Electing a Record Number of Women to Congress Is Great. But It’s Not the Goal

Electing a Record Number of Women to Congress Is Great. But It’s Not the Goal

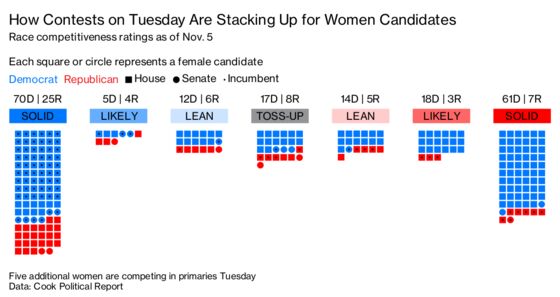

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- If every woman in a competitive race going into this year’s midterm elections wins, come January there will be 116 women responsible for crafting our nation’s laws, compared with 107 in the current Congress—a record. For representative democracy, that’s progress. “It’s rectifying an imbalance,” says Margaret O’Mara, a professor at the University of Washington who studies U.S. electoral history. “Simply, our elected representatives should reflect America.”

The addition of women to Congress has been more of a trickle than a wave. They made up less than 10 percent of Congress until 1992, the year after an all-white, all-male group of senators questioned law professor Anita Hill, a black woman, about her experience of workplace sexual harassment. The spectacle galvanized voters, particularly women, who saw their ranks in Congress double.

The newcomers elected in 1992 included Marjorie Margolies, a first-time candidate for electoral office from Pennsylvania, who won her House district by just 1,373 votes. That year turned out to be an outlier. Margolies lost her reelection by a margin of 4 percent. “We thought it was the beginning of the 50-50 representation—hah,” she says. In each election after 1992’s “year of the woman,” voters sent an average of about two additional women to Congress. The original “pink wave” still leaves men with more than three-quarters of the seats in Washington.

Gender equity aside, much of the excitement about this year’s female candidates is partisan. Of the 260 women running, 200 are Democrats. (Republicans are also running a record 60 women, but their ranks in Congress will likely shrink after the election, based on predictions from the Cook Political Report.) If party power comes with a majority, individual power comes with tenure. People who stick around build relationships, sponsor legislation, and work their way up the ranks to chair agenda-setting committees. “Where it’s going to make a difference is when women get reelected and reelected,” says O’Mara. “For material policy change, you need to be around for a while.” Parties have short windows to set their agenda when they’re in the majority—and therefore need experienced legislators who can take decisive action when the time comes.

Take New York’s Nita Lowey. First elected in 1988, Lowey will chair the House Appropriations Committee if Democrats take back the chamber. From that position she’ll have control over the government’s budget, which will become especially important if, as predicted, the Republicans retain control of the Senate, allowing them to stymie other Democratic priorities. Lowey already has big plans to fund her preferred policies. “We will work to protect women’s health care,” Lowey says, “and for expanding access for family planning both at home and abroad.”

If Republicans keep the House, Texas’s Kay Granger will likely become chair, succeeding Rodney Frelinghuysen, who is himself part of a wave—of those who chose to retire from Congress rather than face an energized progressive movement at home.

Early signs suggest this year’s wave of female candidates may have more staying power than the last. In 2016, Emily’s List, a political action committee supporting pro-choice women, consulted with about 920 women over the entire election cycle; in the past two years, 42,000 women have reached out wanting to run. “It isn’t just about this cycle,” says Stephanie Schriok, president of Emily’s List. “It’s so much bigger.” The PAC is already working with women planning to run in 2020. And as more women win and run for office at the state and local level, the national pipeline fills up.

The growing presence of women is more than symbolic. When women are involved in policymaking, “the agenda changes,” says Rosa DeLauro, who’s represented Connecticut’s 3rd District since 1991. Plenty of studies show that women—especially Democrats and moderate Republicans—sponsor more bills than their male colleagues on education, health care, violence against women, and abortion (both for and against). They also bring women’s perspectives to existing policy debates, as when Debbie Stabenow, the senator from Michigan, pushed for maternal health coverage in the Affordable Care Act.

Americans also like to think that women are better at getting things done. According to the Pew Research Center, 42 percent believe that female politicians are better at working out compromises. Surveys of women in Congress have found that female representatives consider themselves better collaborators, too. Women “make our government better,” says Deborah Pryce, one of three Republican women elected to the House in 1992. “They’re just better at getting to the bottom line faster in a more bipartisan way.”

The research tells a different story. One 2016 study that looked at 20 years of congressional data found “no support for the hypothesis that women are inherently more willing to compromise.” The study determined that only Republican women were more likely to reach across party lines to co-sponsor bills, particularly those that focus on health, education, or social welfare. And the trend had more to do with the ideology of the women elected than their gender, the researchers found. Women tend to occupy the leftward wings of their respective parties. In other words, Republican women are more likely to seek common ground because they tend to be moderate. “Women don’t vote all together. They don’t vote along gender lines,” says Kelly Dittmar, a scholar at the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. “They vote along party lines.”

In other words, gender isn’t a bellwether; women, like men, are partisans first—especially in this climate, says Michele Swers, a professor of American government at Georgetown. “You have to be able to get elected.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Janet Paskin

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.