Debt-Rule Showdown Will Shape Europe’s Economy for Years to Come

Debt-Rule Showdown Will Shape Europe’s Economy for Years to Come

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Europe’s policymaking class is readying itself for a clash that may reverberate for years to come.

The huge public-borrowing binge needed to fund spending during the Covid-19 crisis is forcing a rethink of the European Union’s rules governing debt and deficits, exposing a political fault line over economic theory.

Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi and French President Emmanuel Macron are pushing to free their economies from the EU’s pre-pandemic strictures. They face resistance from leaders of northern countries, which pride themselves on appearing more fiscally responsible—as well as institutional inertia. The quarter-century-old Stability and Growth Pact is contained in a treaty, so any amendments would have to be ratified by 27 legislatures.

With the European Central Bank having just completed a contentious revamping of monetary policy, the outcome of this next battle will define the scope of fiscal action for the coming decade, and perhaps the EU’s growth prospects as well.

“Many in southern Europe believe that there should never be a real return to rules,” says Mario Monti, one of Draghi’s predecessors and a former EU commissioner present for discussions when the regime was agreed to in the 1990s. “High government deficits, largely financed by the ECB, are seen as the key engine for growth,” says Monti, whose own view is that structural reforms should take precedence.

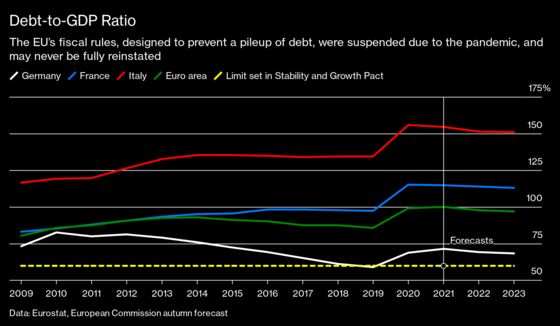

The Stability and Growth Pact was forged at the dawn of the euro at the behest of the Germans, who sought a means to enforce spending restraint on their more profligate neighbors to the south. It caps deficits at 3% of gross domestic product and debt at 60% of GDP. Violators are subjected to hectoring and fines.

The rules were devised during a time when leaders could not possibly foresee that governments would be able to borrow at today’s historically low interest rates, which is why economists now often describe the pact as an unnecessary straitjacket. In 2021 the European Commission activated an “escape clause” in the agreement, freeing countries to spend extraordinary sums to salve the human and economic pain of Covid. Nations must now agree on what will happen when the suspension ends in 2023.

The so-called frugals want only limited changes to the original rules. Their view is that the ECB’s vast purchases of government bonds as part of the pandemic rescue effort have made governments overly dependent on central bank support.

“We need consolidation of fiscal policy going forward, to relieve the ECB from this burden, and to increase the resilience of the euro area,” says Lex Hoogduin, a professor at the University of Groningen, who was an adviser to the ECB’s first president, Wim Duisenberg, and later a chief economist at the Dutch central bank.

Another camp, led by the Italians and the French, and including Spain and others, argues the pact’s arbitrary constraints act as a brake on economic growth and contribute to making debt loads unsustainable. Those with long memories will recall how, in its early years, its limits proved too strict even for Germany.

Such views reflect the economic consensus crystallized by the Greek debt crisis of the last decade, in whose wake the International Monetary Fund issued a mea culpa, saying stringent austerity measures imposed as a condition for debt relief had worsened the country’s predicament. “It is investment that will favor growth, and growth that will accelerate debt reduction,” French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said on Dec. 14, articulating the prevailing philosophy for advanced-world economies.

Lars Feld, formerly a member of Germany’s panel of economic experts and a professor of economic policy at the Albert-Ludwigs-University of Freiburg, says such ideas have gone too far. “It’s the same old line. I really cannot hear it anymore,” he says. “I don’t think the German government should buckle, and it should ask instead what is being done to reduce the debt burden.”

Germany’s new finance minister, Christian Lindner, is a fiscal hawk. But so far he’s played a diplomatic game, telling Le Maire on Dec. 13 that “we see both sides.”

Draghi, whose heroic, “whatever it takes” defense of the euro during his tenure as ECB president gives him enormous stature, has repeatedly condemned the current pact, saying its rules are “obsolete.” He and Macron sealed a bilateral treaty on Nov. 26 pledging more intense cooperation in a host of areas, including fiscal policy.

His disdain is reflected in his government’s proposed budget for 2022-24, which doesn’t envisage a return to 3% deficits. This provoked a Nov. 24 call for “caution” by the EU Commission, a view that finds favor north of the Alps. “It was right to react quickly in the pandemic,” says Gertrude Tumpel-Gugerell, an Austrian former member of the ECB’s Executive Board. “But we need to bring back spending to more normal levels.”

Among the proposals for changes is one from the economists at the European Stability Mechanism, the euro area’s crisis lender, who suggested in a paper published in October that governments consider a higher debt ceiling of 100% of GDP—the 60% limit has been long surpassed by all the major economies, including Germany’s—and a more flexible approach to deficit ceilings.

The European Fiscal Board, a panel of EU advisers, advocates allowing for a slower pace of debt reduction while recognizing the continuing need for “clear and recognizable numerical goal posts” such as the controversial 3% budget deficit rule. Another EFB idea under discussion is a clause that would provide leeway for green investment, echoing the sort of policy Germany is pursuing.

Discussions will be long and contentious. France, which is about to assume the rotating presidency of the EU, plans a summit in March, though the commission is also preparing to buy time by proposing interim fiscal targets for 2023.

The criteria “were hard to apply before—imagine now, with the new high debt levels?” Paolo Gentiloni, the EU commissioner for the economy and financial affairs, said at a conference on Nov. 28. “We will discuss it a lot in the coming months, but in the meantime, ignoring the issue would be a grave mistake.” —With Kati Pohjanpalo and William Horobin

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.