Despite Trump’s Claims, There’s No Currency War Against the U.S.

Despite Trump’s Claims, There’s No Currency War Against the U.S.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s usually not hard to tell when a war has started: One nation crosses another’s border with soldiers, tanks, and planes. Currency wars are tougher to call, partly because there isn’t even a clear definition of what they are. Keep that in mind when evaluating President Trump’s accusations against central banks in Europe and Asia, such as this June 18 tweet: “Mario Draghi just announced more stimulus could come, which immediately dropped the Euro against the Dollar, making it unfairly easier for them to compete against the USA. They have been getting away with this for years, along with China and others.”

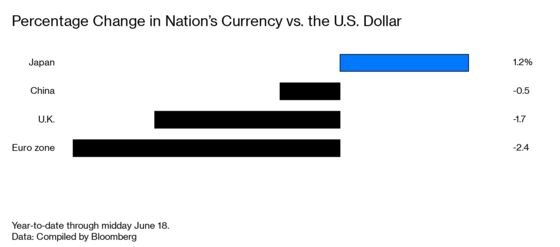

Trump is right on two scores. The euro really did decline against the dollar, to $1.12 from $1.16 a year ago, after Draghi, the outgoing president of the European Central Bank, said “additional stimulus will be required” if the economic outlook for the 19-country euro zone doesn’t improve. Trump is also correct that a cheaper currency would likely boost the region’s economy by making exports from the euro zone cheaper abroad, and by making imports from the U.S. and elsewhere more expensive.

But many economists disagree with Trump that Draghi is doing something wrong. It would be legitimate for the ECB to cut interest rates, they argue, to stimulate domestic economic growth by lowering borrowing costs for consumers and businesses. Of course, cutting rates would likely reduce the value of the euro, which adds to the stimulus, but that’s a side effect, not the goal. “We don’t target the exchange rate,” Draghi said during a June 18 panel discussion in Sintra, Portugal.

Let’s say the depreciation of the euro managed to worsen the U.S. trade deficit enough to slow down the American economy. The Federal Reserve could respond by cutting interest rates to rev growth. That would incidentally lower the value of the dollar, returning it to its previous exchange rate with the euro. But as in the case of the euro, a weaker greenback would be a side effect of the lower rates, not a primary goal.

It might look like a zero-sum stalemate when two trading partners both cut interest rates, leaving the exchange rate where it started. But it’s not. It’s an overall loosening of monetary policy, which is good for growth in both countries, says Brad Setser, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. “In principle,” he says, “that’s just a coordinated easing that increases the level of demand.”

Trump’s argument that China is manipulating its currency is even weaker than his case against Europe. Far from pushing down the value of the yuan, the People’s Bank of China has been countering market forces toslow its decline. China has kept the benchmark one-year lending rate at 4.35%, where it’s been since October 2015, in spite of economic softness that might seem to justify a cut. Also, China’s holdings of foreign reserves haven’t risen appreciably, as they would if China were trying to drive down the yuan by selling it and buying other currencies. “The available evidence suggests that China is trying to avoid a currency war,” Setser says.

Chinese leaders don’t want a weaker currency, even if it gives a short-run economic boost, says Marc Chandler, chief market strategist at Bannockburn Global Forex LLC in New York. The country’s long-run objectives are “to move up the value-added chain” and encourage the Chinese “to work smarter, not harder,” Chandler wrote in a June 18 note to clients. Competing on price through a cheap yuan would keep China stuck in its low-tech past.

How would anyone know if a country really were playing unfair by depreciating its currency? One telltale sign is the central bank buying lots of foreign currency to reduce its own currency’s value, even though the country has a big surplus in trade and investment income with the rest of the world. China was guilty of that behavior up until early 2014. Singapore, South Korea, and Thailand have also intervened at various times in recent years to suppress their currencies’ value.

Today one of the chief currency offenders is Taiwan, Setser wrote in a June 18 research note. The Taiwanese central bank says it had $464 billion in foreign exchange at the end of May. That’s more than the holdings of bigger nations such as Brazil, Germany, and India. (According to a description on the central bank’s website, the value of the Taiwan dollar is determined by forces of supply and demand, though “when the market is disrupted by seasonal or irregular factors, the Bank will step in.”)

It seems, then, that Trump may be pointing his finger in the wrong direction. But since the president seems to have an expansive view of what constitutes unfair trading practices, the tweets against Europe, China, and others are likely to continue.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.