The Crisis at South Africa’s $150 Billion State-Owned Fund Manager

The Crisis at South Africa’s $150 Billion State-Owned Fund Manager

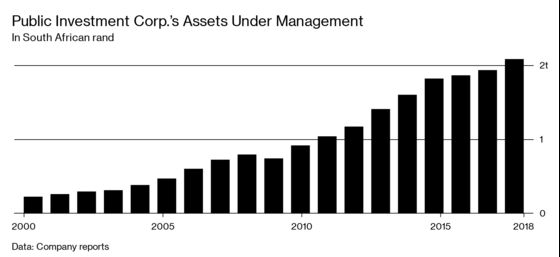

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Africa’s largest fund manager used to be a success story. Owned by the South African state, the Public Investment Corp. runs money for public institutions including the government-worker pension fund covering more than 1 million people. It increased its assets under management sixfold in 15 years, to about $150 billion. It's a major player in the Johannesburg stock market, and has wielded its power to curb executive pay at companies, make or break takeovers, and drive the government agenda of boosting black participation in the economy.

Now the 108-year-old asset manager’s existence—at least in its current form—is under threat. A series of scandals and multiple allegations of political interference in investment decisions have been exposed by a judicial commission of inquiry created by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa. The PIC also holds a fifth of the debt of the troubled state-owned power utility, Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd.

The PIC’s management is in upheaval. The chief executive officer of four years left in November, and his replacement was suspended in March for allegedly interfering with the commission’s investigation. The head of publicly listed investments was suspended over one of the deals undertaken by the fund. Both of the suspended executives have denied wrongdoing. The PIC’s board resigned in February after allegations of wrongdoing were made by an anonymous whistleblower against some members, who weren’t named in the board’s letter of resignation. An interim board was put in place only this July.

At stake is not only the performance of the PIC’s funds but the financial health of the South African government. Ninety percent of the money the PIC runs comes from the Government Employees Pension Fund. The GEPF’s payouts are guaranteed by the government and therefore by the South African taxpayer. If the government had to take these over, it would place yet another fiscal burden on Ramaphosa’s government, which is already struggling to maintain the nation’s credit rating and bail out indebted state companies. “It’s a critical organization,” says Iraj Abedian, CEO of Pan-African Investments and Research Services, who has advised the government in the past. If returns generated by the PIC can’t cover pension payouts, “it would become an absolutely phenomenal catastrophe that government cannot get out of,” he says.

So far returns haven’t suffered. In its 2018 annual report, the GEPF said its funds, almost all of which are invested with the PIC, grew by 153 billion rand ($10.8 billion), or 8.5%. It has a 108% funding level—that is, it has 8% more than it needs to pay promised benefits. But Ramabu Motimele, a senior human resources official at the PIC, told the commission that morale has plunged amid “mistrust and fear.” The PIC’s head of private equity has left along with the fund’s top economist. Former and current PIC executives, who asked not to be named because of ongoing labor, disciplinary and legal processes, say the turmoil has frozen decision-making at the level immediately below the executive committee. Employees spend their workdays watching live footage of the commission, before which more than 70 witnesses have delivered sometimes conflicting accounts of misconduct, political interference, and corruption.

The PIC even faces the possibility of losing its biggest customer. Abel Sithole, the principal executive officer of the GEPF, told the commission this month that his fund isn’t obliged to have its money managed by the PIC. Meanwhile, the Public Servants Association, the biggest labor union sending funds to the GEPF, is campaigning for the pensions of its members to be divided among private fund managers.

Allegations of political interference date back to the rule of President Thabo Mbeki. The PIC helped found the Pan African Infrastructure Development Fund in 2007 just as the South African leader was driving his “African renaissance” agenda of investment throughout the continent. During the scandal-marred years of President Jacob Zuma, the GEPF launched a developmental policy that allowed up to 5% of its assets to be used for social infrastructure—such as schools, hospitals, and low-cost housing—and boosting black economic empowerment. Many deals now under scrutiny by the commission fall under this policy. Daniel Matjila, who departed the CEO post in November, also testified that the PIC lost $333 million by investing in Erin Energy Corp., an oil company, whose founder was a friend of Zuma’s.

Another investment under scrutiny: the PIC’s funding in 2017 of Ayo Technology Solutions Ltd., a company linked to a businessman who claims close links to the ruling African National Congress. Prior to the company going public PIC paid 4.3 billion rand for a 29% stake in Ayo, a holding that today is worth 900 million rand, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Matjila told the commission that the Ayo investment hasn’t performed as anticipated due to deals Ayo was expected to make not taking place, negative media reports and commission testimony, and litigation. Ayo has stood by its valuation and said it was continuing to implement the strategy it had laid out before its initial public offering.

The very structure of the PIC lends itself to political interference: The deputy finance minister has traditionally served as chairman. That practice was only broken with this month’s naming of the interim board and the July 25 appointment of businessman Reuel Khoza as chairman. Khoza is a former chairman of Eskom Holdings and Nedbank Group Ltd., one of South Africa’s largest commercial banks. The most recent deputy minister and PIC chairman, Mondli Gungubele, forced Matjila out of the CEO post after he refused to go along with a proposed investment in struggling retailer Edcon Holdings Ltd. that would have helped secure 140,000 jobs, Matjila told the commission. Several months later, after labor allies of the ruling party threatened to discourage its 1.8 million members from voting for the ANC in May elections unless Edcon was saved, the PIC led a rescue with a 1.2 billion rand investment.

Gungubele on several occasions told PIC executives that he was there as a representative of the ANC, and had to be reminded of his responsibilities as a supposedly independent chairman, say members of the executive committee who asked not to be named because of ongoing labor and legal disputes at the fund manager. Gungubele said in a statement to the commission that it had been the board’s collective decision that Matjila be asked to leave immediately because he had expressed a desire to depart at the end of his contract. He didn’t respond to requests for comment on his role at the PIC.

Matjila himself supported another controversial investment: buying 90 billion rand of debt in Eskom, a utility that doesn’t generate sufficient revenue to cover its running costs. Eskom has had to have the majority of its debt guaranteed by the government, is in the process of receiving a multibillion-dollar state bailout, and may be split into three divisions under a plan from Ramaphosa. Buying that much Eskom debt “is a poor investment decision,” Abedian says. “There’s no exit strategy. To position the fund manager as a lender of last resort is just bizarre and very unwise.” Matjila said in testimony that Eskom is crucial to the South African economy, and the PIC’s success depends on the economy’s health.

Power struggles between executives over positions and pay packages that ranged from $1.1 million for Matjila to $360,000 for the head of human resources may have added to the PIC's the problems. Last year an organizational chart seen by Bloomberg was passed among some executives showing who was to be ousted, including Matjila, and who they were to be replaced by—months before the suspensions and departures took place. Deon Botha, head of corporate affairs at the PIC, said the PIC is not aware of the chart, and that the suggestion of infighting over positions is “speculative and imaginary.”

For now the asset manager, three times the size of its nearest South African competitor, is in limbo. The GEPF has reined in the discretion on investments the PIC can exercise by saying all non-publicly traded investments over 2 billion rand must go to the GEPF board of trustees. The previous limit was 10 billion rand. “We want a complete overhaul of the mandate of the PIC, but secondly we want an opening in terms of the percentage of the investment that goes to the PIC and other fund managers,” says Tahir Maepa, one of two deputy general managers of the Public Servants Association. “The purpose of investing is to make money. It’s clear that the PIC has been a cash cow for a number of people.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net, Anne Swardson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.