Democrats Pin Their Midterm Hopes on Registering New Voters

Democrats Pin Their Midterm Hopes on Registering New Voters

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Five years ago, when Stacey Abrams was Democratic minority leader of the Georgia House of Representatives, she created an organization called the New Georgia Project with an eye on a beguiling set of figures. The first was 1.5 million, the number of people who’d moved to the state since 2005. The second was 20 percent, the proportion of those migrants who were white. And the third: 700,000, the estimate of how many minority Georgians weren’t registered to vote.

Now Abrams is trying to become the first black woman governor in U.S. history. Her chances will depend in large part on how those numbers manifest themselves on Nov. 6. Abrams has been preaching the demographics-as-Democratic-destiny doctrine for years. She’s spearheaded minority voter registration drives in Georgia and become an advocate for expanding voter rolls and ballot access nationwide in a way that would bolster her party.

That destiny assumes, though, that the new electorate votes, enabling Democrats to deliver unprecedented midterm turnout despite what they say are Republican efforts to suppress Democrat-leaning voters. Five years after Abrams formed the New Georgia Project to register minorities, the drive has yet to move the needle on any statewide race. The shift that was going to erode Republican dominance in the state has yet to materialize.

Some Democrats wonder whether this year will be any different. “There’s a very, very good chance that demographic, policy, and political elements are going to converge someday, and they may well converge this November,” says Vincent Fort, a former state senator and member of the legislative black caucus. “But I have cautioned my Democratic brethren not to depend on demographics too much.”

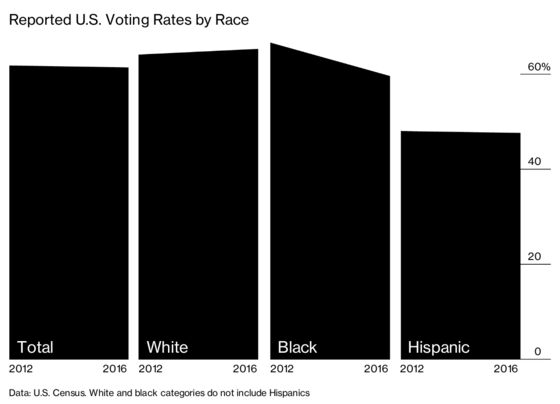

Lagging minority turnout contributed to Hillary Clinton losing the presidency. Nationally, the rate of black voter turnout in 2016 declined for the first time in 20 years during a presidential cycle, dropping 7 percentage points from a high of 67 percent in 2012, according to the Pew Research Center. More than 765,000 fewer black voters cast votes in 2016 than did to elect Barack Obama to a second term. And an expected surge in Latino voters fell short.

The apathy cost Clinton in states such as Michigan and Wisconsin, both of which turned red. In Wisconsin, Trump got about the same number of votes Mitt Romney did in 2012, whereas Clinton fell 200,000 short of Obama’s votes four years earlier. Turnout next month will be critical to whether Republican Governor Scott Walker wins a third term or Democrat Tammy Baldwin keeps her U.S. Senate seat.

In the South, a revved-up pool of minority voters could buoy Democrat Beto O’Rourke in his bid to unseat Texas Senator Ted Cruz, help Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum beat Trump-endorsed Republican Ron DeSantis for governor, as well as aid Abrams in Georgia. She’s running against Republican Secretary of State Brian Kemp, who has a Trump endorsement. Although Florida is a swing state, Georgia and Texas have been reliably red for years. The latest polls rank Florida and Georgia as toss-ups, with Gillum slightly ahead and Abrams slightly behind their Republican rivals. Cruz is considered a likely win.

In Texas and Georgia, Democrats have been saying since 2014 that the flipping point had arrived—a promise that political scientists have questioned and the electorate has consistently broken. In Georgia, Democrats have put forward one explanation: voter suppression. The New Georgia Project says it’s submitted 225,000 voter registration applications to the state since 2014. That’s close to the 250,000- to 300,000-vote margin by which Republicans win statewide races. But the project can’t say how many of those voters were added to the rolls.

As the secretary of state, Kemp has aggressively culled the rolls of people who neglected to vote, including 668,691 in 2017 alone. He also rejected or delayed voter registration applications if names or addresses didn’t exactly match other public records, down to missing hyphens. Kemp agreed to halt the match requirement in a legal settlement with the NAACP and other voting access advocates in February 2017, but he started it again after the Republican state legislature passed a law requiring it a few months later. On Oct. 12, civil rights groups sued the state over 53,000 voter registrations that haven’t been added to the rolls this year because of the exact-match requirement.

Abrams made a name for herself in 2014 when she said New Georgia would register 120,000 minority voters that year. The organization ended up submitting applications for three-quarters of that number, of which only 46,000 were officially registered in time for the midterm election. In a messy fight with Kemp, Abrams and others accused him of suppressing the vote. Kemp, in turn, accused New Georgia of voter fraud and started a criminal investigation. No one was charged.

Through a wider lens, the promise of a demographics-driven shift toward Democrats was a reach in 2014 and 2016, according to Andra Gillespie, a political scientist at Emory University in Atlanta. Population shifts have changed politics locally but haven’t had the same impact statewide because the new voters Democrats are counting on are young, she says. Registered voters don’t become reliable voters until they’re closer to middle age, she says, so Democrats will have to be patient.

Still, the party has seen some encouraging numbers this year. Democratic turnout for the May primaries was 555,000, up 40 percent from 2010, the last time the state had a competitive governor’s race. Democratic primary turnout still lagged Republican turnout, but by only 52,000—far less than the nearly 300,000-vote margin in the previous two gubernatorial primaries. The early voting that began Oct. 15—typically a boon for Democrats—had three times as many voters on its first day as in 2014. If those trends repeat on Nov. 6, Abrams might make history.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Dimitra Kessenides at dkessenides1@bloomberg.net, Flynn McRoberts

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.