The U.S. Maker of Fake Mayo Pitches China on Fake Eggs

The U.S. Maker of Fake Mayo Pitches China on Fake Eggs

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On a recent Monday morning in a Shanghai conference room, four executives from a major Chinese food producer and distributor sat socially distanced from one another, pulled down their masks, and tried some fake eggs. In a makeshift basement office in San Francisco, 15 hours behind, Josh Tetrick, the chief executive officer of egg-substitute maker Eat Just Inc., watched via Zoom. His head chef in China presented the Shanghai execs with eight ways to serve the ersatz ovum, Just Egg, which is made primarily from mung beans. The hope was that one would be tasty enough for the Chinese company to sell online and at fast-food chains.

The eight options included Tetrick’s two favorites. The Inside-Out Egg is a faux omelette stuffed with lettuce, a hash brown patty, and spicy mayo; the Pinwheel Egg is essentially a fake-egg burrito with rice, fried onions, and pickled radishes. Both bombed. Still, the pitchees picked a winner, and while Tetrick stresses that no deal has been signed—hence the anonymity—he says Eat Just, better known as Just, is moving on to the next round of talks.

Although the negotiations have taken more than three years, things sped up over the past several months, Tetrick says. “Because of what’s happening around Covid,” the CEO says with uncharacteristic understatement, “there’s been a notable change about how consumers are thinking about food.”

Last year, Beyond Meat Inc.’s initial public offering and Impossible Foods Inc.’s bleeding beefless Whopper helped bring plant-based meat to 51% of American lips, according to research firm Piplsay. Before the pandemic, the emerging industry had set its 2020 sights on China, where plant protein has been a staple for a millennium but meat imitations are just getting started. Regional plant-protein makers have made inroads in Hong Kong, but most of China is largely unclaimed territory for mass-market fake meat. Just, however, is already there.

Tetrick’s company says it’s sold tens of thousands of bottles of its liquid formula in China over the past year, mostly via shopping sites owned by internet giants Alibaba Group and JD.com, as well as in a handful of retail stores, restaurants, and hotels. The numbers don’t exactly herald a revolution—the company says a good day on the Alibaba and JD sites means 1,300 bottles sold—but the early move into China has positioned the American company well, says Sean O’Sullivan, managing partner at venture capital firm SOSV. (The firm invests in plant-based protein makers but hasn’t invested in Just.) Tetrick’s company, valued at $1.2 billion, has raised $300 million in venture funding and says it’s sold the equivalent of about 40 million fake eggs, mostly in the U.S.

All this may surprise people familiar with the company under its original name, Hampton Creek. Founded in 2011, Hampton Creek established itself as a purveyor of vegan mayo, but became best known for its scandals, some of them first revealed by Bloomberg Businessweek. In 2016 the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and Department of Justice opened investigations into possible fraud and other securities violations after Bloomberg reported that Tetrick’s team was buying up its own products, making investors and potential partners think the mayo was more popular than it really was.

The company denied wrongdoing, and shortly after Donald Trump became president, both agencies dropped their investigations without finding any violations, but by mid-2017, everyone on the board besides Tetrick had stepped down. Asked about that, Samir Kaul, a former director who says he remains on good terms with Tetrick, says, “I would rather just focus on the positive.” Kaul, a founding partner at VC firm Khosla Ventures, says he doesn’t regret his early half-million-dollar investment in Tetrick, even though it was based on a largely aspirational PowerPoint slideshow. “I think it’s really important to have big setbacks, you become smarter and stronger,” he says. “Now he’s taking a much more humbled approach.”

Tetrick says he takes responsibility for the buybacks, blaming his inexperience. (It wasn’t exactly a case of youthful naivete; in 2016, he turned 36.) “I am definitely better than when I started—that wasn’t a very high bar,” he says. “I wish I was a lot better than I am right now.”

Anyone who’s seen a pile of Beyond Meat patties sitting in an otherwise empty freezer case during the pandemic has reason to doubt that the fake meat revolution is truly nigh. In a panic, people want staples and familiarity. Yet as prices on the substitutes get more competitive, real meat’s advantages may be narrowing, especially now that African swine fever has cut China’s pork supply and some key U.S. slaughterhouses have sustained Covid-related closures. A shift toward “safer meat alternatives” is coming, says Alex Frederick, a senior analyst at market researcher PitchBook. Sales growth in the category has continued to rise during the pandemic.

For years, Tetrick and his company were willing to sort of make it up as they went along, and to exaggerate just how prepared they were to step up. Hampton Creek was founded on the promise of vegan egg substitutes. But in 2013 it retooled its operation to focus on vegan mayo, a product already familiar to plant-centric eaters, at the request of Whole Foods. (Whole Foods couldn’t confirm the specifics of these negotiations but says the dates line up with when it began selling the mayo.) Tetrick now calls it a “very random, unintentional first product.” The mung eggs finally reached mouths at the end of 2017, after the mayo had become a punchline.

Before the pandemic hit, Just Egg was sold in about 10,000 U.S. supermarkets and 1,000 restaurants. It’s available either as a $5 to $8 liquid that can make about eight eggs’ worth of scramble poured into a frying pan, or as a roughly $7 set of four frozen, pre-folded servings that can be easily made into breakfast sandwiches. Both versions taste more like eggs than a Beyond Burger tastes like beef, which is to say, almost but not quite. While Just’s restaurant business has all but flatlined during the pandemic, Tetrick says about three-quarters of the company’s revenue came from retail grocers before the time of corona and that it sold 78% more bottles of Just Egg in May than in February.

Tetrick’s plan for international expansion depends on local partners, who will be expected to mix Just’s mung protein with oil, water, and other ingredients, then bottle and ship the products. The CEO cites Coca-Cola Co.’s syrup distribution network as an inspiration and says current board member Jacob Robbins, a former Coke supply chain executive, persuaded him to outsource distribution and the final stages of production.

As the pandemic spread in March, Just announced new partners, including Betagro Group, a major food company across Asia, and South Korean giant SPC Samlip, which franchises fast-food chains including Shake Shack, Dunkin’, and Paris Baguette. Covid permitting, they could start delivering Just Egg products to as many as 4,000 stores and restaurants later this year. Just is also working with Eurovo Group, a European egg producer, though regulators there have yet to approve the mung protein for consumption.

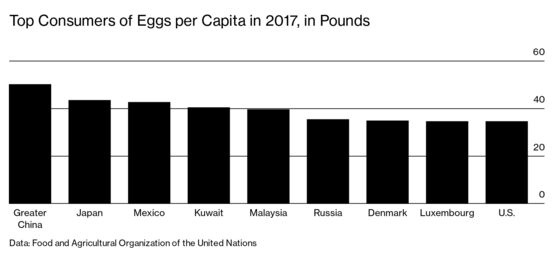

Like meat substitute makers, Just’s biggest challenge is price. In China, an egg typically costs about 14¢, lower by an order of magnitude than a comparable amount of Just Egg mixture costs. Markups on the Alibaba and JD sites often almost double the price of a bottle to about $14. Despite what a spokesperson for Alibaba’s site Tmall called strong interest, this makes the product, as JD said in an email, “prohibitively expensive for most consumers who are not white-collar workers in first-tier cities.” A Just spokesperson says that the company is trying to set up large-scale protein processing facilities in Asia to help bring prices down and that recent research and development efforts will help, too, by separating the key proteins from the mung beans more efficiently.

The degree to which Tetrick waves away some of these key issues, while stressing he’s working on them, raises the question of how much his overpromising has changed since the mayo. Just has said for several years running that it would bring its lab-grown chicken nugget to market in a matter of months, but regulators still have yet to sign off on the technology’s safety. Even if Covid were to change China’s animal protein consumption, something SARS, H1N1, and avian flu failed to do, mung bean-based eggs “wouldn’t take long to copy,” says Helen Hae-Ryoun Gi, a partner at Hae Creative, a consultancy in Seoul that advocates for new plant-based foods in Asia.

Still, Just is an early mover, and Tetrick says “there’s plenty of room” for competition. The more supply chains reorient around plant-based proteins, he says, the easier his expansion will be.

For now, he says, he’s focused on perfecting the third iteration of Just Egg, due out later this year. Fifteen of his 155 employees have been sheltering in place with a company-provided Thermomix, several versions of the mung protein, and various gels and spices to refine the formula from their homes. The new version, Tetrick says, will be creamier, with a richer mouthfeel and fewer notes of, well, mung bean. Samples weren’t forthcoming.

Read next: How Advanced BioCatalytics Pivoted to Coronavirus Cleanup

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.