America’s Economy Faces a Zombie Recovery, Even With Vaccine

America’s Economy Faces a Zombie Recovery, Even With Vaccine

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- This was supposed to have been a good year for zombies. At least that’s what Kevin Kriess, owner of the Living Dead Museum and Gift Shop in Evans City, Pa., thought. The business, not far from the cemetery where George Romero filmed the 1968 zombie classic Night of the Living Dead, was gearing up for an expansion. Kriess planned to open a second location at a mall a 45-minute drive away, where the sequel Dawn of the Dead was set. “This year was going to be super big for us,” says Kriess, a horror-movie buff turned purveyor of T-shirts, posters, and other memorabilia to obsessed fans of the undead.

Instead, in October, Kriess packed up his ghoulish wares and turned off the lights for the last time in the storefront he had rented across from a funeral home, another victim of a pandemic that has upended lives around the world.

With 300,000 dead and millions displaced from their jobs, what Kriess is going through hardly registers on the economic damage scale. But his story is representative of the broader experience at the end of a calamitous year. Much of the economy remains in suspended animation—a zombie recovery—that masks how much the crisis has curtailed ambitions and how much depends on a new injection of government aid that has languished for months in a partisan Congress.

Hope is on the horizon in the form of a vaccine. But an economy that seemed over the summer to be roaring back to life is facing a dark winter. In November, the U.S. created just 245,000 jobs, a pace at which it would take three and a half years to get employment back to February’s levels. Now, as cases of Covid-19 and deaths from the disease surge to record highs, states are imposing new restrictions.

The U.S. economy is likely to end the year almost 3% smaller than at the start. That’s not bad considering where things stood in the second quarter, when output collapsed at an annualized rate of more than 30%. But for Kriess and many other business owners who went into 2020 thinking they’d be riding an expansion, it feels worse. At the beginning of 2020, the U.S. economy was expected to grow by at least 2%. That means it’s closing the year roughly 5% smaller than it would have been.

As with the virus, the impact of the Covid-19 recession has been unequal. Although millions of people in the leisure and travel industries remain out of work, other Americans will emerge unaffected economically, and perhaps better off.

That pattern holds true in Butler County, which straddles the suburbs and exurbs of Pittsburgh, including Evans City. In October, the county had an unemployment rate of 5.9% compared with 6.9% nationally. But scratch the surface, and you discover all the little ways the local economy is hurting.

Down the road from the Living Dead Museum, at a restaurant painted Pittsburgh Steelers black and gold, Deb Collins has watched revenue collapse. Business at Sports & Spirits is down 60% this year, she says, making 2020 the worst since she and her husband bought the place two decades ago. The surge in new cases has her worried that many small businesses like hers won’t make it through the winter, especially after Pennsylvania responded by again suspending indoor dining. “We’re hunkering down, just trying to stay afloat,” she says.

At Fibercon International Inc., a family-owned company in Evans City that makes bobby-pin-thick strands of steel to reinforce concrete floors and walls, orders are off by about one-third this year, according to Kevin Foley, vice president of sales and marketing. The company, which received a $162,300 federal Paycheck Protection Program loan in the spring, has managed to avoid laying off any of its 18 workers. Its products are used in new factories and warehouses around the world, so Fibercon’s order book is a bellwether—and the signal is not good. One project for a major retailer has been put on hold, Foley says, and a client that builds industrial parks has halted new construction. Orders are slow going into next year, and the company’s sales team isn’t traveling. “It’s a weird situation right now because our business is based on meet and greet, being out in the field,” Foley says. “And we’re landlocked.”

Butler County has seen industries rise and fall. Evans City began life as an oil town. Butler, the county seat, was once home to Pullman-Standard, which made many of the U.S.’s railroad carriages last century. The county went into the pandemic having found a healthy 21st century balance. Cranberry Township, at the junction of two major interstates and a 20-minute drive from downtown Pittsburgh, has been one of the city’s fastest-growing suburbs for decades and built a brand as a low-tax alternative for corporate headquarters. But the county also prides itself on its manufacturing base.

That mix has helped it avoid the hit that many other communities have taken. Yet Butler County went into the closing months of 2020 with about 5,000 fewer people working than in February, a dip of 5% that took the ranks of the employed in the county down to 90,000, a level last seen in 2012. Most of those who haven’t gotten their jobs back were in the leisure and hospitality business or in health care, says Leslie Osche, chair of the county board of commissioners. If all goes well, she says, they should be back at work within 18 months to two years.

Still, Butler County is facing longer-term questions. The fate of an AK Steel plant on the outskirts of Butler that bills itself as the only U.S. producer of electrical steel used in transformers remains uncertain. The Trump administration this year opened a national security investigation that could clear the way for new tariffs on imports of this type of steel. “We saved 1,400 jobs at AK Steel, right here in Butler,” Trump said when he campaigned in Butler a few days before the election.

In a statement at the time, Cleveland Cliffs Inc., which bought the plant as part of a merger with AK Steel this year, indicated that the Trump administration had promised all sorts of actions. But neither the White House nor the Commerce Department have made any substantive moves. The only thing the administration has announced is an agreement with Mexico for greater monitoring of exports of electrical steel. So the fate of the plant may hang on what President-elect Joe Biden’s administration chooses to do.

The same sort of uncertainty hangs over other key elements of the local economy. Will there still be demand for all the midlevel office buildings in Cranberry Township? And for the restaurants, hotels, and other services that have sprung up to cater to the people those offices attracted?

Employees have been quicker to return to work in suburban offices where they can commute by car and don’t need to take elevators, says Jeremy Kronman, vice chairman of commercial real estate firm CBRE Group Inc.’s Pittsburgh practice. But companies are also making long-term adjustments. Westinghouse Electric Corp., whose headquarters campus accounts for about 1 million of the 4.5 million square feet of office space in Butler County, is reducing its footprint, Kronman says.

It’s a move many companies across the U.S. are considering and one of the reasons that Richard Barkham, CBRE’s chief economist, thinks the market for office space will lag the broader recovery in the U.S. in 2021. But it also sits next to other questions that are unanswerable for the time being.

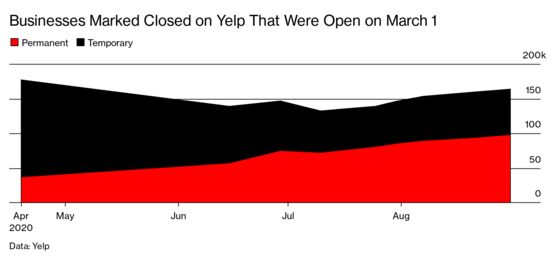

Thanks to government action, many metrics of economic pain, such as bankruptcies and evictions, look better than they did before the pandemic. But economists like CBRE’s Barkham say that government help is just holding back a tide that may be unavoidable in the end—too many companies can’t last for long in an environment of reduced demand.

This state of suspended animation applies as well to corporate America, which has benefited from the Federal Reserve’s dramatic cuts in interest rates and moves to support credit markets. A Bloomberg analysis of financial data for 3,000 of the country’s largest publicly traded companies found that 1 in 5 were not earning enough to cover the cost of servicing the interest on their debt, rendering them financial zombies. Collectively those companies—among them Boeing, Delta Air Lines, Exxon Mobil, and Macy’s—have added almost $1 trillion in debt to their balance sheets since the beginning of the pandemic.

At the Salvation Army in Butler, evidence of this odd equilibrium can be seen in requests for food assistance. They’re down this year, largely because of drive-through distributions done by other charities in the Pittsburgh area. That doesn’t mean all is well. Applications for help paying for heating and other utility bills are up 50% from last year, says Darlene Means, who runs the local chapter of the charity with her husband.

Fewer petitions have been filed in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court’s Western Pennsylvania District than last year, but signs of how the crisis is rippling through the local economy can be found in its records.

Ed’s Beans Inc., a coffee roaster in Cranberry Township that owns the regional Crazy Mocha chain, filed for bankruptcy in October. The company secured a $506,200 PPP loan in early April, but it succumbed to the reality that fewer people going to the office meant fewer cups of coffee sold. It owed millions of dollars to creditors, including almost $39,000 to a local bakery renowned for its doughnuts. In November, it asked the court to allow it to stop paying rent while it looked for a buyer for the Crazy Mocha chain. Just seven of its 23 stores were open for business. But it wasn’t willing to give up on the closed stores, leaving those locations in their own undead state. “The debtor submits that reopening the closed locations at this time is not financially advantageous,” the company’s lawyers wrote. Owner Ed Wethli declined to comment.

Barkham thinks that pattern will be replicated on a wider scale next year. As the economy comes back to life and government support eventually is withdrawn, one effect is likely to be a surge in bankruptcies and evictions, he says. Even if vaccinations reach a meaningful number of Americans, it may be too late for many businesses.

It’s not clear how long Kriess, the memorabilia dealer, will be able to stay on his feet in the zombie recovery. He says he hopes to bring the museum back to life next year in the Monroeville Mall, where in early November he opened what for now amounts to little more than a kiosk selling T-shirts. He’s also planning a July 2021 festival.

Any return to the ambitious goals from the start of the year seems far off, though. He needs zombie tourists to come back to Pittsburgh. He also needs to be able to travel to fan festivals and industry conventions, which accounted for a significant portion of his income. “If the conventions don’t come back for a while, it’s going to be a struggle,” Kriess says. “If they do come back, and the vaccines work, then we probably will go back to normal. But that’s still to be seen.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.