El Salvador’s Reformist President Takes an Autocratic Turn

El Salvador’s Reformist President Takes an Autocratic Turn

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In early February, soldiers and police in riot gear barged into the legislature in San Salvador. Lawmakers sat in shock, and the new president, who brought the troops in, warned them, “I think it’s clear who has control of the situation.” Even veteran observers of Central America were confused. What was happening?

Until then, El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele had been hailed by the Trump administration and U.S. investors as one of the most promising young leaders in the developing world. He is 38 and, until now anyway, seemed savvy, gutsy, and impatient for reform. Bukele said Salvadorans were fleeing to the U.S. because previous governments had failed them. Don’t send more aid, he implored America. Invest in our country so we can create jobs and bring our people home.

Bukele seemed to know just what to do to make American officials sit up. He named a youthful cabinet, half of them women. He got China to promise to build sewers and roads to the country’s undeveloped black-sand Pacific coast for a tourist destination he’s already designated Surf City. Before his debut speech at the United Nations in September, delivered tieless, he snapped a selfie at the podium and posted it to Twitter. And he was getting quick results. Homicides, a toxic challenge in the gang-infested country, were down 60% from when he took office in June; emigration had dropped by half. The U.S. State Department reduced the country's risk assessment from level 3 to 2, putting it on a par with Mexico and some European countries.

Then came Sunday, Feb. 9. While much of the country was watching the Oscars, El Salvador’s legislative assembly was surrounded by tens of thousands of Bukele supporters and security forces, including snipers on the roof. The president said that lawmakers had been slow-walking approval of a $109 million loan to beef up security services. (Bukele’s security budget, the largest in the country’s history, had already been passed; this was a supplemental request.) It had been more than three months, and, by his calculation, every day meant more deaths on the streets. He demanded an extraordinary legislative session for that Sunday; the lawmakers said they’d meet on their schedule, not his. He summoned his followers and mobilized the military and police, sending troops to knock on legislators’ doors. After entering the assembly and praying for three minutes, he left and took the troops with him. God, he said, had urged him to be patient.

Human rights groups, opposition leaders, major newspapers, and governments, some of whom had welcomed Bukele’s election, condemned his move as an assault on democratic norms. U.S. Ambassador Ronald Johnson, who’d thrown his weight behind the new president, posting photos of their families vacationing together, tweeted disapproval.

After the military intrusion, two lawmakers went to the Supreme Court, which told Bukele to back off while it examines the case. He agreed, but he’s kept up a steady stream of speeches, op-eds, and tweets justifying his move against the “corrupt” and “crooked” congress he hopes to replace in elections in February 2021. (The party he founded, Nuevas Ideas, has no representation in the 84-member legislature, though it has a handful of sympathizers.) Earlier this month, in keeping with his penchant for big gestures, Bukele imposed the western hemisphere's first ban of foreigners entering the country and ordered a 30-day quarantine on locals returning from abroad to curb the spread of coronavirus despite there being no confirmed cases.

Bukele is the first president in three decades from neither of the two sides that fought in the vicious civil war of the 1980s, Arena on the right and FMLN on the left. His arrival seemed to augur an important new era of cooperation with Washington and the start of economic policies relying far less on remittances from those who’ve left and more on jobs and infrastructure built at home, as Bukele said he wanted.

The military action in the legislature embarrassed some of Bukele’s supporters, who argue that the president isn’t a would-be dictator but simply a young man who lost his cool. “We need to see this in the right context as a mistake and turn the page,” says Francis Zablah, a parliamentarian who was in the legislature that day and still has high hopes for his country under Bukele.

Carlos Dada, who founded the Salvadoran investigative journalism site El Faro a quarter century ago, is far more worried. “When Bukele came to power, he ended the old political system. We hoped he’d unify the country. Instead, we now have a state centered around one man.”

Bukele, who declined an interview request, has cast himself as a Trumpian outsider vowing to drain the swamp in the Massachusetts-size country, where a dozen or so old families still control most of the wealth. He comes from the large Palestinian Christian community that settled here a century ago. Bukele’s father, Armando, was an iconoclastic intellectual and businessman who converted in adulthood to Islam and then set up an ecumenical council of religious leaders. Nayib, said by family friends to have been his father’s favorite of 10 children, showed an early interest in politics but had little patience for academics. After two semesters of university, he dropped out, investing with a friend in a discotheque.

Bukele started his political career in 2012 as mayor of a small town outside San Salvador and was later elected mayor of the capital. In addition to playing a key role in rebuilding a central park, he focused on youth rehabilitation and job training. He began in the leftist FMLN, which then held the presidency of the country of 6 million. He started moving to the center, and when the party didn’t trust him to be its candidate to replace President Salvador Sánchez Cerén, he ran on his own. Many dismissed the candidacy as chimerical, but he won in a landslide.

Polls show his support remains at 90%. He is dismissive of the media, the legislature, and the moneyed establishment, relying on popular support and the military. His most fervent followers appear at rallies holding aloft black crosses, often labeled with the word “legislators.” Some add a poop emoji.

Bukele and his wife, Gabriela, are now the nation’s dominant figures. Large color portraits of them hang in every government building. A police commander in northern San Salvador, pointing to the portraits, says this is the first government that’s required him to hang such pictures in his office.

Behind Bukele’s appeal is a dire economic situation. Every year, 60,000 Salvadorans enter the workforce, while 5,000 jobs at most become available, according to the Fundación Salvadoreña para el Desarrollo Económico y Social, or Fusades, a conservative think tank. The 55,000 who don’t get work have three options: enter the informal sector, meaning street sales and off-the-books labor (almost three quarters of economic activity); join the 2 million Salvadorans living in the U.S.; or affiliate with one of the gangs, which together count as many as 70,000 members. Most of the gangs were formed in Los Angeles. The two biggest are MS-13 and M-18. When members were deported from the U.S. in the 1990s, they took over swaths of territory, overwhelming local security services.

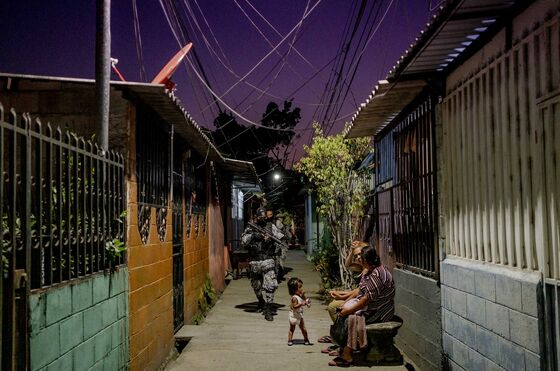

Many of the country’s killings are gang-related and linked to extensive extortion rackets. Huge numbers of businesses pay gangs daily or monthly fees to be left alone. Homicide in El Salvador has been dropping steadily for the past few years, especially in recent months. During 2015 and 2016, there were 17 or 18 murders a day; in February 2020, the least violent month in decades, there were fewer than four, on average. But how much credit Bukele deserves is a matter of debate.

His chief of police, Mauricio Arriaza Chicas, said in an interview that the last time there was a decline in killings was in 2012 when the FMLN government cut a truce with the gangs. The deal included privileges for gang leaders in prison (strippers, food delivery, Wi-Fi). When the truce collapsed a couple of years later, the country saw its worst homicide rate ever in 2016—more than 100 per 100,000, making it the equivalent of a war zone.

Under Bukele’s crackdown, gang members in prison have been cut off from members on the street to reduce their power. Police have been provided with new protective gear and boots, equipment has been improved, and saturation policing, in which security forces focus on trouble spots, has become widespread. It seems to be working, but some people say the problem has shifted, and the police aren’t adjusting rapidly enough. Paul Consoli, a U.S. military and law enforcement intelligence specialist who works as a consultant in El Salvador, says he’s seen data suggesting the gangs have grown more sophisticated in their extortion schemes. They’re buying up private security firms and using them to collect money, reducing their need to kill while preserving the outlaw nature of the society. The homicide decline, he worries, hides the truth.

A year ago, President Trump cut off about $500 million in aid to all of Central America, complaining that governments weren’t doing enough to stop migration into the U.S. Aid has started to flow back, but the stoppage has complicated Bukele’s efforts. In some fashion, all of the country’s problems—emigration, violence, drug trafficking, underdevelopment, and corruption— have U.S. ties, and American investment is therefore seen as central to its success. As Foreign Minister Alexandra Hill says, “El Salvador is now open for business, and the U.S. is priority Nos. 1, 2, and 3.” After he was elected, Bukele cut ties with Nicolás Maduro’s government in Venezuela and promised to be careful about Chinese investments, actions that seemed designed to please the U.S.

The American Embassy has reciprocated, encouraging investment in textiles and services. It’s also helped build up the country’s modest tourism industry by sending delegations to and from Hawaii and California. Orlando Menendez, co-owner of Puro Surf, a boutique hotel in the beach town of El Zonte, says Bukele is the first president to understand the value of the sport to the country: “As others have said, if you want to stop emigration to the U.S., don’t build a wall. Make jobs.” On Mar. 12, Moody's Investors Service upgraded the country's rating from stable to positive, saying business conditions had improved and government liquidity risks had declined.

One significant resource for El Salvador is an American named Howard Buffett, son of Warren. A farmer and former Archer Daniels Midland Co. executive who has a foundation that 15 years ago got involved in helping with water and crops in Central America, Buffett became friendly with a Salvadoran farming family. When he was visiting several years ago, they told him they couldn’t bring crops to market without paying protection money. “They had a line of trucks outside, and the gangs came up and said they have to pay $100 a month or they’ll kill their drivers,” Buffett recalls. “We realized we were missing an important aspect. Rule of law has become the most critical piece to success.”

Buffett shifted his focus in El Salvador to law enforcement, buying equipment for the police and pledging $25 million for a top-of-the-line forensics lab and database that’s already being built. He met Bukele when he was mayor of the capital and liked him immediately. The American played a key role in rebuilding Cuscatlán, San Salvador’s central park. Once filled with trash and frequented by drug dealers, it reopened in September after a $22 million makeover. Now it’s an exceptionally welcoming space for mothers and children, with art displays and free courses in music, English, and yoga.

Bukele’s decision to bring the military into the legislature on Feb. 9, Buffett hopes, was a bad call by Bukele and not part of a pattern.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.