The Woman Who Transformed Bollywood Behind the Scenes

Guneet Amarpreet Kaur Monga believes in miracles.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Guneet Amarpreet Kaur Monga believes in miracles. There is no other way she can make sense of her journey so far. Given the knocks life has dealt her, it is hard to believe that this thirty-four-year-old film producer, with closely cropped hair and large, sparkling eyes framed by a pair of dark-rimmed spectacles, is not bitter. She is serene—so serene, in fact, that it feels like Mumbai, with its frenzied energy and high-decibel noise levels, slows down when Guneet speaks.

Guneet lives by the sea. Outside her window, palm trees sway gently and the Arabian Sea laps at the shore. Gazing at the ocean and breathing the fresh, salty air are important to her—“It’s calming, peaceful and it balances your energy.” Guneet’s ocean-front flat in upscale Juhu is a far cry from a humble childhood spent in an apartment in Surajkund, near Faridabad, which her family rented for 5,000 rupees a month. Each morning, the chants of “Om namah shivay” fill her Mumbai home. “When I wake up in this apartment, I thank the universe,” Guneet says. “I give thanks every day.”

According to Variety, the widely read American film magazine, Guneet is one of fifty women from the entertainment industry doing “extraordinary things on the worldwide stage.” In March 2018, the magazine published its first International Women’s Impact Report, and Guneet was one of only two women from India in it. The other was actor Deepika Padukone.

The introduction to the report said, “Let’s face it: It’s not always easy to be a woman in this world, let alone a showbiz leader that happens to be one. There are the usual leadership obstacles to overcome, plus downright sexism and resistance in certain pockets of the planet. Yet, these women persist.”

Guneet is on the list for her work as a path-breaking female producer in Bollywood, part of a new wave of Indian film-makers making a global impact. Known for backing strong, independent content that sits comfortably between commercial entertainers and the art house world, Guneet has more than thirty films to her name, which include some of the most critically acclaimed movies in contemporary India, such as The Lunchbox, Gangs of Wasseypur and Masaan. Typically, these are low-budget films with strong scripts that focus on edgy, alternative themes. Fundamentally Indian at heart, these indies have universal appeal.

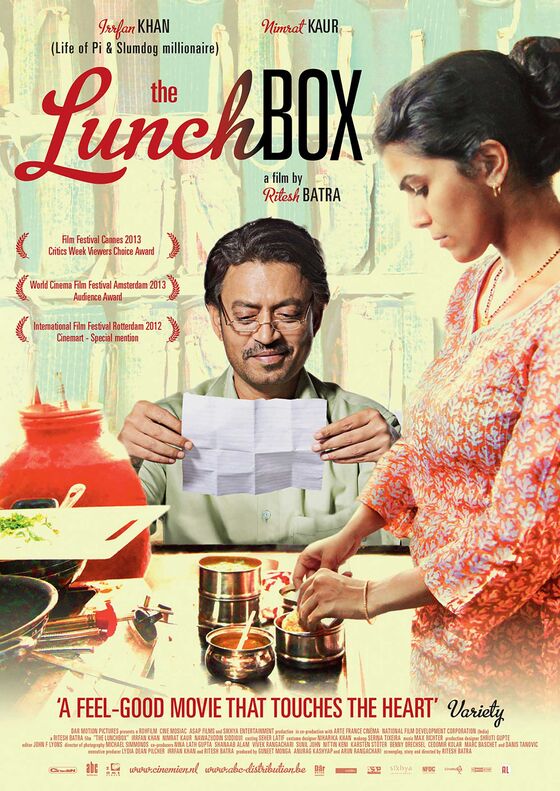

The Lunchbox is Guneet’s jewel in the crown. Simply put, it’s the film that got her noticed and earned her and her co-producers a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) nomination in 2015. The poignant love story, which revolves around a box of food that gets delivered to the wrong person in a Mumbai office, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2013 to a standing ovation. It went on to achieve unprecedented success worldwide—a rare Indian crossover hit. The Guardian gave it four out of five stars and said, “The Lunchbox is perfectly handled and beautifully acted; a quiet storm of banked emotions.” Made on a low budget of Rs 10 crore, or $1.5 million, it became one of the highest-grossing foreign films in the US in 2014, earning $4.2 million.

Of The Lunchbox, Guneet says, “That was the dream—of that one Indian film that goes and sells around the world.” It created history, but that is hardly surprising. Very little about Guneet is formulaic. She is not one to stick to tradition. She breaks it.

“I am a disruptor,” she says, a quiet confidence in her deep voice. It’s hard to find an area in her personal or professional life where she has followed the tried and tested path. “You have to be in the corner and do the work that nobody is doing and make enough noise so that you are noticed,” she insists. The trick is to keep at it.

Born in New Delhi on 21 November 1983, Guneet’s life has been peppered with loss, depression and death. As a young child, she witnessed domestic violence within her home. Her first film bombed spectacularly. Both her parents died within six months of each other. Yet, the head of Sikhya Entertainment, a company she founded in 2008, is not bitter. You won’t hear Guneet complain life has been unfair. She says she has a lot to be grateful for.

That includes no one showing up to watch her first film. Brimming with ambition, Guneet dreamt of moving to Mumbai after studying mass communication in Delhi. She wanted to make films and tell stories. Her first brush with movies—as an intern on the French-German-Indian independent film Valley of Flowers—had her hooked.

Her job involved photocopying and scanning documents, entering phone numbers into a database and doing odd jobs for the production team. It was grunt work, but she loved every minute of it. This stint came after she had tried her hand at umpteen other jobs. By the time she was twenty-one, Guneet had been a DJ, an insurance agent, a sales agent for Laughing Cow cheese, an event planner, a rally car driver and a property saleswoman for her late father. Once she found herself on a movie set, however, she knew there was no going back. Guneet wanted to make a film herself.

Mumbai beckoned. But she needed capital to make the move and a movie. Her neighbour in Delhi, Kamlesh Agarwal, offered to help by investing 50 lakh rupees in her film project. In turn, he suggested Guneet make “cute cute films for children.” Guneet heard him out patiently, then replied, “Uncle, I think it is a very bad idea.” Boldly, she proposed another one instead: why not give her the money so she could move to Mumbai and make a film—on a topic of her choice. It was a big ask. Agarwal relented. He gave her the capital.

“I never doubted her integrity,” he says years later, speaking affectionately and admiringly of Guneet, whom he has known since she was a teenager. “She was honest and sincere in her approach, and it is probably only because of that that I invested money in her. I knew she would never cheat me.”

The aspiring film-maker arrived in India’s heaving film capital with money in her pocket, fire in her belly, but not a clue about where to start. The only thing she knew was that she was going to make a movie. Nothing was going to stop her. She networked and met as many people as she could, convinced someone would have a story worth telling. “I used to meet people in food courts, in malls and say, ‘Mere paas 50 lakh hain, aapke paas story hai?’” She was twenty-one, naive and daring at the same time.

Her persistence paid off. She found a script that excited her. It told the story of four boys with limited resources but an unrivalled passion for cricket. She decided to buy into it through the first production company she founded, Speaking Tree Films. The movie, titled Say Salaam India, released in 2007. It was the kind of film that should have had cricket-mad India going ga-ga.

But fate had a different plan. A few days after the film released, India’s cricket team crashed out of the World Cup in the West Indies. No one foresaw this debacle. Cricket fans were angry. They pelted stones at cricketers’ homes and the media went on the offensive. A feel-good movie about cricket was not going to draw an audience, so cinemas sent the film reels back to Guneet. Her first film had tanked and she was shattered.

That she had let Agarwal down weighed heavily on the producer’s conscience. Guneet had taken his money and watched it go down the drain. Somehow or the other, she would repay him. “I used to keep telling him, if I don’t give your money back, I should not be in this business.” Agarwal didn’t expect to recover the loss. “I invested the money and she was a partner. It was to be shared—profit and loss. I never pushed Guneet to cover her part of the loss.”

But Guneet was already working on plan B. She was sure that someone, somewhere, would want to see the film. She decided to take the movie to a group of people who always get excited by cricket: students. Travelling across small cities and towns in north India, she arranged private screenings in schools, for which she charged a nominal fee. It wasn’t a conventional strategy, but then Guneet is an out-of-the-box thinker. In nine months, she earned enough to pay Agarwal back in full. “I just was so driven to make that money back that I went to the moon and back to try and make that happen.”

Looking back, Guneet says this setback taught her the single most important lesson a film producer needs to learn—that there is an audience for every film. “You just have to find it.” There are ups and downs in business, which Guneet had learnt from her dad, a property consultant.

“My dad was always saying, ‘Business mein yeh hota hai,’ says Guneet. But her parents had also instilled a deep sense of honesty in her. “My mother used to say, ‘Whatever you do, you are answerable to your own conscience.’” Those lessons, of being honest and having a clear conscience, drove her to pay Agarwal back.

Guneet slows down when talking about her parents. It brings back painful memories of her mother suffering years of abuse and domestic violence at the hands of her father’s family.

Witnessing that violence as a young child left Guneet with a fear of loud voices and a deep intolerance for injustice. She cannot bear to listen to anyone scream and she rarely raises her voice. Loud sounds transport her back to her childhood, when the Mongas lived in a sprawling family home in New Delhi’s Greater Kailash where she saw her mother being verbally and physically abused. One night, when Guneet was twelve, the violence almost claimed her mother’s life. “They tried to set fire to my mom in front of me. There was police in the house, people holding me.

“It was crazy,” she shudders. That night, her parents fled and moved into a small rented apartment in what was then far-off Surajkund in south Delhi. Guneet has refrained from speaking publicly about her childhood trauma. Sadly, her mother passed away in 2008 from cancer, and within a few months, her father succumbed to a kidney disease. Guneet was twenty-four. Barring one paternal aunt, she has no extended family and no siblings. This void is filled by her friends.

“She savours friendships and likes to keep her friends close” says Mayank Jha, who lived in the same township, Charmwood Village in Surajkund, where Guneet spent her teenage years. The gated community lives up to its cheery name—it has a few villas, a high-rise, a pond and lots of parks. After moving there, Guneet felt safe and peaceful for the first time. She was surrounded by friends her age and was part of a community.

She says they were the best years of her life.

“Looking back, I can connect the dots now,” Mayank says. “Guneet was a really good storyteller. She was always very animated and talkative, and would get emotionally involved when telling a story. Let’s just say, she was dramatic!” Despite her flair for drama, none of her friends guessed she would end up with a career in films. Today, a group of her school, college and Surajkund friends are her most loyal supporters. She considers them her family.

“It’s a two-way street. Guneet gives as much as she takes from her relationships,’ says her childhood friend, Prerna Saigal. Both girls were together from nursery through grade 12 at Blue Bells School in Delhi.

“She’s very loyal,” Prerna says. “Once, we were playing a basketball match in school and I got badly bruised. Guneet came running from the other side of the court, snatched the ball, handed it to me and said, ‘Prerna, yeh leh.’” She did that so her friend could have a go at dunking the ball into the basket. “At that moment, something clicked,” Prerna says. “I knew she was in my corner, I knew we would be friends for a long, long time.”

She was right. Prerna and Guneet developed such a close bond that Prerna says Guneet’s parents were like a second mother and father to her. When they passed away, it was brutal. “I remember that phone call at 3 a.m. when Uncle died. It was the worst phone call to get. I cried it out. But Guneet did not. I kept telling my other friends, she’s not crying, she’s not crying. She was so young but grew up overnight.”

For the next five years, Guneet battled her emotions and endured many dark days before she was introduced to the teachings of Nirmal Singhji Maharaj, better known as Guruji, a spiritual leader. Though he passed away in 2007, millions of devout followers around the world continue to worship him. They believe, as Guneet does, that he delivers miracles. He is said to have cured people of diseases, eliminated pain and shown devotees a way out of suffering. He quickly became an important part of Guneet’s life. She says he transformed her.

A large portrait of Guruji sits on a table in her home in a sea-facing room which has been converted into a temple. Fairy lights are strung across the windows. At night, the little bulbs make the room glow. The focus of the room is a large, plush chair, enveloped by a decorative cream tent suspended from the ceiling. A pair of juttis, bedecked with flowers, is placed at the foot of the chair. No one sits on it—this is how the faithful mark Guruji’s presence. “It is his durbar,” Guneet says. Any of Guruji’s followers can drop in and pray. Satsangs are held here. Guruji’s disciples do seva in this space—they once sat on the floor with bowls and knives and peeled 16 kilograms of carrots to prepare halwa. For Guruji’s worshippers, this room is a sanctuary.

“We all know there is some higher energy and we define it in different forms. I feel very blessed that I found a face to put to that energy,” Guneet says. She wears a locket with Guruji’s picture at all times. Faith is a central pillar of Guneet’s life. Born a Sikh, her earliest memories revolve around family visits to a gurudwara in Delhi. That’s where the Mongas would usher in the new year, every year. Guneet would look forward to it and savour the 31 December service at the Gurudwara Bangla Sahib in Connaught Place.

The festivities would start at 11.30 p.m. with music—dholaks, tablas and 10,000 people chanting Wahe Guru, a Sikh mantra to invoke the Almighty. As it approached midnight, the musicians would drop an instrument from the orchestra, one at a time, till the only sound left was that of voices chanting Wahe Guru, Wahe Guru. It created an intense, emotional vibration in the hall. “It was magical. I didn’t know how to define it but as a young child, I felt extremely elevated, extremely connected. I was overwhelmed and I would be crying.”

Years later, she found herself desperate to feel that way again.

It was 2014. Following the success of The Lunchbox, which she coproduced with her mentor and boss Anurag Kashyap and entrepreneur Arun Rangachari, Guneet hit rock bottom. “Outwardly, the world was congratulating me for the success of The Lunchbox. Inwardly, I was dying.”

She had lost her parents, had not given herself a chance to grieve, had five unreleased films under her name and was out of a job—a job she had thrown herself into. Guneet had been the CEO of Anurag Kashyap Films Pvt. Ltd (AKFPL) for four years when Kashyap took a sudden decision to shut it down.

That decision felt personal. “I was so invested in it, it was like taking something away from me. It did hurt me deeply.” Guneet, who used to work till 4 a.m. and return to office at 9 a.m., was left with a gaping hole in her life. She felt lonely. “Because of Anurag, I did not really address the loss of my parents because he took that position. He was the protector, the father, the mentor.” Losing her job and her role model left her feeling bereft. Guneet says she felt like a failure. “I felt like I was not good enough. It was one-and-a-half years of complete disillusionment. I wasn’t ready to start my own venture and I didn’t know how it would fare.”

Distraught, she visited several gurudwaras in search of one that had the same spiritual energy she would experience during her childhood New Year’s Eves. Nothing came close, till her aunt took her to a satsang in Guruji’s ashram in New Delhi. At once, it felt right.

Guneet asked Guruji for help. She asked him to help her get out of debt for a loan she had taken for a film she was working on, called Tigers. It was sorted out within a week. It felt like a miracle. “But it’s not transactional,” she explains of her relationship with the divine power. “I attribute it to the simple funda of asking the universe, and it shall be done. We have to ask. I have been able to do a lot because I have been fearless in asking. And as you keep asking, your needs keep reducing. I have learnt to ask for the right things.” Her face cracks into a smile. “Initially, you start when you want material things and then you ask for other things, and the evolution of life happens.”

Guneet felt a strong, spiritual connection with Guruji and a deep belief he would look after her. In the months that followed, she travelled across the world looking for answers. “It was like, why me? All my friends have normal lives, a structure, parents.” She was lonely and missed her parents. “You just want those eyes to look at you and say I am happy for you.” She visited ashrams, tried Ayurveda to address health issues, learnt the martial art of Kalaripayattu in Pondicherry and even shaved her head. “I was super depressed and was totally disillusioned. I used to have suicidal thoughts—I hated myself, I hated the way I looked and I specifically hated my hair.” Going bald was her way of running away from her identity.

“Depression is how you feel about yourself. You don’t have control over it.” She believes Guruji nursed her back to health. She began visiting his ashram regularly and engaged with his followers. Over a period of time, she started to feel she was regaining a family. She developed a sense of belonging. The darkness began to lift. And slowly, very slowly, she clawed her way out of the illness. “It was a slow process of self-empowerment,” she says, describing it as a huge personal victory.

Today, Guneet is at peace and appears content. She is working on multiple film projects under her own banner, Sikhya Entertainment. Sikhya is a Punjabi word that means “to keep learning,” and Guneet is invigorated by her work. “I missed that. I missed being inspired. And now I pray: ‘Keep me inspired every day.’”

Guneet’s goal is to produce content that can find an audience between India and the US. Specifically, English-language films set in India that resonate globally—along the lines of the biographical film Lion or Ang Lee’s multiple Academy Award–winning Life of Pi. Most of the films she has produced under the Anurag Kashyap banner AKFPL or her own company, Sikhya, have had alternative content that challenge the song-and-dance stereotype typically associated with Bollywood.

That Girl in Yellow Boots (2011), for instance, is an Indian thriller that exposes corruption, incest and desperation within Mumbai’s seedy underworld. Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) is a gritty, realistic crime movie based on the coal mafia. Peddlers (2012) tells the story of two young men who fall into Mumbai’s drug trade. Haraamkhor (2015) tells a forbidden love story between a teacher and his student. Masaan (2015) is a powerful, dark film about caste, death, love and desire.

The sheer diversity of these stories reflects the churn taking place in modern, aspirational India. These films depict the underbelly of the slice of contemporary life stories which you don’t see in commercial entertainers. Gripping storylines that are neatly packed, they are a refreshing antidote to the predictable glitz and glamour of star-led films Bollywood has dished out for decades.

Today, there are enough takers for the kind of content Guneet backs. Since the first multiplex arrived in India in 1997, it has allowed audiences to develop broader, more sophisticated tastes and given independent filmmakers an outlet for their work, encouraging them to take greater risks with their plots.

“Multiplexes started the conversation about showing more films, yes,” Guneet says. “They helped to create a larger market, but the problem is, films are not shown for long enough.” That’s true for the big blockbusters as well as the small indies. There just aren’t enough screens. According to the research firm ICRA, India currently has around 2,200 multiplex screens. But the country needs many more. Home to the world’s most prolific movie industry and a gargantuan population, India currently only has six screens per million people, compared to 23 per million in China and 126 per million in the US.

Is it necessary for Guneet’s film to send a message? It is starting to feel important, she agrees, because she feels a responsibility towards the public that comes to the cinema, unconsciously looking for answers. Over a raw salad at her favourite Los Angeles restaurant during a business trip to the United States, she says, “I almost feel like, what are we doing with people’s time, people’s money?” If they choose to spend their money on a movie, this avant-garde producer wants them to feel it was worth it.

She works on instinct. If a story moves her, she does what it takes to produce it, even if people warn her that it may not be financially viable. Funding for independent film-makers remains a challenge in India. The Central government does not provide any tax breaks or significant grants for Hindi cinema. The Lunchbox got half of its funding from India, the rest came from France and Germany.

Guneet’s film Monsoon Shootout (2013), a cops-and-gangsters thriller, is another example of an international co-production. It was funded by money from France and the Netherlands. When it got held up due to a shortage of money, she sold the only property her family owned, which was a house in Delhi she had built for her mother. When she needed funds to make Haraamkhor (2012) and Peddlers (2011), she turned to social media and crowd-funded the projects via Facebook. She is an out-and-out doer.

When That Girl in Yellow Boots was selected for the Sixty-seventh Venice Film Festival in 2010, Guneet and team arrived in Italy with more than a hundred posters and 1,000 postcards that cost an arm and a leg in excess baggage. They were ready to make a splash. She had no idea that sites for posters had to be bought months in advance, were expensive and that there were no spots left. Guneet was perplexed. “I said, ‘I come from India, where we put posters on a wall.’ I had come armed with scissors and tape to do the job!” she says with a laugh. She visited cafes, hot dog stalls, pizzerias and begged the managers: could you please put up my poster? She went to Venice’s famous squares where people were eating and dropped a bunch of postcards there. She had a film to sell, she needed to publicize it. Guneet being Guneet, she ended up sticking the posters on the only free space she could find: her friends’ and colleagues’ T-shirts!

She was inexperienced and out of her depth. After the film was screened, Guneet stood in the theatre and waited for people to come up to her to buy the movie. No one did. “Nobody spoke to me and I thought, what is going on?” Exasperated, she went to the then director of the festival, Marco Mueller, and asked him, “Where are the buyers? Why are they not buying our film? We’ve been selected, right?”

Once again, she was reminded how unprepared she was. Mueller told her that producers were expected to set up meetings with buyers months before they met at a festival. “I said, ‘You should have told me!’” Mueller gave her the market book—a massive tome of around 1,500 pages—that listed all the festival attendees. With that, he offered her a word of advice. “‘Meet as many of these people as you can,’ he said, ‘and give yourself three years to do it.’”

Guneet took that advice to heart. She travelled the world to understand the international market. She went to France, the UK, the US. She slept on people’s couches. She met buyers, producers, sales agents, distributors, studios. She showed them her movies. She learnt how festivals work. She networked and made contacts. And in her trademark style, she took chances.

One day, as the sun shone over the New York skyline, she walked in, without an appointment, to the Manhattan offices of Sony Pictures Classics, which distributes, produces and acquires independent films globally. She pleaded with the executives there, “Please can you see my film? Please can you see Yellow Boots?”

A month later, she got a call back. Executives had viewed it and were ready with their feedback. They apologized that they were not ready to buy it. Guneet didn’t mind. She had made a contact and started a relationship. Years later, it bore fruit. When Guneet was shopping around for a US partner for The Lunchbox, Sony Pictures Classics acquired it.

This is not a woman who gives up, Prerna says of her childhood friend. She remembers when Guneet needed to get something signed by Irrfan Khan. Prerna teased her and said, “What about signing Aamir Khan?” To which Guneet replied, “If I get a chance, I will!” “What if he says no?” Prerna asked her. Guneet replied. “But what if he says yes?”

With that attitude and chutzpah, Guneet became a regular on the international film festival circuit, developing an enviable Rolodex of international sales contacts. She quickly gained a reputation as a link between the Indian and Western markets.

Noted author, editor and film critic Baradwaj Rangan of filmcompanion.com says, “Most of the people who work inside India don’t have that kind of network outside the country.” Because of her extensive networking, Guneet has made impressive contacts within film studios around the world. “At the end of the day, festivals and other people latch on to one person and depend on that one person to provide the gateway to that particular film-making community because programmers cannot keep track of every single movement in every single country. Guneet helped to create the bridge between Indian independent films and foreign distributors.”

Gaining credibility did not come easily. Age and gender were not on Guneet’s side. She has a youthful face. During the early years of her career, she would colour her hair grey and wear a sari to meetings. “Otherwise, how would a twenty-six-year-old be taken seriously? I just had to fake it—that I know my shit.” She was often turned away by marketing heads, CEOs and CFOs of companies who had little patience to listen to a young woman peddling stories.

Would they have listened to her if she were a man? “Maybe,” she says, but adds that the discrimination she faced was driven more by age than gender.

Is Bollywood still a boys’ club? She pauses before answering, “There are a lot of boys.” Then pauses again. “I have grown to realize that it is a boys’ club. I am not a man. I don’t smoke. I have always envied people who go on smoking breaks—so many deals are closed out there.” But she also believes that some men within the film industry are champions of gender equality. The fact that the number of women in the film industry is growing is partly because of supportive men, she says.

“Look at Anurag, he would put me in front of the line each time.” Guneet says she often sees people get intimidated by a woman in a position of authority. “I think there is a generation of boys that has grown up feeling entitled to their privilege. They are not ready for an independent Indian woman. They have seen women around them serving and being there for their needs. Suddenly, when they grow up and meet women who don’t do that, they don’t know how to deal with it.”

This independent film producer has her eyes firmly set on an Oscar.

“The universe is conspiring. I believe it will guide me to a path and make me work for it.” Could she become the first Indian producer to bring home the coveted golden statue? Guneet, the woman who believes in miracles, says, “It’s on its way.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Silvia Killingsworth at skillingswo2@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.