Desperate Airlines Turn to European Governments for Support

Desperate Airlines Turn to European Governments for Support

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Early in March, aviation executives convened in Brussels to discuss the state of their industry. The new coronavirus was raging in Asia, crushing travel demand, but Europe looked set to dodge a major hit, or so believed the participants in the conference.

Bookings would likely return to normal in a few weeks, and “people will get bored of the coverage” of the virus, Ryanair Chief Executive Officer Michael O’Leary predicted. Besides, airlines shouldn’t use the outbreak as an excuse to seek government aid and prop up failing businesses. “Keep calm, give people rational advice, and then let the bankrupt go bankrupt, because that what’s going to happen—whether it’s before, during, or after Covid-19,” O’Leary said.

Less than a month later, the global aviation industry is trying to hold on to a business facing annihilation from the virus, which is now wreaking havoc in Europe, the new epicenter of the pandemic.

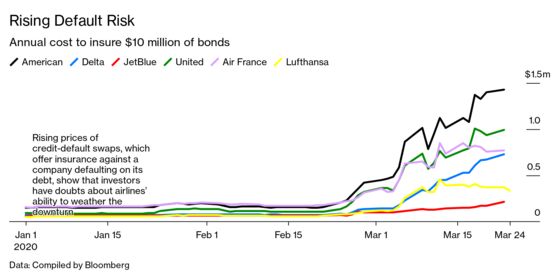

Airlines across the globe face $252 billion in lost revenue this year, the International Air Transport Association, which represents 290 airlines, warned, calling the crisis more severe than anything the sector has ever faced. The outbreak will reshape the industry, with many airlines failing, others consolidating, and entirely new alliances emerging, the group predicts.

Governments have long held their protective hands over airlines, in part out of national pride, in part to secure jobs. Germany alone has more than 100,000 people working in the aviation sector, the majority at private companies such as Deutsche Lufthansa AG or the major airport operators. As a result, flag carriers have rarely gone under, with a few exceptions such as Malev in Hungary, Sabena in Belgium, and Swissair, which collapsed in 2001 only to be reborn as SWISS and folded into the Lufthansa group.

As the coronavirus has scared away travelers, airlines from Lufthansa to Norwegian Air Shuttle ASA have asked for government assistance after grounding their fleets on an unprecedented scale. Even British Airways, which had initially belittled calls for U.K. assistance by smaller rival Virgin Atlantic Airways Ltd., is lobbying for government help.

The carriers’ implicit message to their home governments: Engineer bailouts or prepare to see some local champions grounded for good. That’s put governments in the challenging position of trying to pick deserving recipients for state funding. The response so far has shown little coordination across the region. Italy, the hardest-hit country, with more than 6,000 Covid-19 fatalities, pledged €600 million ($647 million) to nationalize Alitalia. Norwegian Air Shuttle secured government funding worth as much as $270 million to keep it going, though with many strings attached. Finland pledged €600 million of guarantees to prop up Finnair, of which the state owns almost 56%, while Stockholm-based SAS AB will get a total 3 billion Swedish kronor ($300 million) in state guarantees from Sweden and Denmark. “With airlines having to ground fleets, they’re still liable for lease rentals and other fixed costs, and without state support, they will fast go out of business,” says Mark Martin, an aviation consultant based in Delhi.

Not every carrier has been met with open purse strings. Flybe, Britain’s largest domestic airline, failed on March 5 after the U.K. earlier this year decided not to defer its massive tax bill even as it struggled with a virus-caused traffic plunge. A jet fuel supplier cut it off, and creditors began seizing its planes.

Europe has been no stranger to struggling airlines. Some went bust in recent years, such as Air Berlin and Monarch in the U.K., while others muddled through under government supervision, including the perennially unprofitable Alitalia. Still others limped along, like Norwegian Air, the discount specialist. “Throwing liquidity at crippled airlines and members of the supply chain isn’t the best answer—far from it,” says Sandy Morris, an aviation analyst at Jefferies in London. Instead, governments should help alleviate cost burdens like leasing rates by buying aircraft, he says.

The U.K. government made clear that it sees state-led bailouts only as the last resort once all other options, such as raising funds from existing shareholders, have run dry. “Further taxpayer support would only be possible if all commercial avenues have been fully explored,” Chancellor Rishi Sunak wrote in a letter to aviation executives.

Yet the region’s authorities seem determined to throw the industry a lifeline. European Union competition authorities have lifted a ban on extra aid for companies that got rescue funding in the past decade. Regulators also suspended an obligation for carriers to use 80% of their takeoff and landing positions or risk losing them the following year.

“Governments will do whatever it takes to keep things going in aviation, but like with the banking industry in and after 2008, there will be long-term ramifications,” says Robert Stallard, an analyst with Vertical Research. “Who knows exactly what the details will be, but nationalized airlines wouldn’t surprise me.”

The government intervention risks undoing decades of privatization in the European aviation industry. British Airways, sold by the government in 1987, was among a host of state-owned entities, from utilities to manufacturers, that were privatized during the Margaret Thatcher era.

Lufthansa, which the German government began privatizing in 1994, also includes formerly state-owned SWISS and Austrian Air, which left government hands in 2006 and 2010, respectively.

Airbus SE, a huge pan-European manufacturing success story, fought a long battle to rid itself of what it considered burdensome government intervention, which once dictated everything from how resources were allocated to which executives were promoted. France and Germany each hold about 11% of Airbus’s stock, and the Spanish state owns about 4%, though the countries don’t hold direct sway via board representation.

European politicians have generally avoided the belligerent tone that’s emerged in Washington over economic rescue packages, in which Democrats held up aid legislation trying to attach conditions such as prohibiting stock buybacks and limiting executive pay. Some safeguards are already baked into the continent’s system, such as strong labor unions and state-sponsored salary subsidies that help alleviate the burden on temporarily laid-off workers.

“There’s no free lunch when it comes to government intervention,” says Mark Manduca, an analyst at Citigroup in London. Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury emphasized that airlines and suppliers should be the first recipients of government aid, and that his company can stem the crisis on its own for now after scrapping its dividend and securing credit lines to create a €30 billion safety net. Most European airlines’ finances aren’t that strong. Whatever support governments provide, says Sash Tusa, an analyst at Agency Partners in London, “will be imperfect, and it will be survival of the fittest.” —With Siddharth Philip and Charlotte Ryan

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.