The EU Carbon Market Perks Up After Years in the Doldrums

The EU Carbon Market Perks Up After Years in the Doldrums

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Sixteen years ago, Europe introduced a market based on what was then a revolutionary notion: forcing companies to cut greenhouse gas emissions by issuing credits that allow them to pollute up to a certain level. If they spew out more, they have to buy allowances from other companies. If they pollute less, they can sell their extra permits and bank the cash.

This so-called cap-and-trade program, modeled after a U.S. effort to control acid rain, set carbon dioxide limits for more than 11,000 facilities in sectors such as power, paper, and cement (and later, aviation). It was a great idea that helped the European Union overcome a decade-long stalemate on a carbon tax, but it had a fundamental flaw: The permit levels were determined in prosperous times, and there was no plan for reducing supply in the event of a sharp fall in output.

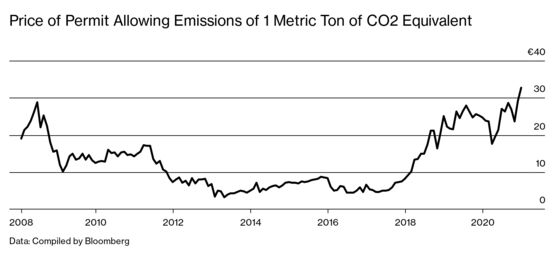

When the global economy went into a funk in 2008, emissions plummeted, sending prices for permits into a tailspin. The problems were aggravated by imports of cheaper credits from outside the region issued under a carbon-reduction program overseen by the United Nations. By 2013 the cost of emitting a ton of carbon had tumbled from a pre-crisis high of €31 ($38) to just €2.50.

Now, after three reforms that reduced the number of available permits, Europe’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) is back on track—even though production is lower because of the coronavirus pandemic. On Jan. 12 the cost of emitting a ton of CO₂ hit €35.42—a record—and consulting firm Energy Aspects predicts prices will reach €40 this year. “ETS has shown it’s a resilient system, and it’s now getting stronger,” says EU climate chief Frans Timmermans. “This is one of the best instruments we have to influence the behavior of industry and the necessary reduction in the use of carbon.”

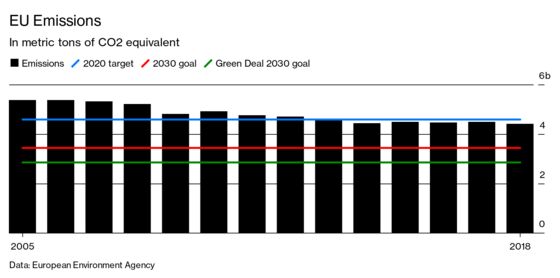

The resuscitation of the ETS has come in response to the limits on permits and expectations that the supply will soon shrink even faster. From 2013 to 2020 the volume of permits issued was reduced 1.74% annually, and from this year it will drop 2.2%. In December, EU leaders endorsed a revised 2030 target of cutting pollution by at least 55% from 1990 levels, vs. an earlier goal of 40%, as part of the EU’s so-called Green Deal, a sweeping environmental program aimed at making the region carbon neutral by 2050.

This summer the European Commission, the bloc’s regulatory arm, is due to suggest measures designed to align the cap-and-trade program to the tighter emissions target. Proposals include a speedier reduction in the volume of permits issued, a one-off reduction in the cap to better sync it with the 55% goal, and an expansion of the program to include the construction industry and maritime and road transportation. Given the dealmaking that will be required in the 27-nation EU, approval of any overhaul will take at least a year.

The most aggressive measures under consideration could push the cost of emissions to €80 per ton by 2024, according to BloombergNEF, Bloomberg LP’s energy transition research service. But that scenario is unlikely, because European governments would resist putting their companies at a competitive disadvantage to rivals from places without carbon limits. Jahn Olsen, head of EU carbon at BNEF, predicts prices will remain below €50 per ton until the middle of the decade as the commission seeks to tighten emissions targets while discouraging companies from relocating production to places with laxer climate rules. “One thing is certain: Carbon prices are going from being merely a regulatory issue to a strategic risk for companies,” Olsen says.

The EU carbon market has already driven significant emissions reductions in the power sector, where CO₂ pollution fell 15% in 2019 as electricity from renewables displaced fossil fuels. A bigger challenge is heavy industry, which registered a 2019 drop of just 2% in carbon emissions. Accelerating the shift would require a massive uptake of cheap, clean energy, with many member states backing new and unproven technologies such as fueling factories with hydrogen. With the pool of permits shrinking, companies will need to choose between investing in cleaner production—the real goal of the program—or buying more allowances, which will keep putting upward pressure on prices, says Ingo Ramming, a carbon expert at Commerzbank AG. “The increase in European carbon prices and public debate on climate change have moved sustainability from niche to mainstream,” he says. “It has become part of corporate strategy.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.