When Same-Day Delivery Is Too Slow

When Same-Day Delivery Is Too Slow

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- To customers dropping in for a quick bottle of pinot grigio, the BevMo! on Junipero Serra Boulevard in Colma, a few miles from San Francisco State University’s campus, looks like one of the chain’s standard outlets—same red signage, same rows of bottled booze. But tucked away in a 2,000-square-foot storage room outside of public view is a new addition, a so-called dark convenience store stocked with items appealing to the most urgent needs of the surrounding population. There are sex pillows, vibrators, whips, and emergency contraception, along with fake eyelashes, frozen food, and printer paper. Couriers wait in parked cars outside, ready to spring into action in case a customer has a sudden need to prepare for an intimate encounter or a day of working from home.

The back room is the work of Gopuff, a Philadelphia-based delivery startup that’s raised $3.4 billion from investors including SoftBank Group Corp.’s Vision Fund at valuations as high as $15 billion. The startup aims to provide customers with a wider and more eclectic range of products than they’d find in a convenience store, delivered to their home within a half-hour of placing an order through an app. It bought BevMo for $350 million late last year to gain a foothold in California.

Since then, Gopuff has bought a chain of liquor stores in Kentucky, a pair of European delivery companies, and a fleet-management and mapping software company. Gopuff serves about 1,000 cities from more than 550 locations globally, and it’s opening an average of one or two more a day, fueled largely by pandemic-era enthusiasm for commerce that doesn’t involve leaving the house. Growth that fast comes with issues, though: The company has to quickly identify the best places for its warehouses, anticipate what items to stock to meet local demand, keep perishable items from going bad, and staff its delivery operations in the most competitive labor market in recent memory.

The promise of leveraging the web to enable near-instant delivery has captured the imagination of entrepreneurs since at least the first internet bubble, when startups Kozmo and Urbanfetch offered delivery at speeds and prices that seemed almost too good to be true—then famously collapsed under the weight of unsustainable business models. More recently, DoorDash, Instacart, Uber-owned Postmates, and others have focused on food delivery, avoiding the costly infrastructure requirements their predecessors had by using independent couriers to deliver products from existing restaurants or stores.

Gopuff’s plan is old-fashioned compared with those of the DoorDashes of the world. It buys inventory at wholesale prices, stocks it in locations convenient to dense populations of potential customers, and then charges retail prices plus a delivery fee of $2 or so. It’s a simple concept that’s tricky to execute, according to Ryan Sweeney, a partner at venture capital firm Accel who’s been backing Gopuff since 2018. “The mini-warehouse model is very unique and hard to do,” he says. “This is not just another delivery play.”

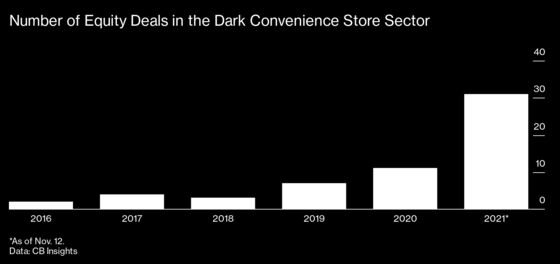

In the first nine months of 2021 venture investors poured $5.8 billion into the dark convenience store sector, compared with $496 million in 2020 and $1.1 billion in 2019, according to research firm CB Insights. Flink, Getir, Gorillas, and Buyk, and other companies are all executing similar strategies. On Dec 2., rapid delivery firm Jokr said it had raised $260 million from investors who valued the company at $1.2 billion. DoorDash and Uber Eats are competing for customers by expanding to offer deliveries from pharmacies and grocery stores.

Despite the enthusiasm from investors, there’s no consensus that the basic business model even works, according to Laura Kennedy, a lead analyst with CB Insights. “You do have to question whether they can all survive,” she says. “We’ve gone past the delight of having things delivered to your house.” A Gopuff spokeswoman says the company was profitable in its early days but is now focused on investing in expansion. She declined to say when the company expects to be profitable again.

Gopuff initially set out to solve the late-night needs of students at Drexel University in Philadelphia. Its co-founders, Rafael Ilishayev and Yakir Gola, were students there, sons of immigrants who worked in their families’ businesses growing up. They hired a programmer to build a mobile app, and bought snacks, booze, condoms, and smoking paraphernalia in bulk. Starting in 2013, the two men began personally shuttling items to nearby dorm rooms and apartments. Depending on who you ask, the pair named the company after either Drexel’s dragon mascot or the company’s focus on smoking products. When pressed about the name’s meaning now, some employees just laugh and roll their eyes.

Gopuff saw itself as providing not only convenience but also discretion for deliveries that might be sensitive or embarrassing. “Judgment is a big thing. Otherwise we wouldn’t be selling so many Plan Bs,” Ilishayev told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 2017, referring to the emergency contraceptive.

As Gopuff expanded to a handful of East Coast markets, it saw the chance to distinguish itself by collecting and analyzing customer data to make better business decisions—perhaps an ironic focus for a company whose pitch was keeping people’s personal taste in hookahs to itself. It used this information to decide which items to stock—at-home Covid-19 tests, cleaning supplies, and baby products have surged over the past year—and where to locate facilities, as well as to power its growing targeted-advertising business. “The name of the game is collecting as much information as we can,” says Gopuff’s head of business, Dan Folkman.

The BevMo purchase gave Gopuff 161 retail stores, along with the food and beverage licenses to operate them. Gopuff has added about 100 delivery facilities to BevMo stores so far. Last year, the company also began preparing hot food and drinks in small kitchens built mostly in existing locations or their parking lots; it has more than 60 operating.

There’s evidence Gopuff has sometimes had trouble managing its expansion pace. Food spoilage has been a problem since at least 2017, with employees regularly throwing away hundreds of cases of ice cream because of poorly timed deliveries or spotty refrigeration, and two former employees cited frequent rodent infestations. “There were always mouse issues and poop to clean up,” says Nicholas Fernandes, one of the ex-employees, who packed deliveries in a Boston warehouse until late 2018.

Logistics problems persisted as recently as this spring, often because there was no room inside warehouses to walk between aisles, according to Bill McNeely, who handled driver operations at 54 sites in Texas before leaving the company for another job. “Stuff would show up two to three times a week, and there wasn’t any room for it,” he says. “It was chaos.”

The Gopuff spokeswoman describes food waste as an “unfortunate but at times inevitable” issue across food-related industries, but says the company’s spoilage rates are below industry averages, without providing specific data. She says the company prioritizes health and safety, and conducts regular audits, inspections, and training.

Delivery companies relying on gig workers have been brutal about offloading financial risk onto the workers themselves, by hiring them per delivery instead of for a shift. Gopuff pays its drivers for set blocks of time regardless of whether there are deliveries, to ensure it has enough couriers ready at an instant. This approach isn’t always cost-effective, especially in new markets. On a recent afternoon at a BevMo location in Oakland, a batch of Gopuff drivers were napping in their cars or scrolling through TikTok in the parking lot and nearby streets. “You get paid for just sitting here,” said Mitzi Lewis, a 54-year-old grandmother who’s been working for Gopuff since this summer. “It’s good.”

Gopuff’s ability to manage its inventory and labor force are the key factors in whether it will make its business work at its rapidly increasing scale. The company has little choice but to keep expanding, given how many competitors are trying to gain a foothold in choice markets. Berlin-based Gorillas, valued at $2.1 billion and backed by Delivery Hero, DST Global, and others, and Istanbul-based Getir, valued at $7.5 billion and backed by Sequoia Capital and Tiger Global Management, both began operating in the U.S. this fall. While Gopuff boasts it has sliced delivery time from 30 minutes to 20, Gorillas and Getir say they can cut that time down to just 10.

Read next: The People and Ideas That Defined Global Business in 2021

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.