Even Lobsters Can’t Escape Trump’s Trade War

Even Lobsters Can’t Escape Trump’s Trade War

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In his cargo shorts and T-shirt, Mark Barlow looked anything but an international trade warrior. Yet a few weeks ago, when he slid open the door to his low-slung warehouse in a scrappy industrial lot to reveal concrete tanks filled with 375,000 gallons of 40-degree water and a fortune in live Maine lobsters, he might as well have been leading a battlefield tour.

Since the 1990s, Barlow has built his company, Island Seafood, into a $50 million-a-year business by shipping live lobsters around the world. He exported one out of every five to China until recently. A lobster plucked from a trap in Maine’s frigid waters—home to North America’s richest fishery—could surface on a dinner plate in Beijing two days later. The first months of 2018 were the best start in Island Seafood’s history, says Barlow, who this year expected to ship a million pounds of lobster to Shanghai, Guangzhou, and other Chinese cities, where he’s built relationships for a decade. Then, as Barlow, a 57-year-old bear of a man who speaks like someone who’s spent years negotiating on the docks, puts it: “The orangutan in Washington woke up from a nap and decided to put tariffs on China,” and “the Chinese stopped buying immediately.”

If you want to understand the modern global economy, the implications of climate change, and the unintended consequences of President Trump’s trade wars, then you ought to “consider the lobster.” The writer David Foster Wallace’s 2004 essay of that name riffed on the history (“Up until sometime in the 1800s … lobster was literally low-class food, eaten only by the poor and institutionalized”) and morality (“It’s not just that lobsters get boiled alive, it’s that you do it yourself”) of our love affair with Homarus americanus. To consider the lobster now, almost 15 years later, is to study crustacean economics just as U.S.-China trade tensions reach a roiling boil.

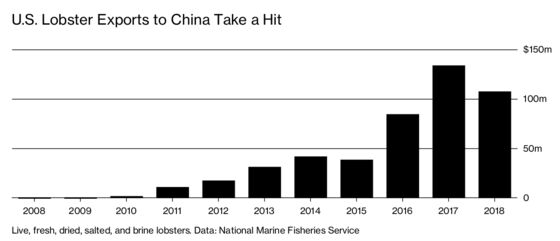

As Trump has rewritten America’s economic relationships, some of the country’s most prized exports—Kentucky bourbon, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, Midwestern soybeans—have become retaliatory targets for China and the European Union. For its part, Beijing began imposing a 25 percent tariff on a long list of imports from the U.S., including live lobsters, on July 6. “The second this happened, I said to my sales team, ‘China’s dead,’ ” Barlow says. Correspondence with his Chinese customers confirmed his hunch. “I don’t think there is [a] way to import U.S. lobster,” one buyer texted.

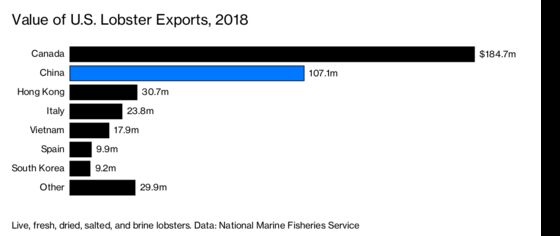

The blow is significant for Maine, the country’s top producer and exporter. The state’s lobstermen had found a lucrative market in China, where consumer demand has grown exponentially in recent years. In 2017, U.S. exports of live lobsters to China were worth $128.5 million, up from a third of that in 2015. Maine’s dealers have responded by scrambling to find other markets. Barlow has had his 26-year-old son and members of his sales team focus on other Asian markets, including Singapore and Taiwan. His biggest concern: The trade war’s consequences are unlikely to be short-term.

Luke Holden, who left investment banking in 2009 to start Luke’s Lobster, a “shack” in New York’s East Village that’s since become an international restaurant chain and lobster-processing business, is worried that the tariffs and other trade effects will force structural changes in the industry. “The reality is that these tariffs have created a very long-term uphill battle,” he says, “and we’ve just started to climb that hill.”

One problem for American lobstermen is their Canadian rivals. Thanks to a trade agreement Prime Minister Justin Trudeau struck with the EU, Canadian crustaceans now land in Europe duty-free. U.S. lobsters, meanwhile, face an 8 percent tariff with no sign of imminent relief. (While Trump is discussing a limited EU deal on industrial goods, European officials have resisted including agricultural trade, which bodes badly for lobsters.)

As a result, dealers in Maine have begun investigating whether to open bonded warehouses so they can sell Canadian lobsters to clients in Europe and China, bypassing tariffs. Others have already begun shifting operations across the border to Canada to take advantage of the tariff advantage there. “This guy [Trump] has handed Canada the lobster industry—a $1.5 billion industry,” Barlow says. “He’s just handed it to Trudeau: ‘Here you go, boys.’ ”

Across the border, Canadians have started to complain about transshipping. (If the term sounds familiar, that’s because it was at the root of the steel tariffs Trump imposed on Canada earlier this year when he claimed the country had become complicit in China’s trade cheating.) “Lobster from Maine is coming into Canada and being exported to China,” says Geoff Irvine, executive director of the Lobster Council of Canada. “Everybody knows what’s happening. … Anything that isn’t Canadian lobster should not be sold as Canadian lobster.”

There is yet another force at work—Chinese finance and the country’s seemingly insatiable appetite for natural resources. In recent years, Chinese seafood companies have taken stakes in some Canadian wholesalers and begun running weekly charter flights carrying live lobsters from Halifax, N.S., to Chinese cities. “There’s been significant Chinese investment in the [Canadian] industry for several years,” Irvine says. “They’re buying plants and buying capacity to ship.”

Irvine argues the Chinese investors act like any other. But Barlow and others in Maine see a more worrying trend at work, one that echoes the sort of rapacious acquisitions and disruptions that have come in other resource-driven industries that China has targeted elsewhere. “They’re going to wrap up the logistics [and] grab pricing power,” Barlow says. While he credits Trump for calling attention to China’s economic practices, he doesn’t like the president’s tactics and worries that he’s actually helping to accelerate Chinese control of his industry. “He’s not hurting [China],” Barlow says. “They’re laughing at him.”

The present and future of the Maine lobster looks very different to Kristan Porter, who since 1991 has been tending lobster traps off the tiny fishing village of Cutler a half-hour’s drive from the Canadian border. In March, just as the trade-war rhetoric heated up, Porter took over the presidency of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association, which represents the bulk of the state’s 5,400 independent fishermen. The issue of China’s tariffs and Trump’s trade wars, however, “is a long way down the list for most guys,” he says.

More important for the association’s members is a looming reduction in quotas on the herring catch, which is likely to drive up the cost of bait, and updated regulations to protect migrating North Atlantic right whales from getting entangled in the ropes lobstermen use to retrieve their traps.

Why the lack of concern? Shouldn’t trade problems be a higher priority? Perhaps, but the overall strength of the U.S. economy seems to provide courage for conviction—and the reality is that times have been very good of late for the Maine lobster industry. “We’ve been kind of spoiled the last few years,” Porter says.

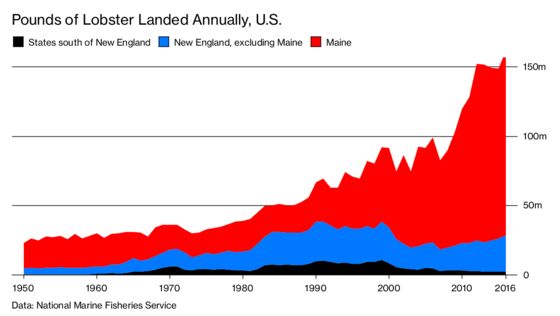

Indeed, from the end of World War II until the late 1980s, there was a remarkable consistency to Maine’s lobster catch. Year after year it ran about 20 million pounds. In 1990, Maine’s lobstermen had what was then their most lucrative year ever. The 28 million pounds they caught was worth $61.6 million in today’s dollars. In the decades since, however, upward trajectories have transformed the industry. By 2016, Maine’s lobster catch had reached 132.5 million pounds and become worth $540.3 million, both records.

Most everyone agrees the surge in the lobster catch has been the result of an increase in the population rather than overfishing. Experts attribute the population explosion to a confluence of factors including the industry’s conservation practices. Maine’s lobstermen have abided by minimum size restrictions since the 1890s and throw back egg-bearing females as well as the largest male lobsters, which are considered the “brood stock.” Two other factors are having an impact: The overfishing of Atlantic cod, a major predator of juvenile lobsters, and warming oceans that have supercharged some breeding grounds.

The latter influence, scientists say, appears to have played a major role. According to Andrew Pershing, chief scientific officer at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, the gulf has been one of the fastest-warming ocean ecosystems in the world in recent decades. In the past 15 years, the Gulf of Maine—bounded by Cape Cod in the south and the Bay of Fundy and Nova Scotia to the north—has seen its temperature rise at a rate more than seven times the global average.

The ramifications depend on your vantage point. The waters off Rhode Island and Long Island, which once had thriving lobster fisheries, have become too warm, effectively killing off the industries there. Farther north, the water temperature has hit a sweet spot at about 54F that’s turned an ideal cobble-bottomed seafloor in Maine’s northernmost waters into the lobster equivalent of an industrial-scale lobster-breeding factory. The big question is how long that will last. The Gulf of Maine is continuing to warm; again this summer the waters experienced another ocean heatwave. Aug. 8 was its second warmest day on record, at 68.93F.

The warmer currents have also brought other creatures into Maine’s waters, including seahorses normally found farther south and lobster predators such as black sea bass. They also are being blamed by some scientists for a decline in the juvenile lobsters that “settle” on the sea bottom, says Richard Wahle, the bearded and bespectacled marine biologist who heads the Lobster Institute at the University of Maine and has tracked the population of juvenile lobsters from Rhode Island to Newfoundland for years.

Lobsters take seven or eight years to grow to the 1.25-pound size that’s the workhorse of the industry, and Wahle’s American Lobster Settlement Index has been a remarkable predictor of future catches. In recent years he’s tracked a noticeable dip in the population; at one point, experts even spoke of a lost generation of juvenile lobsters.

Beyond attracting new predators, Wahle says, the rising temperatures have also had a negative impact on a key part of the lobster food chain. Studies have shown a decline in the population of copepods, the tiny one-eyed crustaceans that larval lobster rely on as a staple. One theory, Wahle says, is that the warmer temperatures have led to a collapse of the even tinier fatty phytoplankton that the copepods rely on for food.

The end result doesn’t look good for the future of the lobster in Maine or Canada. In a study published earlier this year, Arnault Le Bris, a researcher at Newfoundland’s Memorial University, working with Wahle, Pershing, and other leading researchers, predicted that warming waters would lead to a reduction in the annual Atlantic lobster harvest by at least 40 percent by 2050.

Maine’s lobstermen are sensitive to such doomsday scenarios, which have been used by the state to justify new regulations. Some skeptics argue that rather than disappearing, juvenile lobsters have simply been moving into deeper, cooler waters. The fishing, too, is increasingly moving offshore, thanks to larger and more powerful boats that allow lobstermen to go 30 to 40 miles out to sea in search of new fortunes.

A fall in the catch in 2017 from the 2016 peak prompted fears that Maine’s lobster decline had begun. But people in the industry say lobstermen this year are continuing to see plenty of smaller, younger lobsters in their pots, which bodes well for at least the near future.

The real threats for many in the industry are more immediate. Tom Philbrick, a towering former college basketball player who runs his lobster wholesale business from a ramshackle office above a dockside restaurant in the popular tourist haven of Boothbay, has watched his margins erode this year—in part because of the China tariffs. The 50¢ to 60¢ per pound profit he was getting last fall on export-quality lobsters that passed through his tanks has fallen to 30¢. Considering that he plans to buy 2 million to 3 million pounds of lobsters this year to sell on to bigger dealers such as Barlow, that’s a substantial financial hit.

Yet, like many in the industry, Philbrick is a fan of Trump and likens supporting the president’s trade war to backing a real war, with all of the sacrifices that entails: “Sometimes you’ve got to take two to three steps backwards to get forward.”

For Barlow, the trade wars are forcing him to rethink his business model. He’s been considering using a Canadian subsidiary he set up years ago to export to Europe and take advantage of Canada’s new EU trade deal. He’s also begun considering layoffs. “We’re getting absolutely slaughtered,” he says.

The irony for Barlow, of course, is that the president has positioned himself as the champion of the little guy against an intrusive government—a fact that’s only increased Barlow’s frustration with Washington and Trump. “There’s nothing that I did to perpetuate this,” he says. “There’s a million ways to skin a cat, and [the best way] is not by hurting your own citizens.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Joel Weber at jweber66@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.