A College Football Town Tries to Survive a Ghost Season

A College Football Town Tries to Survive a Ghost Season

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On a typical fall Saturday at the University of Oregon, Greg Wells would be patrolling a cacophonous corridor of 24 tents in the parking lots next to Autzen Stadium. An Oregon alum and chief executive officer of Tailgate Pal, Wells and a staff of up to 10 would be coordinating the pregame experience for hundreds of fans on hand in Eugene to see their Ducks play. They would take care of everything down to the coolers chilling local IPAs and the hot dogs and ribs from a nearby catering company. For an added fee, tailgaters could rent flatscreen TVs, snack on cupcakes topped with green Os, or play cornhole.

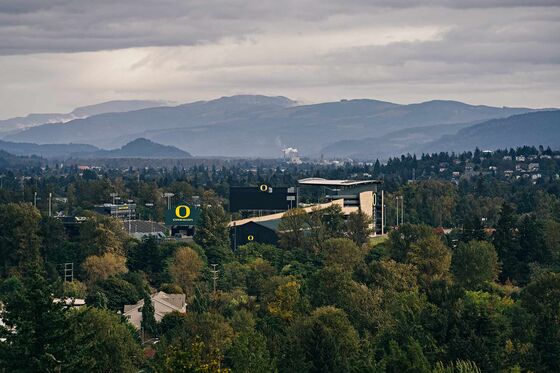

Normally, in this city of 172,000 people where I grew up, Autzen Stadium fills up for Duck games with more than 50,000 fans seven times a season; countless more people crowd into bars or restaurants, or attend parties in Eugene. Around campus, it’s hard to find a coffee shop, hair salon, or front yard that doesn’t have green or yellow paraphernalia on display. “Go, Ducks” is an accepted salutation.

On Saturdays this fall, though, Tailgate Alley is quiet enough that you hear cars go by on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, which frames the stadium to the north and east. Wells has furloughed his staff and isn’t taking future reservations; he’s unsure if his business can hold on as he relies on cash from other ventures to cover Tailgate Pal’s insurance payments, warehouse rental fees, and phone bills. “I felt blindsided like everybody else,” Wells said in August. “It’s just unthinkable, right? It’s like someone canceled Christmas. I mean, no college football?”

There was a lot to look forward to this season: the continued success of a team that was 12-2 a year ago and won the Rose Bowl (with Justin Herbert, now quarterback for the Los Angeles Chargers), good rivalry games at home, and the unveiling of one of the largest video scoreboards in the country. Instead, on what would’ve been opening day in early September, some sports bars were open but at a fraction of capacity. Many campus apartments and new hotels were vacant, their parking lots mostly empty grids of gray. Homeless communities, long part of life in Eugene, had proliferated at parks and street corners. The additional city buses that typically shuttle fans to and from the stadium were nowhere to be seen, with many of their drivers furloughed in anticipation of $12 million in expected lost revenue from the annual transit budget. At the airport, passengers were arriving and going at 46% of their 2019 levels. “We typically have people coming in and out for home and away games,” said Andrew Martz, acting assistant airport director and an alum. “Everything is so strange now.”

The Pac-12 conference announced late last month that its teams would play a seven-game, conference-only season starting in early November—without fans in or immediately around the stadium. In Eugene the ghost season is laying bare how interwoven football is with the local economy. Anticipated revenue from home games has been such a given that neither the city nor the school has bothered to analyze recent numbers. According to the most current estimate, from 2015, the average home game brings in $5.8 million for the community, with 60% of attendees coming in from out of town, says Kari Westlund, president and CEO of Travel Lane County, a local nonprofit. That assessment is “likely low,” she says, given the team’s success in the past five years.

Football “is critical for us,” says Greg Evans, a season ticket holder for 24 years who represents the 6th Ward on Eugene’s city council. “We’re not San Francisco.” Stanford and the University of California at Berkeley, fellow members of the Pac-12, are “going to be OK,” he adds, likening Eugene to a factory town whose main employer has shut down. “They don’t depend on football for their economy.”

A version of this story is unfolding in sports-crazed college towns, from Eugene to Lincoln, Neb., and Tuscaloosa, Ala., where teams are playing with no fans or with strict caps on attendance. Nationally, there’s little consensus on how to handle the novel coronavirus. The 23 campuses in the California State University system are mostly virtual. Other schools, such as Oregon, are taking hybrid approaches, weaving in testing and social-distancing protocols, with some students on campus and others attending virtually.

In the Southeastern Conference, teams such as Auburn and Alabama are playing at 20% capacity. In the Big Ten, which started its season on Oct. 23, a limited number of family members of players and coaches are allowed inside stadiums. Others, such as the Ivy League and the largest conferences of historically Black colleges and universities, have canceled or postponed their seasons.

When Daryle Taylor started working as a dishwasher at the Original Pancake House in 1969, Eugene was a sleepy timber town. The restaurant just north of campus served lumberjacks, workers from the nearby Williams Bakery, and a handful of students and instructors. This continued even into the 1990s, when methamphetamine labs started blowing up and the streets were sometimes aflame in political protest. Tonya Harding was the state’s most famous athlete. Taylor says most of his siblings worked at the mills; he stayed on at the Pancake House, eventually becoming the owner. “At least here, I got to eat,” he says.

It wasn’t the best environment for recruiting. Kenny Wheaton, a Ducks safety and cornerback from 1994 to 1996, spent most of his redshirt freshman season sitting in Autzen’s empty stands, wondering why he’d left his hometown of Phoenix. He recalls walking to the stadium for practice, and “you’d have people flipping you off, telling you to get out of the way,” he says. “The team wasn’t winning.”

Under head coach Rich Brooks, the Ducks generally finished in the middle of the conference standings. There were so few fans at Autzen that my parents often took my older brother and me there so we could run around the empty stands. Tickets were often handed out free, or close to it.

But then, late in a close game in October 1994 against the University of Washington, Wheaton intercepted a pass and returned it 97 yards for a touchdown, sealing the Ducks’ first victory against the Huskies in six years. The win also sent the Ducks to the conference championship. Video of Wheaton’s feat, known in local lore as “the Pick,” still plays at the stadium before every home game; it’s considered the turning point in the program’s fortunes. Today, Wheaton is on billboards as the face of Pick Insurance and immortalized on the walls of the Pancake House, which has become a museum to Eugene sports history.

Around the same time, one of the school’s most famous alums, Phil Knight, CEO and co-founder of Nike Inc., started funneling millions of dollars to the campus, recognizing the marketing and growth potential of college sports for brands such as his. The Ducks started wearing flashy, specially designed Nike uniforms, working out in an NFL-caliber practice facility, and taking chartered flights to away games.

Some of Knight’s money also went to build a new library and law school, as well as the “jock box,” a $41.7 million study center for student athletes. Eventually, Matthew Knight Arena, where the Ducks basketball teams play, went up in place of the old Williams Bakery. Named for Knight’s elder son, who died in a scuba diving accident in 2004, the facility features a distinctive tree-patterned court. Hayward Field, where Nike’s history as a running shoe company began, just got an estimated $200 million Knight-funded renovation. (It sat empty this summer with the postponement of the U.S. Olympic track & field trials that were to be held there, a hit of at least $37 million to the local economy, according to city officials.) The influx of money gave the university a national profile. Aspiring NFL players and Olympians were drawn to the city, transforming it into a quirky sports hamlet.

When Taylor rose from dishwasher to become the owner 10 years ago, he enlisted his twin brother Duran, his children Chris and Julie, and his son-in-law Scott to work with him. He needed the help: The Pancake House had become a regular stop for Oregon athletes and their families and fans. In the days before a home game, Julie would call local hotels to see how full they were. This would determine how much flour, eggs, and butter to buy, and how many workers to schedule.

In March, when Oregon’s Democratic Governor Kate Brown mandated that all restaurants shutter their dine-in service, Julie says her father and her husband stocked up on to-go containers at the local Costco. She transformed the cozy space into a takeout business and gradually brought back most of the 11 waitstaff she’d furloughed to handle takeout orders. The restaurant took out a Paycheck Protection Program loan, and the dining room was repainted and redecorated while it was closed. (It reopened for indoor dining at about 70% of capacity in May.) “I thought this would be the time to do it,” Taylor says.

Taylor owns the building, so the restaurant doesn’t have to worry about paying rent. Still, before the pandemic, to-go orders were 5% to 10% of revenue, Julie says. She declines to detail what percentage of total business they make up now, but she describes it as a “mandatory” part of operations. In August, she says, the restaurant was doing 70% of the business it was doing a year ago; in September, with no football, it was doing more like 65% to 70%. She says she doesn’t know what to expect now that only three home games will be played—without fans. “Those numbers are really down,” Julie says.

Many Oregon restaurateurs were on the precipice heading into fall. In a recent state survey published by the National Restaurant Association, 40% of them said that if current conditions continue, “it is unlikely their restaurant will still be in business six months from now.” Many spots that are part of the Ducks ecosystem might not survive. Turtles, a game-day mainstay known for its burgers, closed after 21 years. Barn Light, an exposed-brick watering hole serving Frito pies and custom cocktails, is said to be for sale. The Webfoot Bar and Grill, a Jell-O shot-type place, has been closed through the start of fall.

Dallas Johnson, general manager of Sidebar, a 25-screen sports bar, was working the beer taps on Aug. 11 when the earliest reports about the Pac-12’s plans came out. Initially, word was that the season would be postponed until spring. Sidebar had managed to reopen only in mid-May, at a third of its 165-person capacity, drawing on a PPP loan to stay afloat. Johnson says he threw his hands up in the air when he heard there wouldn’t be football in the fall. “I thought: ‘Time for another beer.’” The shortened season came as a welcome reprieve. “We’re excited,” he says. Sidebar will be open on game day, by reservation only.

It’s not clear how much help largely fanless football is going to offer, though. Eugene’s service and hospitality industry needs customers such as Michael Hoag. For months this spring and summer, Hoag, an Oregon alum who lives in Los Angeles, looked forward to booking trips with his girlfriend to see games. (She went to conference rival University of Southern California, but they make it work.) From his first Ducks home game as a freshman in 2004, Hoag says, “I immediately got swept in.” He witnessed the team’s 2012 Rose Bowl win over Wisconsin and has followed the pro career of Oregon quarterback and Heisman Trophy winner Marcus Mariota closely. Fall Saturdays are measured in thirds: before, during, and after games. “That atmosphere, sense of community, how fun that stadium was—I had never experienced college football like that,” Hoag says. “I don’t know how someone doesn’t fall in love with that collective joy.”

As fall rolled around, it became clear to Hoag and tens of thousands of others that there would be no trips to Eugene. The Inn at the 5th, an upscale boutique hotel favored by out-of-towners, now houses essential university, hospital, and delivery workers in some of its 69 rooms. “That allowed us to stay open,” says Kathryn Allen, the general manager. Marriott, Hilton, and InterContinental all built outposts near Autzen Stadium in recent years. Representatives from the hotels didn’t return requests for comment about their Eugene properties, but I drove by the buildings for months this summer and fall, and they seemed pretty barren.

The collateral damage from this season extends to other kinds of enterprises, too. The Autzen-adjacent Eugene Science Center is cutting a quarter of its annual budget, due to tens of thousands of dollars in lost funds from parking cars, says executive director Tim Scott. It’s already had to furlough or lay off two-thirds of its employees and kept its doors closed to the public for the summer. “This is by far the biggest fundraiser of the year,” Scott says. “It’s going to be a critical situation.” Boy Scout Troop 100 is facing a budget crisis for similar reasons, says Tony Reyneke, who manages the troop’s parking program. A typical season has scouts, scout leaders, and their parents parking 1,200 cars, charging anywhere from $20 a car to $1,200 for an RV season pass. At a minimum, they’ll lose out on $24,000.

During the financial crisis a decade ago, the University of Oregon helped prop up Eugene’s economy. It provided jobs and retail customers, sustaining consumer spending and the real estate market. “We were really lucky,” says Anne Fifield, who has been Eugene’s economic strategies manager since 2015. But relying on income from the school has made the current situation unpredictable and hard to prepare for. Some students are on campus, and some are in Eugene taking classes remotely, but distancing protocols have tempered their usual social lives. “They have a lot of spending power, especially with bars and restaurants that have been so hard-hit,” says Fifield.

The ghost season has local officials talking about where to look for economic growth. One possibility, Fifield says, is that Eugene becomes a “Zoom town”—a cheaper place to live for workers newly untethered from office buildings and seeking an alternative to the pricier markets of Portland, San Francisco, and Seattle. It’s an idea with statewide appeal. A September report from the governor’s office discussed the potential economic benefits of telecommuting while projecting that Oregon’s labor market won’t return to health until mid-2023.

Among Eugene’s pressing concerns are how Covid-19’s toll on job losses will affect its homelessness problem. Before the pandemic, the city had the highest per-capita homeless rate in the U.S., at more than 430 people per 100,000, according to a Security.org analysis of federal data. In 2019 alone, according to city council minutes, Eugene saw a 32% increase in the number of people who experienced homelessness, a rise that local leaders attribute in part to a lack of affordable housing options. Social distancing has cut in half the number of available shelter beds. With more layoffs and colder temperatures, Emily Semple, the council representative for downtown Eugene, worries that the situation will worsen. “What are we going to do?” she asks. The irony is that a record number of people are living on the street amid a glut of empty hotels and student housing.

There are worries about the university’s financial health, too. In the fiscal year ending June 30, 2019, the University of Oregon got about $20 million—15.8% of operating revenue—from football media rights, according to the breakdown of revenue and expenses it discloses to the NCAA. About $20 million, or 15.6%, of the athletic department’s operating revenue came from football ticket sales, and about $15.8 million, or 12.4%, came from donor contributions to the football program, which many expect to decline this season. In the spring, the athletic department announced a 10% pay cut for all employees and a suspension of performance-based bonuses. Oregon’s athletic director, Rob Mullens, said in an August Zoom call with media, “We’re exploring all options.”

“You have all of these sources of revenue going down while you still have a lot of expenses,” says Willis Jones, a professor at the University of Kentucky who studies sports and higher education. “You’re going to start to really see schools feeling a lot of pressure financially around collegiate athletics.” Of course, it’s hard to feel much sympathy given the potential risk to players: The schemes put in place to boost the economies of university towns rely on unpaid labor. “The NCAA continues to closely monitor Covid-19 and is taking proactive measures to mitigate the impact of the virus,” according to the association’s website. “We’re going to do the best and right thing by our student athletes,” Mario Cristobal, the head football coach, said in August. On Oct. 24, Oregon canceled a scrimmage because of five positive Covid-19 tests within the program. (They turned out to be false positives.)

The businesses that depend on athletics will continue to feel the pressure. Wells of Tailgate Pal says he considered renting out his services to local watch parties. But with social distancing guidelines capping crowds, the economics don’t work: He can accommodate fewer fans, and those he can cater to will cost more, given the demand for personal protective equipment and sanitizer. And who’s to say the games will even be played? As of mid-October, dozens had been postponed or canceled for virus-related reasons.

Instead, Wells is looking to rent out his tents to the university, the football team, or the community for outdoor Covid-19 testing or to restaurants looking to protect guests from drizzle. “Tents are a popular commodity now,” he says. Meanwhile, for the first time in almost two decades, he’ll be watching Oregon football at his house. “I can’t even really tell you the last Saturday that I watched a game at home on my couch,” he says. “It’s so bizarre.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.