Dig Inn Wants to Optimize Your Sad Desk Lunch

Dig Inn Wants to Optimize Your Sad Desk Lunch

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On any given weekday, millions of office workers descend on downtown streets in search of a decent lunch. At noon on a Tuesday in December, some have found themselves at Dig Inn on East 52nd Street in New York, in line for a healthful-but-hearty grain bowl. Four employees dish out portions of brown rice and Brussels sprouts as several others speed around the open kitchen, replenishing trays of wild salmon and charred chicken. Off to one side, six employees bustle around two banks of steam tables, frantically assembling an endless stream of desk lunches for the growing number of customers who decide not to make the trek. An open laptop displays incoming orders from three different delivery platforms. Every few seconds a digital klaxon announces the arrival of another order, giving the feel of a nuclear power station on the verge of a meltdown.

Scott Landers, Dig Inn’s 27-year-old director of “off-site” (delivery and catering), surveys the scene with barely contained torment as dozens of pink paper bags pile up on an aluminum shelving unit. In 2017, Dig Inn hired Landers, an MIT grad with a background in civil engineering, to rethink the way the company handles delivery—a segment of the industry that has grown faster than many restaurant groups can manage. At this location, it’s not unusual for 60 to 90 minutes to elapse from the time an order is placed to when it’s delivered. “If you look at Yelp scores for delivery vs. guests who come in, it looks like two different brands,” Landers says. Delivery orders score an average of 1.5 stars on Yelp, whereas Dig Inn’s overall rating is a 4.0.

Dig Inn was founded in 2011 by Adam Eskin, a private equity associate turned food entrepreneur, as what he calls a “farm-to-counter” restaurant: food cooked from scratch, sourced directly from regional farms, priced at about $12 a meal. The brand has earned a loyal following for its vegetable-centric fare, expanding to 26 locations in New York and Boston. Seven years after it first opened, the East 52nd Street location relies on delivery orders for 30 percent of its sales. But Eskin concedes that it’s not a very good culinary experience. “Often things are missing, it’s incredibly delayed, it’s not at the right temperature,” he says.

One issue is capacity: Many of the restaurants can’t cook the food as fast as they can sell it. Another is that the cuisine Dig Inn has become known for simply isn’t great for delivery. Guests choose from a selection of three bases—greens or one of two grains—10 sides, and six proteins. “Not even getting into modifications,” Landers says, revealing a series of equations scribbled in a small notebook, “that’s 810 combinations,” so mistakes abound. And then there’s the issue of temperature. Landers inspects one of the outbound meals, a bowl containing farro, broccoli, tofu, and kale Caesar salad, ordered more than an hour earlier. “The hot stuff probably went in at 145 degrees, and the kale Caesar probably went in at 40 degrees,” he says, retrieving a thermometer from his pocket. “It’s now a solidly lukewarm 82—and hasn’t even left the restaurant yet.”

Dig Inn accepts orders directly on its website, but the vast majority come in through third-party platforms, each with its own advantages and limitations. Grubhub Inc. drives about 70 percent of Dig Inn’s delivery business, but its commissions, which can run as high as 20 percent per order for restaurants joining the marketplace, eat into Dig Inn’s profits. As more and more of Dig Inn’s customers have shown they’d rather stay at their desk at lunchtime, Eskin has poured resources into figuring out how to cater to them. “It’s become pretty clear there needs to be significantly more intention than just putting a lid on the food and throwing it in the bag.”

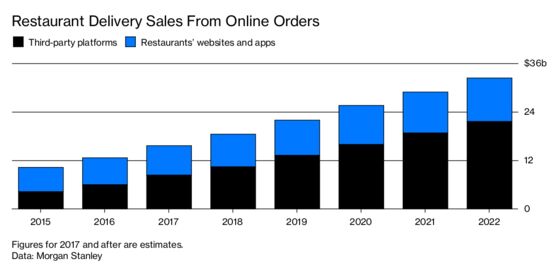

Twenty years ago, when the digital ordering platform SeamlessWeb arrived, the delivery business revolved around pizza; by 2022, according to research by Morgan Stanley, digital delivery may account for more than 10 percent of all U.S. restaurant sales. Demand has grown especially sharply in the past five years, with the arrival of Uber Eats, DoorDash, Caviar, and other services, all competing to transport your lunch for a fee, plus a cut of the restaurant’s profits. In New York and San Francisco, delivery is becoming newly prevalent at lunchtime, allowing office workers to juice an extra few minutes of productivity out of their day. Meanwhile, in cities across the U.S., an explosion of fast-casual chains has disrupted lunch itself. The old-fashioned deli sandwich has given way to endless build-your-own salads and bowls and burritos, ethical burgers, and artisanal pizzas.

Restaurants have greeted the change with a mix of hopefulness and resignation. “When you start out as a restaurant owner, it’s not what you envision,” says Leo Kremer, the co-founder of burrito chain Dos Toros Taqueria, with 20 locations in New York and Chicago. “You envision having the guest experience the service, the design, the playlist, the tables and chairs that you so carefully curated. But there’s this increasingly significant group of guests who want their food delivered, so we’ve been trying to get better at it.” Accepting digital orders boosts sales, but it also means coordinating couriers, soothing unhappy customers, and absorbing third-party fees that can top 30 percent. It’s an arrangement that many in the industry, including Kremer, see as financially unsustainable.

Fast-casual restaurants have been forced to view delivery as a strategic priority rather than an afterthought, especially with a growing number of their diners using marketplaces such as Uber Eats and Grubhub, which accepts more than 400,000 orders on an average day. “When you’re relying on third-party services, you lose your relationship with the customer,” says Lauren Hobbs, the founder of LEH Consulting, which advises hospitality brands on technology.

Instead, restaurants are hoping to funnel customers through their own digital channels. Sweetgreen Inc., the upscale salad and grain-bowl chain, released its own digital order-ahead app in 2016, and now 50 percent of its sales come in this way. The company also uses custom software to help employees assemble orders accurately. When pickup customers found it tricky to add in their dressings in Sweetgreen’s standard bowls without spilling, the company commissioned industrial designers to devise hexagonal ones optimized for deskside mixing. Their kitchens have been rejiggered to include one or more separate production lines dedicated to fulfilling digital orders, a layout that’s becoming the new standard among fast-casual chains including Dos Toros, Cava Group, and Chipotle Mexican Grill. In seating areas, pickup shelving units are edging out tables and chairs.

Many restaurants lack the expertise or investment necessary to build their own digital ordering systems. They turn to software providers that help for a set monthly fee rather than the steep per-order commissions that marketplaces levy. Wingstop Restaurants Inc., Five Guys Enterprises LLC, and other fast-food chains work with a company called Olo to power digital ordering and delivery directly through the restaurants’ websites and apps. Olo now works with 250 restaurant brands, triple the number it served in 2016, with more than 50,000 locations. A rival, Chow Now Inc., offers a similar service geared toward independent operators; it’s in use at 11,000 restaurants in the U.S. and Canada. Noah Glass, Olo’s founder and chief executive officer, says some of his clients woo customers by guaranteeing the best menu pricing on their own platforms, marking up what they sell through third-party marketplaces.

Once customers get in the habit of ordering through a marketplace, it can be challenging to lure them off. But some restaurants are making inroads. Luke’s Lobster LLC, a seafood chain with 39 locations in the U.S., Japan, and Taiwan, introduced its own app in 2018 and has converted about a quarter of its digital orders to that channel by offering a loyalty program and referral credits. Bareburger Group LLC, a sustainability-focused burger chain, has seen similar results by running promotions available only on its app and mobile website; it intends to sever ties with ordering marketplaces by 2020. When Dig Inn starts its revamped delivery offering, called Room Service, at the end of January, the company wants to tempt its diners away from Grubhub with an even larger draw: a new menu optimized for delivery, available exclusively through the Dig Inn website and app.

For the past 18 months, while Landers has worked to build Dig Inn a better delivery machine, the company’s chief culinary officer, Matt Weingarten, has been developing a new menu that’s specifically designed to travel. Up until now, Weingarten says, delivery has been a simple race against the clock, with food quality gradually degrading as time passes. “Now we’re figuring out how we make it improve over time. How do you set the temperatures and textures so that they’re good now but actually better in 20 or 30 minutes?” In mid-2017 he hired a young chef named Gabriel Dilone to experiment with these questions full time. Dilone has been working from three new subterranean delivery kitchens across Manhattan, from which the company will eventually be able to reach much of the borough.

Dig Inn isn’t the first company to deal with the toll that delivery takes on dishes that were designed to be eaten immediately. Ando, David Chang’s now-shuttered delivery-only restaurant, and Maple, a failed delivery kitchen in which Chang was an investor, were both developed with transit in mind. They drew praise for their food, but struggled with the economics of a delivery-only business. Zume Pizza Inc., an automated pizza-delivery company in Mountain View, Calif., has delivery trucks that can cook pies en route to their destination. But the vast majority of restaurants simply bag up what they sell in-house. Weingarten and Dilone say they’re hoping that a little kitchen science can substantially improve on what customers have come to expect from delivery.

All Room Service offerings have been designed so that hot and cold items are packaged separately, to avoid an unpleasant room temperature mix. At Dig Inn’s Midtown delivery kitchen, Weingarten showed me a salade niçoise with rosy slices of tuna loin, vibrant green beans, and a six-minute egg, and a heartier option of roasted mushrooms, turnips, walnuts, frisee, and duck confit. Warm entrees are designed to arrive hot but not overcooked, and many were conceived to finish cooking as they travel. Dilone roasts a wild king salmon fillet in a CVap—a controlled vapor technology oven that steam-roasts food, helping keep it moist—just until it hits 105F before placing it on top of screaming-hot fennel-potato puree. By the time the dish has sat around for 5 to 10 minutes, then traveled 5 or 10 minutes in a delivery bag, the puree transfers its heat into the fish, cooking it to a perfect 125F.

Kale polenta and sunflower risotto are sent for delivery while still “loose”; starches thicken as they cool on the way to the customer. Rather than offering steak—which should be served pink in the middle but would overcook as it travels—Dilone and Weingarten are experimenting with braised chuck roll, a fork-tender hunk of beef that holds heat well. “Focusing on confits and braises lets us get a more even cook all the way through, so that you don’t have to worry about it changing in weird ways,” Weingarten says.

Gone from the delivery menu are Dig Inn’s customizable bowls with 810 iterations in favor of a rotating selection of six to eight entrees, plus sides, snacks, and drinks. Entrees will be priced between $15 and $20, including the cost of delivery. Weingarten believes this will cut down substantially on both inaccuracies and the time it takes to fulfill orders. With a proprietary predictive algorithm that uses sales history to estimate demand for each dish, the kitchen crew can stay a few minutes ahead of orders as they come in. Rather than employing its own fleet of couriers, Dig Inn will work with the logistics company Relay Delivery Inc.—in testing, their couriers retrieved an order within an average of three minutes. The size of each delivery zone has been limited so travel times don’t exceed 15 minutes. All told, Dig Inn expects the new system to shave delivery times down to 30 minutes or less.

When Room Service starts, it will be available only through the Dig Inn app and website; this strategy is intended to decrease and eventually eliminate the company’s reliance on third-party marketplaces. Dig Inn is starting slow: Initially Room Service will be available from only one kitchen, in downtown Manhattan, and only for dinner—a time of day when the company is hoping to bump up sales. Eventually the new hubs will all be open for lunch, and Dig Inn will phase out its legacy delivery operations altogether.

In a basement kitchen near Times Square, a staff of five is going through a mock service run, simulating how the space flows at full speed. The operation hums along quietly, with orders coming in as fast as they do on East 52nd Street. Landers whisks salades niçoises and bowls of lamb couscous into bags within seconds of an order hitting the dashboard. Eskin says the Room Service kitchens will turn out as many as four orders per minute at peak times, but he doesn’t know whether that will be enough to meet demand. “We’re realizing now, with these hub kitchens that we’ve built, it’s already obvious that we’ve built them way too small,” he says.

After I left, I texted Eskin, asking whether, like Dos Toros’s Kremer, he worries about making delivery too appealing, hastening a future in which meals lose their social aspect entirely and we all have fewer reasons to look up from our desk. “If it were possible for consumer behavior to evolve in reverse, whereby more and more folks were coming in to the restaurant for an experience and less and less were ordering delivery, we’d all be better off for it (humans, restaurant businesses—all),” Eskin replied in a text message. But the world is changing around Dig Inn, and the choices are to evolve with it or sit back and watch while some other restaurant eats your lunch.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Silvia Killingsworth at skillingswo2@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.