In Role Swap, Trump Runs as an Outsider, Biden Plays Incumbent

President Donald Trump, the incumbent, and Senator Joe Biden, his challenger, have effectively swapped roles.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Over the past several months, a presidential race already upended by a global pandemic and historic recession has developed an odd characteristic that’s making it even more unusual: President Donald Trump, the incumbent, and Senator Joe Biden, his challenger, have effectively swapped roles.

The sitting president is campaigning like an outsider, lobbing incendiary tweets and blaming others for the failures of the government he himself presides over. Biden, meanwhile, is acting like a traditional incumbent, running on his record and the promise of familiarity.

Trump isn’t doing much of what a typical incumbent does in an election year. He hasn’t rolled out an ambitious second-term agenda. He doesn’t make a big show of trying to unify the country. He isn’t using the White House Rose Garden to host foreign dignitaries or captains of industry—unless you count the MyPillow TV pitchman, Mike Lindell—to showcase the powers of the presidency and remind people what he can do for them.

With the lockdown lifting, he’s finally been able to make use of Air Force One, making swing-state campaign stops in Arizona and Wisconsin. But by focusing unwaveringly on his base, he isn’t doing the one thing presidents in both parties have always done when seeking a second term: making a concerted play for undecided voters in the middle.

“One of the great myths of the 2004 campaign was that President Bush just appealed to his conservative base,” says Sara Fagen, former White House political director and senior strategist on George W. Bush’s reelection campaign. “The fact is, our whole focus was on the winning over the middle.”

For Bush, running in the wake of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, that meant emphasizing national security and American safety. “We knew that even people who didn’t completely agree with him or love his economic policies felt more secure with him at the helm,” Fagen says. “It came up in our research and fit the president naturally.”

Barack Obama, whose reelection race more closely resembles the current one, had to persuade voters to look past a tough economic climate and stay the course despite high unemployment. “What we were trying to do was sell a story of where we were going,” says Jim Messina, Obama’s 2012 campaign manager. “We talked about a jobs plan, we talked about economic recovery, because we had to persuade voters in a tough economic time that things were getting better, and we never wavered from that theme.”

Trump has mostly shunned the approach his predecessors employed. He had to abandon his campaign theme (“Keep America Great”) when the coronavirus took the shine off the economy, and he hasn’t settled on a replacement. He rarely touts his main legislative achievement, the 2017 tax cut. Even before the pandemic he showed no inclination to abandon the tactics that worked so well for him four years ago: blasts of social media and sprawling stadium rallies. Where a typical president would roll out big jobs and infrastructure plans or a national strategy to combat Covid-19, Trump has deferred to Congress and the states.

Instead he’s embraced an outsider persona, quick to criticize other leaders for failing to halt the pandemic and the unrest stemming from protests against police brutality, while promising to bring change. His vows to reestablish “law and order” echo Richard Nixon’s winning message in 1968. But Nixon’s message worked because he was the challenger, not the incumbent, and wasn’t responsible for the disorder to which voters were responding.

“Part of it is that Trump has never fully embraced the government,” says David Axelrod, a top Obama White House official. “Even as we speak, he’s openly defying the health recommendations his own government is making. He’s at once the leader of the government dealing with the pandemic and also the leader of the response that’s resisting it.”

As unusual as Trump’s style of campaigning has been, Biden’s might be even more so. Some days he’s so absent from the news that it’s hard to believe he’s running at all. His scarcity owes partly to the pandemic, of course. From practically the moment he clinched the Democratic nomination, Biden has been sequestered in the basement of his Delaware home, limited to Zoom chats and phone calls, only recently venturing out to a handful of carefully distanced speaking engagements.

Unlike past White House hopefuls, however, Biden shows little urgency to inject himself into the daily news cycle—a luxury he’s permitted by dint of his broad name recognition, lengthy public record, and strong poll numbers. That’s rare among presidential challengers. When Obama first ran in 2008, Axelrod says, he could never have run a campaign like the one Biden’s running because he needed to introduce himself to voters and convince them he could be president.

But Biden’s eight years as vice president made him a familiar persona—and one who, at least so far, doesn’t polarize voters nearly as much as the last well-known Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton. Although he routinely attacks Trump in interviews and TV ads, he’s just as apt to sound the kind of broad ecumenical themes typical of a sitting president, about the “duty to care for all Americans,” promote racial healing, and lift up “the great American middle class.” In a word cloud of Biden descriptors, “empathy” looms larger than any other, to the satisfaction of Biden’s strategists.

Styling himself an incumbent has been made easier because Trump has shown only intermittent interest in playing a president’s traditional public role. When it comes to state dinners and foreign trips full of pageantry, Trump inhabits it fully; in periods of national crisis, though, he tends to withdraw.

“To the extent that Biden’s intervened in the national dialogue, he’s done so in ways that inject him as decent, conciliatory, and presidential,” Axelrod says, “and he’s assumed that role because Trump has essentially surrendered it.”

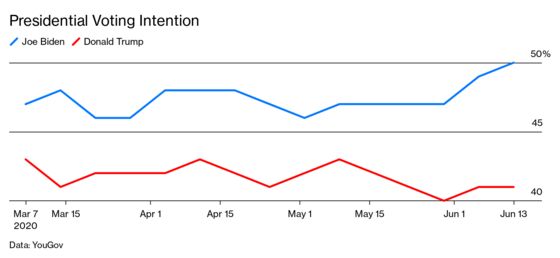

And because he enjoys a wide lead in the polls, Biden has embraced another luxury sometimes available to incumbents, but almost never to challengers: ignoring the press. Biden hasn’t held a news conference since April 2. Meanwhile, the polling disparity has forced Trump’s campaign to push for additional debates, typically a challenger’s ploy to gain momentum.

Running for reelection is never easy. “You start making enemies Day 1 on the job,” Messina says. Yet sitting presidents over the past century usually managed to win because the office carries tremendous power to shape the direction of the country—and with it public sentiment toward its occupant.

Trump has always been more comfortable as an outsider. He ignored political convention four years ago and wound up fine. Maybe he will again. Right now, however, passing up the benefits of incumbency helps explain Trump’s current struggles, just as Biden’s ability to mimic the persona of a familiar incumbent accounts for his steady, and growing, lead.

Read next: Virus Surges Across U.S., Throwing Reopenings Into Disarray

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.