Cross-Country Skiing’s Dirty Little Fluorinated Secret

Cross-Country Skiing’s Dirty Little Fluorinated Secret

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- I became a real cross-country skier a decade ago, on the eve of a big race. I stood before the register at my local ski shop, coveting a matchbook-size, yellow sliver of ski wax priced at $5 a gram, feeling my pulse race, my fingers quavering as I thrilled over the glory and speed this little wafer of magic could bring once I ironed it into the base of my skis. I laid down a hundred bucks for that wax, and I’m almost certain I covered 50 kilometers a few minutes faster thanks to it. How could I not have? Fluorinated ski wax is so eerily effective that, in describing it, fellow skiers at times drift toward the rhetoric of religion. “It’s the most joyous thing I’ve ever experienced,” Andrew Gardner, until recently the head coach of Nordic skiing at Middlebury College, says of gliding on fluorinated boards. “It’s so completely unnatural.”

The fastest fluoro wax contains a synthetic fluorine-based compound—perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, which boasts eight fully fluorinated carbon molecules in its long backbone. The compound’s star is fluorine. This element forms a tighter chemical bond with carbon than any other, and it creates, essentially, a shield against the ski-slowing moisture that pervades snow most thoroughly when temperatures approach or rise above 32F. Once bonded with carbon, fluorine is exquisitely unreactive; it scarcely sticks to anything. That’s why PFOAs are a key ingredient in Teflon. When firefighters spray foam laced with PFOAs onto a blaze, it has a suffocating effect.

As you might have guessed, PFOAs are bad for the environment. Numerous studies have noted contaminated drinking water near airports because of the PFOA-laced firefighting foam used to put out airplane fires. And in 2010, after Sweden’s Vasaloppet, the world’s biggest Nordic ski contest, with 30,000 entrants, scientists tested the snow and soil and found them tainted with fluorocarbons, which have been linked to cancer, liver damage, birth defects, hypertension, and strokes.

In July 2020 the European Chemicals Agency will ban the sale, manufacture, and import of all products containing PFOAs. Slightly less toxic and less miraculous to skiers, with a backbone containing just six fully fluorinated carbon molecules, C6 fluorocarbon seems poised to become illegal in Europe in 2022. Meanwhile, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is investigating numerous U.S. wax purveyors, including Swix Sport USA, whose Norwegian parent company, Swix Inc., makes about 60% of all fluoro ski wax worldwide.

Swix Sports USA denied a request to discuss the EPA’s investigation; the EPA said in an emailed statement that certain waxes are in violation of the Toxic Substances Control Act. The agency wouldn’t comment on why some fluoro ski waxes are still being sold in shops and online. “As a matter of policy,” it said, “the agency is unable to discuss compliance monitoring.”

Speculation abounds among skiers that it’s just a matter of time before the EPA outlaws fluoro wax. Since 2009, Swix has been trying to find a more environmentally friendly wax that’s as fast as fluoro. Fast Wax, based in Watertown, Minn., is experimenting, too, and it plans to stop jostling for fluoro wax market share. “Why fight for deck chairs on the Titanic?” says owner Casey Kirt.

In fact, fluoro wax, which made its debut in the late ’80s, has never really been a big moneymaker. It isn’t wildly popular with the downhill skiing masses (over a quick three-minute schuss, its benefits are scant), and it accounts for only about $50 million in annual sales worldwide. Still, fluoro has long cast a troubling haze over the few thousand cold-tolerant ectomorphs who huddle at the core of the Nordic ski universe.

Patrick Weaver, the Nordic coach at the University of Vermont, says that whenever he waxes with fluoro, he dons rubber gloves and wears a $1,200 vacuum-pack face shield replete with toxin-mitigating fans. “The stuff isn’t good for our bodies,” Weaver says as we discuss a 2011 Scandinavian finding that ski technicians had up to 45 times as much fluorocarbon in their blood as nonskiers. “And for me, this is a career.”

Thanks to Weaver, fluoro wax is now banned from most Eastern Intercollegiate Ski Association races. Many U.S. high school leagues likewise allow only cheaper, slower hydrocarbon-based wax, in part because pricey fluoro advantages wealthier athletes. The bans are tough to enforce, though, since there’s no inexpensive way to test whether a ski is fluorinated. Last year, after the Norwegian Ski Federation banned fluoro from all races for kids 16 and younger, it paid a lab about $6,000 to swab 48 skis, one each from 48 youth racers. Twelve skis carried “strong indications” they’d been treated with fluorine; 12 more carried “indications.” Do these results mean that Norwegian children are disproportionately evil? Not necessarily. The nascent test is hypersensitive; even using a fluorocarbon-tainted wax brush on a ski could yield “strong indications” of cheating.

The governing body of Nordic skiing’s World Cup circuit, the Fédération Internationale de Ski, has no plans to prohibit fluoro use. Key World Cup races draw about 14 million European television viewers. The world’s top Nordic skiers, Johannes Klaebo and Therese Johaug, both Norwegian, make about $1 million a year. With this kind of lucre at stake, a question looms: What sort of desperate measures will the pros take when fluorinated wax is illegal to bring into Europe, where most races are held?

Some ski savants are battening down for a dystopian future. “I’ve got to believe there’s going to be a black market,” says Gardner, the ex-coach, who now runs a Vermont-based sports marketing firm. “Will people cheat?” asks one ski store owner, begging for anonymity. “I know they’re capable of it, because I sell the wax.”

Myself, of late, I’ve been thinking about this half-used bar of fluoro that sits in my basement, glinting like a contraband gemstone. The European Chemicals Agency advises against taking fluoro to a landfill (it’ll just leech), so I’m going to use it in my next race. Why not? One more hit of eerie, unnatural speed—that’s all I ask, just one more hit.

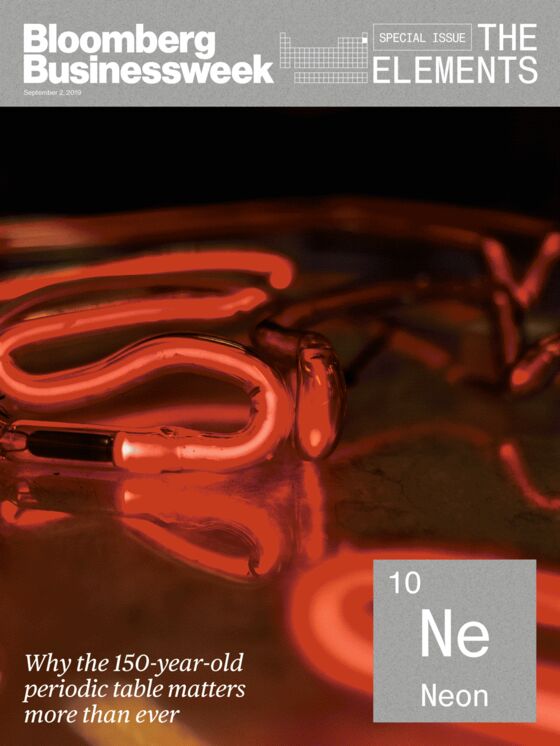

This story is from Bloomberg Businessweek’s special issue The Elements.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Dimitra Kessenides at dkessenides1@bloomberg.net, Jeremy Keehn

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.