Europe Sleepwalked Into an Energy Crisis That Could Last Years

Europe Sleepwalked Into an Energy Crisis That Could Last Years

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The retired salt caverns, aquifers, and fuel depots that hold Europe’s stockpiles of natural gas have never been so empty at this point in winter.

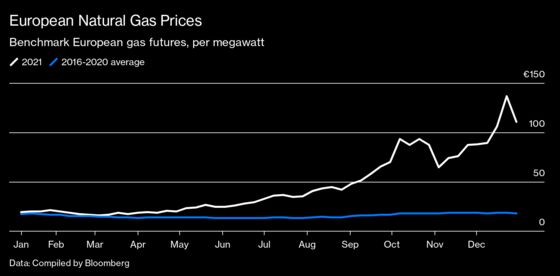

Just four months after Amos Hochstein, the U.S. envoy for energy security, said Europe wasn’t doing enough to prepare for the dark and cold season ahead, the continent is grappling with a supply crunch that’s caused benchmark gas prices to more than quadruple from last year’s levels, squeezing businesses and households. The crisis has left the European Union at the mercy of the weather and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s wiles, both notoriously difficult to predict.

“The energy crisis hit the bloc when security of supply was not on the menu of EU policymakers,” says Maximo Miccinilli, head of energy and climate at consultants FleishmanHillard EU. He expects the energy crunch to keep prices volatile and also trigger more political tension between regulators in Brussels and the leaders of the bloc’s 27 member states.

Although the situation came to a head abruptly, it’s been years in the making. Europe is in the midst of an energy transition, shutting down coal-fired electricity plants and increasing its reliance on renewables. Wind and solar are cleaner but sometimes fickle, as illustrated by the sudden drop in turbine-generated power the continent recorded last year.

Moscow’s increased leverage over its neighbors became apparent at the tail end of the last winter, an unusually cold and long one that depleted Europe’s inventories of gas just as its economies were emerging from the pandemic-induced recession. Over the summer, state-controlled Gazprom PJSC began capping flows to the continent, aggravating shortages caused by deferred maintenance at oil and gas fields in the North Sea and raising the stakes on a costly and long-delayed pipeline project championed by the Kremlin.

At the same time, countries from Japan to China were boosting their imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in preparation for the coming winter. All of this left Europe struggling to replenish its dwindling stockpiles during the warm months, when gas is less expensive.

Still, Europe’s leaders betrayed no alarm. On July 14, the European Commission unveiled the world’s most ambitious package to eliminate fossil fuels in a bid to avert the worst consequences of climate change. With their eyes trained on longer-term goals, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions at least 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels, the politicians did not sufficiently appreciate some of the potential pitfalls that lay immediately ahead on the road to decarbonization.

Europe’s natural gas production has been in decline for years, which has left it more reliant on imports. Now, Russia stands poised to further cement its position as the bloc’s top supplier. Gazprom and its European partners have plowed $11 billion into Nord Stream 2, a 1,230-kilometer (764-mile) pipeline running beneath the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany.

Repeatedly delayed by U.S. sanctions, the decade-long project hit another roadblock this fall, when a new coalition government took power in Germany and the country’s energy regulator put final approval on hold. The move further roiled European energy markets, where gas prices had been breaking records day after day since July. Putin, in a televised speech delivered on Dec. 24, touted the benefits of the controversial conduit, saying “the additional volumes of gas on the European market would undoubtedly lower the price on the spot.”

A recent bump in LNG imports from the U.S. has provided some relief, but it’s temporary at best. France needs to take several of its reactors offline for maintenance and repairs, resulting in a 30% reduction in nuclear capacity in early January, while Germany is moving ahead with plans to shut down all of its nuclear plants. With the two coldest months of winter still ahead, the fear is that Europe may run out of gas.

Storage sites are only 56% full, more than 15 percentage points below the 10-year average. “In none of the past years since records began have we had comparably low storage levels at this time,” says Sebastian Bleschke, head of INES, the association of German gas and hydrogen storage system operators. Barring an increase in Russian exports, something that doesn’t appear to be in the cards, levels will be at less than 15% by the end of March, the lowest on record, according to researcher Wood Mackenzie Ltd. And that’s assuming normal weather conditions.

With energy policy largely in the hands of member states, EU officials lack the authority to compel national governments to replenish gas inventories more quickly. To make matters worse, Russia is building troops on the border with Ukraine, a move U.S. intelligence sources say presages a possible invasion. About a third of Russian gas flowing to Europe crosses Ukraine, and though shipments weren’t disrupted during Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, there’s no guarantee that would remain the case if a war were to break out this year.

The energy situation limits the scope of actions Western powers can take to counter Russian aggression, says Jason Bordoff, director of the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University. “The ability of Europe and the U.S. to respond to a Russian invasion is constrained both by a desire not to exacerbate Europe’s energy crisis by sanctioning Russian energy exports and, more broadly, by the threat that Russia could retaliate to any confrontation by restricting gas flows into Europe, as Russia did in 2006 and 2009,” says Bordoff, a former energy and climate adviser in the Obama administration.

Traders are already preparing for the worst, with prices for gas delivered from spring through 2023 surging about 40% over the past month. Some say the crunch could last until 2025, when the next wave of LNG projects in the U.S. starts supplying the world market.

“It’s hard to see how decent levels of gas storage can be achieved without additional Russian exports via Nord Stream 2 or existing routes,” says Massimo Di-Odoardo, vice president for gas and LNG research at Wood Mackenzie. “2022 will be another volatile year for European gas prices.” —With Elena Mazneva, Olga Tanas, and Vanessa Dezem

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.