Alzheimer’s Trials Exclude Black Patients at ‘Astonishing’ Rate

Alzheimer’s Trials Exclude Black Patients at ‘Astonishing’ Rate

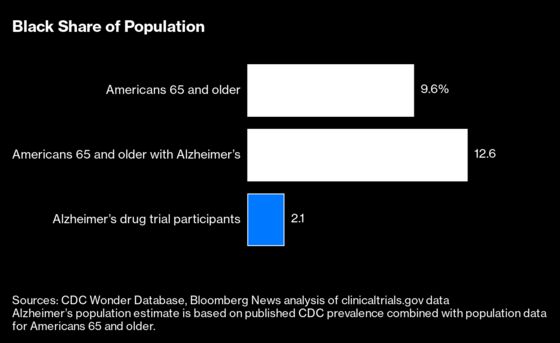

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Black people are about twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease as White people, but for years the pharmaceutical industry has mostly left them out of trials intended to prove new drugs are safe and effective.

Brian Van Buren, a 71-year-old retired flight attendant, knows what that feels like. He’s been living with Alzheimer’s since 2015. Over the years he has tried to join numerous trials, but he says he’s been turned down every time. In some cases he’s been told his other health issues—he suffers from diabetes, hypertension, and sleep apnea—rule him out. At other times, he says, he was turned away for not having a nearby partner or caregiver.

“I have been rejected for every trial,” says Van Buren, who is Black.

A Bloomberg News analysis of 83 Alzheimer’s disease drug trials shows Van Buren is no anomaly: Only 2% of patients included in trials reported in the past decade were Black. Bloomberg’s analysis of minority enrollment looked at more than 50,000 participants in drug industry and government-sponsored trials to treat or prevent Alzheimer’s whose results were posted on the government website clinicaltrials.gov or published in major medical journals.

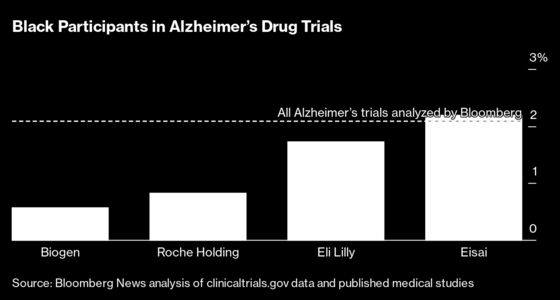

Two trials organized by Biogen Inc. for its drug Aduhelm, the first Alzheimer’s drug approved in almost two decades, were among those with the lowest Black representation. Only 19 people, or 0.6%, of 3,285 participants in its two final-stage trials identified themselves as Black. According to government statistics, 9.6% of Americans 65 and older are Black.

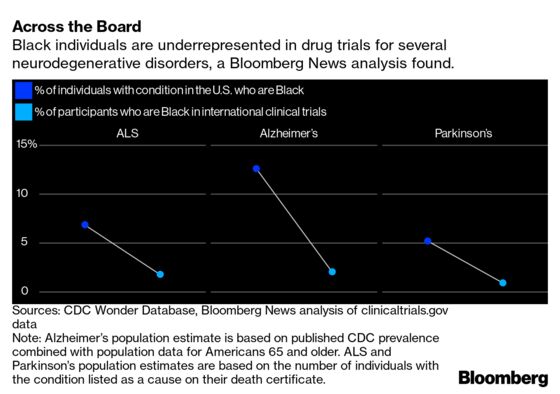

A lack of Black representation is “astonishing but entirely typical for industry-run Alzheimer’s trials,” says Jennifer Manly, a neuropsychologist at Columbia. Although scientists have been aware of the problem for years, she says, she hasn’t seen evidence that drug companies are making the kind of wholesale changes that would fix it. Bloomberg’s analysis shows similar results for more than 90 trials of drugs for Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), though these illnesses appear to be somewhat less common in Black people relative to White people.

Biogen’s chief medical officer, Maha Radhakrishnan, acknowledges that diversity wasn’t a focus when the company began studying Aduhelm, but she says the company is making a concerted effort to improve. It’s vowing to enroll 18% Black and Latino patients in the U.S. in a new trial of Aduhelm that’s been mandated by the Food and Drug Administration. It’s set to begin next month but won’t produce results for years.

There are good reasons to study Alzheimer’s in broader populations: The disease is still poorly understood, and the brain pathology and disease genetics may be different in groups with different ancestry. “We’re not just trying to get a representative population because it’s a nice, politically correct thing to do,” says Stephanie Monroe, executive director of AfricanAmericansAgainstAlzheimer’s, part of the nonprofit UsAgainstAlzheimer’s. “Drugs will work differently in different populations.”

Alzheimer’s and other brain-wasting diseases have emerged as a new frontier of medicine. The FDA approved Aduhelm in June amid controversy over its efficacy, and similar drugs are in the late stages of trial. A drug that works even modestly well for Alzheimer’s could reap many billions of dollars in sales, with the Black population potentially accounting for an important portion of the market. The Alzheimer's Association estimates that older Black people are about twice as likely to have Alzheimer's or related dementia as older White individuals. And in a study of more than 1.8 million older people treated at Veterans Health Administration medical centers, Black veterans were 54% more likely to be diagnosed with dementia over about 10 years than White veterans, while Hispanic patients were 92% more likely to develop dementia, according to results published in the Journal of the American Medical Association on April 19th.

Bloomberg’s analysis also found very low representation of Hispanic people in trials of Parkinson’s disease drugs. Critics contend doctors can’t possibly know the safety and efficacy of new drugs among diverse populations if drug trials include few of them. Black individuals, for example, are more likely to have a gene called APOE4 that predisposes people to Alzheimer’s as well as side effects (including brain swelling) of some Alzheimer’s drugs. In the U.S., Black people are also more likely to have preexisting conditions such as diabetes and vascular conditions that could affect how the drugs work.

Some researchers argue that by focusing on one cause of Alzheimer’s disease, a faulty protein called amyloid, the industry is tilting research toward healthier, more affluent White people. Screening for some trials tends to filter out anyone with various preexisting conditions. That filter may rule out certain people who have had strokes or uncontrolled diabetes, conditions that tend to afflict Black people at higher rates than White people. In most Alzheimer’s drug trials, “we are treating a type of Alzheimer’s disease that only affects a privileged few,” says Jonathan Jackson, a neuroscientist at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Community Access, Recruitment & Engagement Research Center, which studies trial diversity.

In addition, researchers tend to look for people who have received an early diagnosis of the disease. That factor favors affluent patients who have easier access to specialists and screening at a relatively small number of top medical centers. Monroe has personal experience of this: Her father, who is 86 and has Alzheimer’s, didn’t get a clear diagnosis until five years after his symptoms began, she says, and by that time it was too late to join most trials. In any case, she says, he was never asked. “Anyone who isn’t wealthy and White gets diagnosed much later, so they don’t even have a chance to be eligible, much less participate,” Jackson says.

The failure to get more Black people into trials could add to long-standing skepticism over laboratory science and drug industry trials among some in the Black community, who point to historic abuses such as the infamous Tuskegee experiments, in which poor Black men with syphilis were left untreated. Wariness of the medical establishment among Black Americans has also contributed to vaccine hesitancy, which may have worsened many people’s vulnerability to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Pressure for change is mounting.

In a decision on April 7, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sharply restricted Medicare coverage of Biogen’s Aduhelm, citing its potential side effects and unproven efficacy. Significantly, as part of that decision, the body also noted the lack of diversity in trials of Alzheimer’s drugs. The Alzheimer’s Association is pushing for legislation that would create more federally funded Alzheimer’s research centers at hospitals in areas with high concentrations of underrepresented populations.

“The No. 1 reason people don’t participate is they don’t know about the studies,” says Jose Luchsinger, a professor of medicine at Columbia. In 2012 he led a trial whose enrollment was one of the most diverse examined by Bloomberg, with almost one-third of the participants identifying themselves as Black. To attract patients, Luchsinger visited local senior centers, community organizations, and churches in neighborhoods around the university, including Harlem, to talk about mild cognitive impairment and tell people about the trial. Columbia offered free car service to the university, including appointments on weekends for patients who couldn’t take time off from work or cared for grandchildren during the week.

“This is something we’ve struggled with as an industry,” says Stacey Bledsoe, a nurse who’s part of a newly formed team aiming to improve clinical trial diversity at Eli Lilly & Co. “If we have 12.5% of African Americans with Alzheimer’s disease, we should have 12.5% of patients that are of African-American descent in our studies.”

Van Buren says drug companies might have kept out people like him because their trials can exclude those with preexisting conditions that may be more common in older Black people. Researchers are only beginning to study the impact of complicated trial rules, but one analysis by researchers at the National Institute on Aging found that 142 of 235 government-sponsored Alzheimer’s and dementia trials contained at least one exclusion criterion that could disproportionately affect Black or Latino individuals.

Some psychological tests that are designed to spot subtle signs of mild cognitive impairment were created based on responses from “highly educated White people,” says Reisa Sperling, a neurologist at Harvard Medical School who leads a big Alzheimer’s prevention trial called A4. That bias may throw off the scoring when people with different cultural or educational backgrounds take them, resulting in some people being inaccurately classified as being too impaired to join a trial, she says. In the A4 trial, more than 30% of Black people screened for the trial were excluded because they didn’t meet cognitive test criteria, compared with only 16% of White people.

Finally, Alzheimer’s trials are by necessity time-consuming, involving numerous in-person scans and infusions. They often require a partner or caregiver to accompany those joining a trial. That complication could discourage economically stressed families from joining a trial and favor those who are more affluent and have resources and time to accompany their loved ones to doctor’s visits and tests, often in distant cities.

Van Buren, who is gay, says that the partner requirement also discriminates against many older LGBTQ people who live alone. “It eliminates a large percentage of the gay population,” he says. Van Buren lives alone with his dogs, and his partner resides most of the year in Brazil.

Drug companies are getting the message. Biogen is setting aside dedicated funding to help hospitals and clinics reach out to underserved communities. And in choosing trial sites, it’s carefully reviewing local demographics to make sure it has sufficient locations near where people of color live. “We take this very seriously,” Chief Medical Officer Radhakrishnan says.

Biogen’s partner, Eisai Co., says that its Phase III trial of an experimental Alzheimer’s drug called lecanemab, taking place now, was able to enroll 4.5% Black individuals and 22.5% Hispanic individuals in the U.S. portion of the trial, up from the numbers it achieved in its second-stage trial.

Roche Holding AG and Eli Lilly are also working on late-stage drug trials targeting the same brain protein. Roche says it’s making extensive efforts to increase diversity of its ongoing Alzheimer’s trials, including adding transportation and more reimbursement for trial-related expenses.

Eli Lilly is turning to mobile RVs to enroll people who don’t live near big research hospitals. The company has also found that increasing the number of minority doctors involved in its trials has helped recruit more diverse patients. But there’s still a way to go. In one ongoing Lilly trial, only 12% of Black and Hispanic patients who volunteered met eligibility criteria, compared with a much higher 30% of non-Hispanic White and Asian patients, according to data the company presented at a recent medical meeting.

Drug companies have said that their large trials are conducted in numerous countries and may enroll substantial percentages of patients from countries with few Black residents, which could skew diversity representation lower overall. Bloomberg was not able to perform an analysis of U.S.-only enrollment by race, which is not reported for many trials. For the large Alzheimer’s trials that reported country-specific figures, 48% of the patients were from North America.

Van Buren, turned down for so many trials in the past, says he’s given up trying to join a study. He’s come to the conclusion that the rules discriminate against people like him. “I don’t expect to be living that much longer, so why prolong it?” he says. “I have done everything that I have ever wanted to do in life.”

Data Analysis Methodology: Bloomberg extracted enrollment demographics for drug trials for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, SMA, and ALS from clinicaltrials.gov. The analysis included Phase II and Phase III trials with 50 or more patients for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, and 10 or more patients for SMA and ALS. Trials of drugs or supplements to treat or prevent the diseases or related symptoms were included. Safety extension trials and studies of diagnostic imaging agents were excluded. The analysis also included newly approved drugs listed in the FDA’s Drug Trials Snapshots and in major published trials of amyloid drugs for Alzheimer’s. In total, data from 180 trials were analyzed, including 83 Alzheimer’s trials, 58 Parkinson’s trials, 27 ALS trials, and 12 SMA trials. Missing demographic data was counted as “unknown or other.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.