Taxing the Ultra-Wealthy Forces Democrats to Get Creative

Taxing the Ultra-Wealthy Forces Democrats to Get Creative

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Democrats these days are throwing around plans for new and unprecedented taxes on wealth, financial transactions, capital gains, and inheritances. Tantalizing them are the trillions of dollars of wealth in the hands of the richest 0.1%, much of it escaping taxation.

Republicans passed their own tax-reform bill less than a year after President Trump took office, giving substantial breaks to the rich. While a Democratic version in 2021 would require taking back both the White House and U.S. Senate, almost every Democratic presidential candidate says higher taxes on the wealthy are a priority. Squeeze the billionaires, their thinking goes, and the next president can not only fund progressive priorities but also start to reverse a decades-long trend of widening inequality. That’s far easier to put into a tweet than into the tax code—merely hiking income tax rates might not bring in much revenue, especially from the top 0.1%. To really get more from the rich, creativity will be required.

In white papers, books, and conference rooms, progressive tax experts are questioning basic assumptions about how the tax system works. “What is surprising is the pace at which the debate is changing,” says Jonathan Traub, managing principal of Deloitte Tax LLP’s national tax practice in Washington. “It is a theoretical rethinking of our bases of tax.”

If Democrats take power next year, they could of course just raise income tax rates on the rich. In an interview in January, New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez suggested putting a 70% top rate on income over $10 million. Without changing other aspects of the tax code, though, higher rates will neither hit most of the top 0.1% nor raise much revenue, according to an influential paper released by Lily Batchelder and David Kamin, former advisers to the Obama administration who are now law professors at New York University. A 70% top rate would raise only $260 billion to $320 billion over a decade, they estimate.

If you’re overhauling the Internal Revenue Code, Batchelder and Kamin argue, you can pull in more money—trillions of dollars, not billions—if you target the many ways the very rich avoid taxes altogether: The estate tax is full of gaping loopholes; multinational corporations owned by billionaires skip corporate levies by moving profits to offshore havens; and the IRS, starved for resources, struggles to keep up with the top 0.1%’s legal and illegal tax dodges.

The wealthiest business owners and chief executive officers have one especially versatile tool: They control when, and in what form, they receive income. That’s where a new approach to capital-gains taxes from Oregon Senator Ron Wyden, in line to chair the Senate Finance Committee if Democrats win back the chamber, comes in. “My proposal is simple,” he says. “It would treat income from wealth like income from wages.”

Right now, income is only taxed when it’s realized—when, for example, a person receives a paycheck, sells a stock or piece of property, or gets a dividend. The richer you are, the more flexibility you have on when to sell and trigger a tax bill or a tax loss. The wealthy can borrow against investments rather than sell assets and pay taxes. Billions of dollars in capital gains can get deferred for decades or, if held until death, forever. According to a few recent studies, the top 0.1% end up reporting to the IRS just half, or even less, of their total earnings.

Wyden’s plan would raise today’s lower rates on capital gains while forcing the superwealthy—those with at least $10 million in assets or $1 million in annual income for three years—to pay taxes on their gains every year, whether they were realized or not. In this “mark-to-market” system, the rich would report all gains and losses on stocks and other publicly traded assets to the IRS every year. Gains become taxable income, while losses can be deducted. For private assets, the rich would pay an extra tax when they realize gains, based on a formula that shrinks the benefit they receive by deferring the sale.

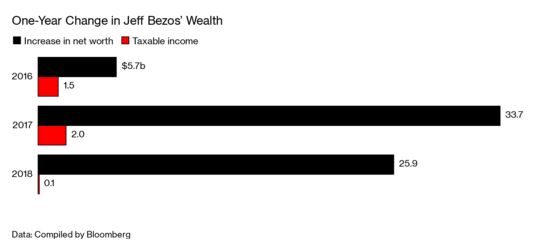

The 10 wealthiest Americans got $163 billion richer over the past three years, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. But it’s likely they paid taxes on less than a quarter of those gains. Jeff Bezos’ net worth jumped $65 billion from the beginning of 2016 to the end of 2018, making him the richest man in the world. But a Bloomberg analysis estimates he received only $3.5 billion, or about 5% of his gains, as taxable income. Warren Buffett got $21.5 billion richer in the past three years, while selling only $13 million in Berkshire Hathaway Inc. stock—less than 0.1% of his paper gains.

Another way to tax built-up wealth, which former Vice President Joe Biden and many other Democrats support, would be to repeal the provision that wipes out the taxable capital gains on assets passed to children and grandchildren after death. Then there’s the estate tax, which has become increasingly easy to avoid. Batchelder has suggested revamping what critics call the “death tax” into a more politically palatable “inheritance tax” that’s technically paid by heirs rather than the estate. Bernie Sanders has floated the idea of hiking rates on billionaires’ estates from 40% to 77%.

What about a direct wealth tax, as both Sanders and Elizabeth Warren propose? Roughly speaking, a wealth tax works like this: You calculate a household’s net worth, then charge an annual levy on the amount above a certain level. In Warren’s plan, households would pay 2% on net worth of $50 million to $1 billion. Above $1 billion, they’d pay 6%.

A wealth tax is popular with voters, but it wouldn’t be easy to implement. Many conservatives say it’s unconstitutional, and the IRS would face an administrative headache valuing the fortunes of tens of thousands of rich families every year. “At the end of the day, people don’t think this is going to get passed,” says Eric Hananel, a principal at UHY Advisors in New York who consults for high-net-worth clients. Wyden’s mark-to-market capital-gains tax could be just as complicated to put into law. For one thing, as markets fluctuate, the IRS could end up collecting huge sums from billionaires one year, only to hand them back the next in the form of deductions for investment losses.

These potential swings are a problem for University of California at Berkeley’s Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, advocates of the wealth tax and advisers to Warren and Sanders. The economists argue that a mark-to-market tax could fall heavily on entrepreneurs in high-risk, high-return ventures while leaving wealthy people with more conservative investments relatively untouched.

To survive constitutional scrutiny, scholars say, a wealth tax might be redesigned to look more like a tax on income. Or perhaps aspects of the mark-to-market and wealth taxes could be combined to make them work better. For both the wealthy and the U.S. Treasury, the “details are really going to matter,” says Deloitte’s Traub. A future Democratic Congress could in the end pursue “much less sexy, incremental” changes, says University of Chicago finance professor Eric Zwick. A better-designed and higher corporate tax, for example, could take cash from billionaire shareholders that they aren’t paying on their individual returns. “There’s a lot of room to improve existing taxes,” Zwick says. “But it doesn’t look as good on a bumper sticker, so I’m not surprised that politicians aren’t jumping on that.” —With Tom Maloney

Read more: Democrats Cool on Wall Street Donors, and the Feeling Is Mutual

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.