For Fed’s Disaster Junkie, Pandemic Was One of 99 Bad Scenarios

For Fed’s Disaster Junkie, Pandemic Was One of 99 Bad Scenarios

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- A red alert sounded at the Federal Reserve in mid-March when Americans began pulling out of prime money-market funds, one of the safest places to park cash. As policymakers cut interest rates to near-zero, it quickly became clear that they’d need to get creative, and fast, to prevent a shutdown in the flow of credit.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his board called on Andreas Lehnert and his 50-person team at the Division of Financial Stability. Known as FS inside the Fed system, this crew started in 2010 with a staff of just four, set up in the aftermath of the financial crisis. The division spent much of the ensuing decade looking at fragilities in the financial system that could lead to a full-scale breakdown in moments of stress. So when Covid-19 hit and widespread lockdowns of every type of business threatened a sudden halt in the flow of money, Lehnert and his colleagues were prepared.

“Chair Powell’s instructions to us were that the system is going through a world historical crisis,” so the response needed to be commensurate, says Lehnert. The marching orders were “pretty crisp and clear,” he says: Try to avert permanent job losses as the economy went through a slide in activity, before the eventual rebound. “We sketched out what is every job that is out there,” he says, “and what would be a facility that would address those employers.”

Just two days after the Fed cut its benchmark rate to near zero in a hastily convened Sunday meeting on March 15, it rolled out the first of the programs that Lehnert and his colleagues had developed. By the end of the month, most of what would eventually total nine separate facilities—lending programs—had been unveiled, providing backstops for everything from the corporate bond market to money market mutual funds to companies selling short-term securities to manage their cash flow. While some of the lending programs have had a slow start, nobody is suggesting that they’re no longer needed.

The plans were coordinated from a makeshift office Lehnert set up in his suburban Virginia home. Often fueled with oatmeal and almond butter and keeping alert by means of caffeine, pushups, and hilly runs, the 51-year-old starts his work day around 7 a.m. and ends it late at night. The soundtrack from the musical Hamilton is usually playing somewhere in his house as he works. His wife reminds him to air out his room, which he likes to keep toasty.

Lehnert’s home bookshelf betrays his professional obsession with “what could go wrong.” He’s read about why planes crash, why nuclear plant accidents run out of control, and why the space shuttle Challenger blew up. There’s Why Buildings Fall Down and Plagues and Peoples, perhaps especially pertinent for 2020. Lying for Money seems another useful read for someone in Lehnert’s line of work.

He says a common thread in disasters is that even experts can miss the totality of what’s happening. “They don’t understand where they are” when something goes wrong, he says. “They had a bad process for understanding the behavior of the system as a whole.”

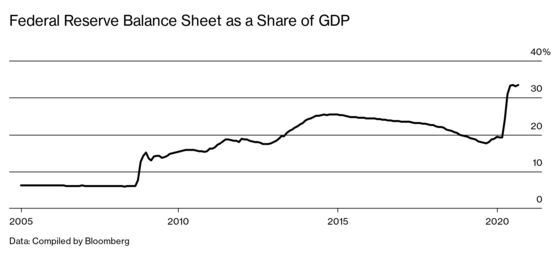

While Powell highlighted in a Sept. 16 press briefing that the U.S. job market faces a long road to recovery, with 11 million Americans yet to recover jobs lost during the pandemic, the threat of a financial collapse has receded with the central bank’s broad safety net. Now some observers are looking for the seeds of the next crisis—all the more so since the Fed in August adopted a long-run strategy of letting inflation exceed its 2% target to make up for earlier undershooting, which implies that the central bank would allow the economy to run “hot” for a while. Fed officials on Sept. 16 projected they won’t boost rates through 2023.

Cheap money has a way of fueling speculation, excessive borrowing, and soaring stock prices, along with amnesia about risks. The last expansion witnessed a Bitcoin bubble, a buildup of leveraged bets in the Treasury market, and a surge in high-risk corporate loans. Powell and the other members of the decision-making Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) are relying on Lehnert and the FS team to keep on top of potential dangers.

“Of course we monitor financial conditions very carefully,” Powell said in his Sept. 16 remarks. “We look at it through every perspective. The FOMC gets briefed on a quarterly basis.”

That briefing, known internally as the Quantitative Surveillance, or QS, report, comes from Lehnert and his team. It often focuses on special topics, such as particular hedge-fund strategies, potential weaknesses among mortgage servicing companies, vulnerabilities in structured loans—securities made up of repackaged debt—and the risk of disruption in bond trading. Because FS is relatively small, Lehnert relies on specialists from across the Fed system to help produce the QS.

“They are always looking to identify that transmission channel or amplification mechanism that we just haven’t thought about,” says Lael Brainard, the Fed governor who oversees Lehnert and the FS crew and who spends 90 minutes each day on calls with them, which she notes is a reduction from earlier in the year. While the staff evaluations are “never going to forecast the risks exactly right,” the analysis is focused on that possible amplification of problems, she says.

Lehnert draws on his voracious reading to help imagine what could happen. When he was a grammar-school boy in Oklahoma, his parents inspected his backpack in the morning for books he might be sneaking out of the house that could distract him from his classwork. When that didn’t work, they started locking up the books. One day they came home and found young Andreas reading the phone book.

It was a magazine, and its title, that inspired his choice of career. His parents brought home an issue of the Economist when he was about 15. After reading it from cover to cover, he decided that’s exactly what he wanted to become. He went on to earn a doctorate in economics at the University of Chicago, a school known for its faith in markets. He took classes from some of the world’s most influential economic thinkers, including Nobel laureates Robert Lucas Jr., James Heckman, and Thomas Sargent.

Lehnert also draws on his experience in the runup to the last financial crisis—the unprecedented explosion in high-risk mortgage lending of the mid-2000s—which almost brought down the global financial system. Seven years into his career at the Fed, Lehnert in June 2005 was tapped to make a presentation to the FOMC on the housing market. One gauge of home prices had just risen 16% from the year before even as the Fed started raising rates from historic lows. As many others concluded at the time, there was little systemic risk, he argued.

“Institutions with large amounts of mortgage credit risk on their portfolios are well-positioned to handle severe losses,” Lehnert said then. “Neither borrowers nor lenders appear particularly shaky. Indeed, the evidence points in the opposite direction: Borrowers have large equity cushions, interest-only mortgages are not an especially sinister development, and financial institutions are quite healthy.”

After a caveat, his bottom line was: “The national mortgage system might bend, but will likely not break, in the face of a large drop in house prices.”

That proved to be a failure to extrapolate the implications of a rapid evolution of the mortgage market and how securitization of low-quality loans could go on to threaten the financial system itself. “We didn’t understand the amplification mechanisms,’’ Lehnert says now, noting that he often thinks of that 2005 episode. “It is a muscle that we are exercising all the time now.”

He encourages his group—including Michael Kiley, who previously led the Fed’s economic modeling team, Elizabeth Klee, an expert in the payments system, and chief of staff Nami Mukasa, an investment banking veteran—to think beyond the standard framework of analysis. He calls the FS division a “home for people that don’t think just about what is in front of them.” And he values “thinking creatively about risks that we haven’t seen or haven’t worked in,” rather than chasing the market move of the day or getting trapped into debates over whether there’s a bubble in some asset.

“We have spent many years thinking about events that were unlikely, improbable, and, frankly, weird,” says Lehnert. There was even a brief consideration of how a short, sharp recession caused by a pandemic would affect the U.S. financial system.

“Ninety-nine percent of them never came to pass,” he says.

Until one of them did.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.