Even the Good News Is Bad for Ukraine’s President Zelenskiy

Even the Good News Is Bad for Ukraine’s President Zelenskiy

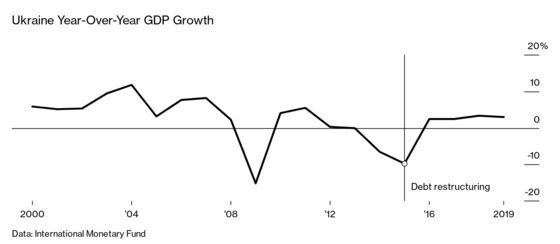

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskiy is battling Russian-backed rebels in the east. He’s trying to zigzag around Donald Trump’s impeachment drama. Even what should pass for good news, the country’s flourishing economy, has a catch: The stronger Ukraine’s economic growth, the more an obscure debt derivative could punch a hole in its finances.

The source of that trouble is a financial instrument that Ukraine granted in 2015 as it teetered on default. To compensate creditors who agreed to write off part of the country’s debt, the government granted so-called GDP warrants that promise future payoffs tied to the country’s annual gross domestic product growth. Think of GDP warrants as a bit like stocks. Instead of owning a piece of a company, investors own a share of the country’s economic expansion. The stronger the upturn, the higher the payout.

What seemed like a good idea then is now a looming headache for Zelenskiy, a former TV comedian who entered politics formally just a year ago. During the restructuring handled under the previous government, the result of an International Monetary Fund bailout, Kyiv convinced bondholders to write off $3.2 billion in exchange for the warrants. As the instruments pay out over the next few decades, Ukraine could end up paying out much more than it saved by restructuring.

Although the total amounts are modest compared with, say, the U.S. national debt, the impact on Ukraine could be significant. The government doesn’t have to pay any returns on the securities when real GDP growth is slower than 3% a year. It will make a small payout for growth from 3% to 4%. The big action comes when annual growth exceeds 4%. For example, in a year where the pace of expansions reaches 6%, Ukraine will be on the hook to pay as much as 40¢ on each warrant, which would cost about $1 billion.

That’s hardly a long shot: Ukraine has achieved annual growth of at least 6% five times since the beginning of the millennium, and its government is targeting medium-term growth of as much as 7%. Based on those projections, the government estimates its cumulative obligations for the warrants could exceed $10 billion by maturity in 2040. For investors, there’s a promise of big payoffs from the warrants, which trade at about $1 each. For someone buying them at that price, a year of 6% annual GDP growth would translate into a 40% return.

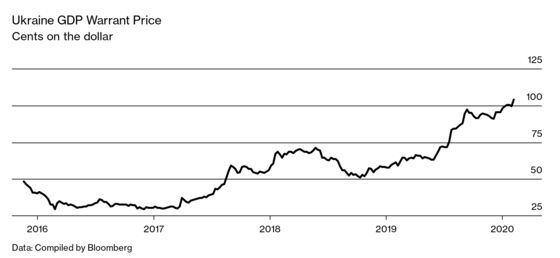

Zelenskiy’s government may have a bit of breathing room, because the restructuring agreement caps payout amounts until 2025. Next year is the first year Ukraine has to pay out on the securities, and it may need to come up with as much as $100 million for investors. Government officials have already said they’re looking at ways to minimize the liability before the first payments are made. Some investors anticipate the government will offer to buy back the warrants or exchange them for bonds.

Ukraine’s financial rebound has surprised many investors. The hryvnia lost more than half of its value in an economic crisis after Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 and Kremlin-backed rebels launched an insurgency in the country’s east. With its industry shattered, in 2015 the country’s pro-European Union leadership entered the IMF program that retired 20% of its external debt in exchange for the warrants.

Four years later, investors have piled in. Ukraine’s currency and foreign bonds handed them the highest returns among all emerging markets in 2019, according to the Bloomberg Barclays Index.

There’s a danger those gains could offer an illusion of security to Zelenskiy, whose grasp of economics has been the brunt of ridicule in his own government. The president understands exchange-rate changes only when they’re explained to him using the price of his New Year’s potato-and-mayonnaise salad, Prime Minister Oleksiy Honcharuk quipped, according to a recording later made public.

GDP warrants have been a part of other big sovereign debt restructurings, but with mixed results. Argentina offered similar notes to creditors who were burned by the country’s $95 billion default two decades ago. Plans to buy them back, saving as much as $9.4 billion, were scrapped in 2017 after the country decided to instead use proceeds to roll over maturing debt. The warrants have since fallen to about a sixth of their value at the time.

Greece, too, offered GDP warrants in its 2012 restructuring. They’ve been trading at less than half their issue price for the last five years. The Greek instruments, unlike Ukraine’s, were structured to put a lid on future payouts for blockbuster growth and show little sign of generating a payout.

“It’s not easy to say how well Ukraine and its creditors understood these instruments,” researchers Stephen Park from the University of Connecticut and Tim Samples at the University of Georgia, who have studied the warrants, wrote in an email. To be fair, they added, the recurring challenge with these deals is that they’re struck when confidence in the country is at a nadir. “It’s easy to say that Ukraine is losing really bad here,” Samples says, but that’s “because all we see is the payouts” and not whether the government gained important goodwill with creditors in 2015 by promising a share of growth down the road.

Many of the warrants’ recipients haven’t waited around. Franklin Templeton bond chief Michael Hasenstab led the group of creditors negotiating the 2015 deal. He held a significant chunk of Ukraine’s debt during the restructuring. But he wound down his holdings of the GDP warrants and exited in mid-2019.

Other members of the bondholder committee, including BTG Pactual Europe, T. Rowe Price Associates, and TCW Investment Management, have probably exited, or sold and then rebuilt, their positions, according to holdings data compiled by Bloomberg. (They all declined to comment.)

If Zelenskiy hopes to sweep the warrants off the market from the new investors that have snapped them up, it’ll cost him. The securities, after tripling in price from their initial value of about 33¢could easily trade at 130¢, the fair value estimated by Citigroup Inc. analysts.

Says David Nietlispach, a Zurich-based money manager at Pala Assets, who owns the notes: “If they want to buy the bonds back, they will have to pay a very, very high price.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeffrey Grocott at jgrocott2@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.