for a competition that’s so lopsided. “We don’t need to be in the sport for cash profit,” says Zak Brown, head of McLaren Racing, whose parent company makes street-legal supercars that can cost more than $1 million. “But we don’t want to have the type of losses we’re currently sustaining and still not be competitive.”

Then there’s the problem with track owners, who pay Liberty tens of millions of dollars per race. Since they don’t get a cut of broadcasting revenue, they must recoup that entirely via sales of tickets that frequently top $500 for grandstand seating at the Sunday final. Britain’s Silverstone, a former airbase in the English Midlands that’s played host to Formula One since 1950, is working under a contract that expires in the coming months and is marketing this summer’s competition as potentially its last. And Germany’s Hockenheimring signed a one-year pact for the current season while it seeks a better deal. “From a financial point of view it has to be affordable,” says Jorn Teske, marketing director at the German track, which has held races since 1970 (after repairing damage from tanks that swept through the region in the final months of World War II). “F1 races can’t be such a risk for promoters.”

Liberty has managed to juice extra cash from the schedule by shifting contracts to pay-TV. That yielded a modest increase in broadcast revenue, but it risks sapping interest in the sport by restricting the audience. Forty percent of fans watch less racing when there are paywalls, according to a 2017 Nielsen survey. Liberty has also said it expects to boost profits with more sponsorships; it has just 10 official global partners, compared with scores for the Professional Golf Association and Nascar. But Liberty Chief Executive Officer Greg Maffei told analysts that’s “proven to be harder and less uptick than we initially thought.”

While Wall Street analysts see substantial upside if Liberty’s changes are instituted, operations boss Bratches says success will depend on remaking an operation that was undermanaged for years before Liberty bought in. Aiming to boost F1’s presence on social media, Bratches had lunch with Lewis Hamilton, the Mercedes driver who’s won the season championship five times. He asked Hamilton why he doesn’t share high-octane clips of races on Facebook or Instagram. The response? Hamilton “basically put down this stack of cease-and-desist letters that the prior management had sent him every time he did.” —With David Hellier

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.