Oil Price Crash Could Hurt Trump in Texas, Help in Pennsylvania

Oil Price Crash Could Hurt Trump in Texas, Help in Pennsylvania

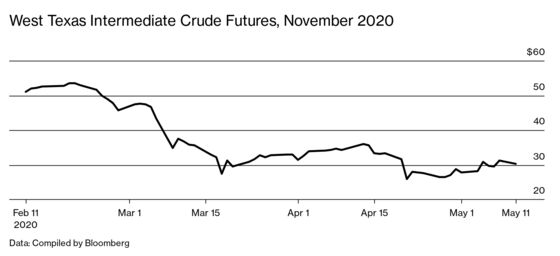

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Gasoline prices of less than $2 a gallon ought to be good news for a U.S. president with an eye on reelection: It’s a truism that American voters are hypersensitive to the price of gas and factor it into their decisions in the voting booth. But with the U.S. now the world’s top energy producer, rock-bottom oil prices are inflicting major economic damage and pose a problem for Donald Trump.

Falling prices caused by shutdowns related to Covid-19—and Saudi Arabia and Russia flooding the market in a price war—have led drillers to close down half of all U.S. oil rigs. The U.S. oil and gas industry lost 51,000 drilling and refining positions in March alone, according to BW Research Partnership, a consulting firm.

The industry’s woes will exacerbate the nation’s wider economic misery and stands to influence the outcome of the presidential race. In the runup to November, the twin shocks of Covid-19 and the oil price collapse are jeopardizing Trump’s standing in Republican Texas, the second-biggest prize on the electoral map. Yet the same energy dynamics dragging down the economy in Texas could give Trump a boost in Pennsylvania—a critical swing state he barely won in 2016—because decreased oil production potentially means higher prices and more jobs for the state’s fracking-fueled natural gas industry.

Texas, the epicenter of America’s oil and gas industry, has borne the brunt of the price crash. Because of the coronavirus crisis and the oil bust, the state “is suffering a double black-swan event,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody’s Analytics, using a term that describes rare occurrences with extreme detrimental impact.

In February, Texas ranked 30th in the country with its unemployment rate of 3.5%; by March, it was up to 15th at a rate of 4.7%. April numbers will likely send it higher.

Last month was among the most brutal in years for oilfield job cuts. Frack workers have been losing jobs the fastest in the Permian Basin of West Texas, the world’s largest shale oil field. But the pain has reached office workers, too. Halliburton Co. said on May 6 it was laying off roughly 1,000 employees from its Houston headquarters.

In a recent survey of energy workers (mostly in office jobs) conducted by the University of Houston, fewer than half were optimistic about the industry’s long-term outlook. An additional 38% said they weren’t optimistic at all. That surprised Christiane Spitzmueller, a professor of industrial organizational psychology at the university who’s been studying the oil workforce for years. “That’s pretty shattering if they don’t see a very optimistic future,” she says. “Generally, the people who’ve been in this industry are big fans of the industry and pretty firmly believe in the contributions the industry makes for society as a whole.”

Republicans have won every presidential race in Texas since 1980. But changing demographics and the economic downturn have introduced hints of purple, and Democrats are in their best position there in four decades. Democrat Beto O’Rourke came within three points of defeating Republican Senator Ted Cruz in 2018, while Democrats picked up two House seats in the Dallas and Houston suburbs. A recent statewide Dallas Morning News poll has Democrat Joe Biden in a tie at 47% with Trump in the November election.

“I think this makes it more likely that Texas goes blue sooner rather than later,” says Brendan Steinhauser, a Republican political consultant and former Tea Party activist in Austin. “The bottom line for independent-minded voters—people in the middle—a lot of those voters might say, ‘What’s my reason to support the president?’ If the argument was the economy is doing so great, well, now it’s not.”

But Texas is tricky this cycle for Biden, too. He has to woo those who supported democratic socialist Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and his Green New Deal without alienating centrists by adopting progressive energy policies that could eliminate fossil fuels and threaten oil company executives.

Chrysta Castañeda says a balanced energy platform could help Biden win Texas and the presidency. She’s a Dallas oil and gas attorney running as a moderate Democrat for the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates the oil and gas industry. “Joe Biden’s best message is, ‘Texans, I hear you,’ ” she says. “We need to take care of people who are being laid off today even as we’re actively preparing for an energy future that’s going to look much different.”

Trump has faced skepticism from an industry accustomed to Republican presidents including the Bushes, who were Texas oilmen before entering politics. “He’s generally perceived as a pro-fossil-fuel president, but his rhetoric has been the opposite. He keeps trying to jawbone down the price of oil,” says George Seay, a Dallas Republican fundraiser and founder of Annandale Capital.

“I think he’s looking at the overwhelming majority of Americans who are going to the gas pumps and want to see lower prices,” Seay says. “I also think he’s an East Coast, New York kind of person, and they remember how New York almost went bankrupt in the ’70s because of a bad economy caused in part by higher gas prices.” As recently as March 9, Trump tweeted, “Good for the consumer, gasoline prices coming down!”

The oil and gas industry is big, complex, and far-reaching. Exploration and production (that is, finding fuel and then pumping it out of the ground) is just one part of it. Dedicated so-called midstream companies build enormous pipelines that crisscross the country to move fuel around, supplemented by trains and trucks. Refineries and chemical plants turn the hydrocarbons into consumer products such as gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and feedstocks for plastic, all of which have to be moved around the country to end users. The industry has a steady hunger for steel, valves, pumps, pipes, and all manner of heavy machinery, from diesel-powered frack fleets to drilling rigs.

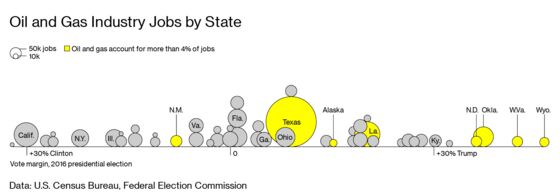

Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma have the most oil and gas jobs. But California, New Mexico, Colorado, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Alaska, and other states have significant employment in the industry as well. And Texas’ loss could end up being Pennsylvania’s gain.

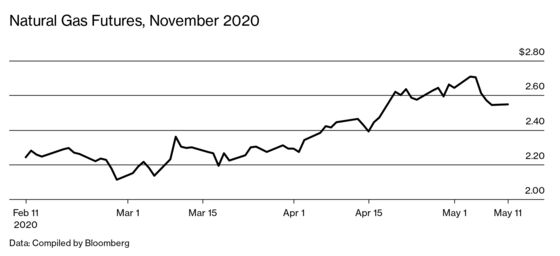

Natural gas prices have also plunged because of the pandemic. But without all the ancillary gas coming off of oil wells, those prices are emerging from their slump—which benefits the Pennsylvania-dominated Marcellus Shale region, where fracking produces natural gas without the oil. Rising natural gas prices are a thin silver lining for the Keystone State, among the hardest hit by the coronavirus.

“It provides an uptick for Appalachia. There’s no doubt about that,” says David Spigelmyer, president of the Marcellus Shale Coalition, a western Pennsylvania industry group. “Natural gas is going to be a catalyst for getting back to work, and if politicians dismiss it, they’re just hurting themselves.”

Trump eked out a victory in Pennsylvania over Hillary Clinton in 2016 with a margin of 0.72%. Polls conducted in the state in April gave Biden a lead of several percentage points over Trump. Some of those who’ll benefit from the natural gas price rise here are union workers building the equipment, gas rigs, pipelines, and power plants that extract, distribute, and use that gas. They’re torn between Trump’s energy policies and Biden’s labor policies.

“We’re in an unusual position. We have a party in the Democrats that supports us as a labor union 100% but has a wing of the party that is vehemently against the work that we do,” says Jim Kunz, the business manager of the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 66 in Pittsburgh. “And then there’s the Republicans who are very much in favor of our industry but has a wing of the party on the far right that hates us because we’re union.”

Kunz has called Trump a “snake oil salesman” but estimates that as many as 60% of his members voted for the president in 2016. He says Biden, whose hometown is Scranton, Pa., doesn’t have the kind of baggage that Clinton carried in 2016. “You can’t go talking about deplorables and a war on coal and expect people in western Pennsylvania to vote for you,” says Kunz. Trump has stoked those cultural resentments, with Pennsylvania hosting many of his once-frequent campaign rallies.

“How about going to Texas and say, ‘No Bible, no oil?’ ” Trump told a Hershey, Pa., audience in December. “But you know somebody that believes in that is Sleepy Joe Biden. He was caught telling a far-left radical activist that he would shut down fossil fuel production in Pennsylvania, you saw that.” (Biden told an activist in New Hampshire last year, “We’re going to end fossil fuel.”)

In a round of local news interviews that aired in Pittsburgh last month, Biden denied Trump’s claim. “No, I would not shut down this industry,” he said. “I know our Republican friends are trying to say I said that. I said I would not do any new leases on federal lands,” he said. “But I would not shut it down, no.”

One option that’s available to the president to shore up the entire industry between now and November: a bailout. The Trump administration has been considering possible ways of keeping capital flowing to battered U.S. oil producers. “The fact that they’re talking about direct support of the industry is a function of how important it is today vs. what it maybe was during the financial crisis even,” says Chris Duncan, an analyst at San Diego-based Brandes Investment Partners, which manages $16.6 billion, some of that in oil and gas.

Yet the idea of the U.S. government swooping in to help indebted oil producers is unpopular with voters—and even the industry is divided over relief. American Petroleum Institute President Mike Sommers has argued against special aid he says could pin a target on the industry. “We don’t want an oil-and-gas-specific program set up by government or Congress,” he says. —With Jennifer Dlouhy, Kevin Crowley, David Wethe, Ari Natter, and Steve Matthews

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.