Covid Plus Decades of Pollution Are a Nasty Combo for Detroit

Covid Plus Decades of Pollution Are a Nasty Combo for Detroit

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It looked like an ordinary drive-by parade. The kind that people in locked-down states have been holding this year to celebrate births and graduations. Cars rolled slowly down the street, their drivers honking and waving, stopping for brief chats. There were balloons and a banner: Welcome Home.

The July celebration was festive, but it was also a reminder of all the ways Covid-19 had devastated this Southwest Detroit neighborhood. Theresa Landrum was there to salute her niece, Donyelle Hull, who’d won a touch-and-go battle against the virus—doctors at one point told her son to start planning her funeral. Hull, who’s 51, spent 61 days in Beaumont Hospital and an additional 45 days in rehab learning to walk again.

This wasn’t the only welcome-home parade Landrum had been invited to. She counts at least 10 friends and neighbors who’ve recovered from the virus. And she has another list, of those who didn’t make it: a pastor, a state legislator, a neighbor couple who passed away within weeks of each another. “You can’t even grieve,” Landrum says. “You just harden yourself so you don’t get that feeling of hurt.”

She doesn’t think it’s a coincidence that so many people she knows have had severe cases of Covid. She attributes it to something quite obvious: the air they breathe. Her ZIP code, 48217, is one of the most polluted in Michigan. And researchers have begun to confirm that pollution can worsen the effects of the illness. A study out of Harvard, for example, has shown that Covid death rates are higher in populations with more exposure to pollutants, and international research has demonstrated that some of the hardest-hit parts of Europe are in especially polluted areas.

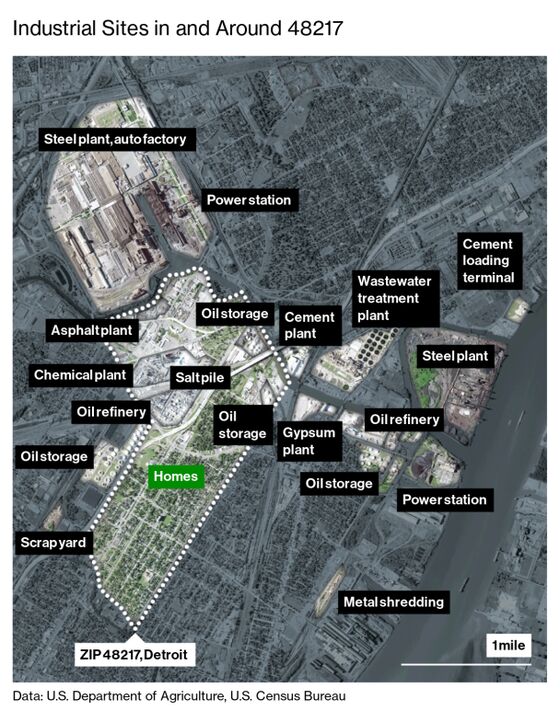

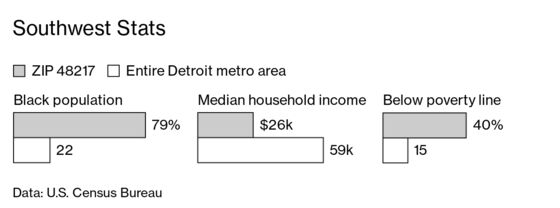

For decades, Black Americans like Landrum, who’s in her 60s and describes herself as a 48217 environmental-justice activist, have fought to limit industrial emissions in their neighborhoods. More than two dozen industrial sites surround hers. People in 48217 live on average seven fewer years than in the country as a whole, and asthma hospitalization rates in the area are more than twice as high as those of Michigan and about five times higher than those of the U.S.

Generations of activists in Southwest Detroit say they’re tired of living under a cloud. They’ve demonstrated, filed petitions, shown up at public hearings, and watched as industry won regulatory victory after regulatory victory. This summer, as the Black Lives Matter protests raged, residents of an overwhelmingly minority Detroit-area neighborhood filed a civil-rights complaint related to the approval of a hazardous-waste storage facility’s ninefold expansion, arguing that pollution is a form of racism, too.

Michelle Martinez, acting executive director of the Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition, says activists have been “screaming for decades” about the consequences of industrial expansion but haven’t been taken seriously. “The pollution and the smokestacks are a form of slow violence.”

A ring of heavy industry encircles Landrum’s neighborhood, a 2-mile-long residential pocket of Southwest Detroit where the median home price is $48,100. Some 80% of the 6,887 residents of 48217 are Black, and 40% of all residents live in poverty. The area is surrounded by mills run by U.S. Steel and the mining company Cleveland-Cliffs, as well as DTE Energy’s River Rouge coal-fired power station, a Great Lakes Water Authority treatment facility, an oil refinery, a drywall manufacturer, a salt pile, a lime quarry, three scrap-metal processors, a chemical plant, four concrete suppliers, an asphalt maker, Ford’s River Rouge production facility, cars spewing exhaust on Interstate 75, and diesel trucks rumbling up and down the streets belching so much dark dust that other drivers sometimes have to pull over because they can’t see the road.

Neighborhoods like this sprung up by design. A century ago, Detroit was a magnet for Black Southerners who were flocking northward for steady jobs in heavy industry. But redlining ensured that only Whites could live in the city’s more desirable neighborhoods, and segregation was enforced with such zeal that in 1941 developers built a half-mile-long, 6-foot-high wall to keep minorities out of a White area. (Sections of the wall remain standing to this day.) Black people settled in Southwest Detroit, in ZIP codes like 48217, in the shadow of Ford Motor Co.’s sprawling manufacturing complex. In its heyday, Ford employed more than 100,000 workers there. Today, the number is 7,500.

Landrum’s father tore down coke ovens for a living. Growing up in 48217, she’d shake off his coveralls in the yard after work, not knowing the dust contained asbestos. She didn’t think there was anything unusual about a sky tinted orange by smoke. And when silver or black fallout from local mills would coat the neighborhood, she and her friends would write “wash your car” on automobile windows. Nobody thought anything of it.

That changed for her in the late 1990s. Landrum was at a hair appointment when she heard a loud boom. No one in the salon flinched. “I said, ‘Wait a minute, did you all hear that?’ They said, ‘It’s been going on awhile.’ ” She and her neighbors were also noticing cracks in the foundations of their homes, sunken spots in their yards, and broken windows. They traced the reason to a lease granted in 1999 by the city to Detroit Salt Co., allowing it to extract salt from 1,500 acres of public property. The process involved the use of explosives some 1,200 feet underground, according to a 2003 Detroit Metro Times article. Landrum and her fellow residents succeeded in forcing the company (which didn’t respond to requests for comment) to reroute its blasts. It was her first foray into the kind of activism that would shape the next decades of her life.

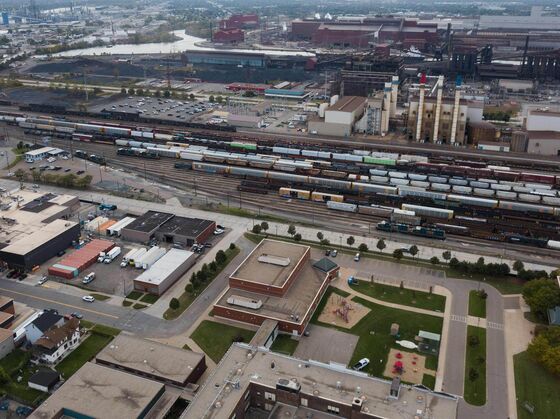

One of Landrum’s most consistent antagonists has been a steel mill built almost 100 years ago by Ford. It stands across the street from the playgrounds of the Salina elementary and intermediate schools in neighboring Dearborn. The plant was sold in 2004 to Severstal, a Russian steelmaker. Ownership has changed hands twice since then, but the auto industry has remained a prime customer. The mill’s violations have been so numerous that state regulatory staff, who are responsible for enforcing federal and state environmental laws, have called it “by far the most egregious” facility in Michigan, according to internal emails uncovered by lawyers battling the mill’s owners.

Even so, officials have continued to grant permits allowing the mill to pollute. Case in point: In 2014, Severstal was allowed by Michigan’s regulator, the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), to substantially increase its emissions. A group of community members fought back, filing a case that dragged on even as Severstal sold the mill to Ohio-based AK Steel Corp. that same year. (Severstal says it needed to increase emissions because of construction projects at the mill.) In 2015, as part of a settlement in a separate legal matter related to the mill’s pollution, AK Steel agreed to install air-filtration systems at the Salina schools. Since then, Michigan has cited the facility 13 times, including twice this year, for environmental violations such as emitting too much lead and manganese.

Residents’ complaints about pollution from large plants routinely led to violation notices last year, sometimes as many as four a month. At least three times, EGLE cited AK Steel for soot that ended up in the surrounding neighborhood. In one instance, starting in the late afternoon of Oct. 19 and extending into the next day, 11 residents complained of it falling on their homes, yards, and cars.

This January the situation for residents threatened to get even worse: AK Steel filed an application requesting permission to triple the plant’s lead and manganese emissions. “I don’t know if they were having a meeting and somebody said, ‘Does somebody want to see a funny joke?’ and submitted the permit” application, says Justin Onwenu, a Sierra Club community organizer.

Tyrone Carter, a Michigan state representative and Covid survivor who lives right by I-75, says polluters don’t have much trouble getting permits in Southwest Detroit. He doesn’t recall a time when the state regulator denied one. “They’d have a hearing, you’d go, you’d voice your complaint, you’d do it in writing, we as a community would show up, and then they’d get a permit anyway,” he says. In the past decade, EGLE has approved 3,586 applications statewide and denied 18.

People who live near plants say the onus is on them to prove the companies are doing harm. “It’s so backwards,” Onwenu says, recalling meetings where resident after resident got up to talk about their health problems. “Why isn’t the company here telling us their operations are safe? The community shouldn’t be the ones under scrutiny for the experiences they’re having.”

Lung cancer rates in Wayne County are 27% higher than the national figure, but the system isn’t set up to hold polluters accountable for such issues. “It’s almost like an impossible task to prove that you’ve suffered harm, because the legal framework requires you to associate a specific cancer to a single contaminant,” Martinez says. “When you start piling on smokestacks with freeways with soil contamination with water contamination, the cumulative impact is enormous.”

That’s another quirk. When considering an emissions permit, the state regulator doesn’t always account for the totality of what’s affecting a given neighborhood. That means more than one factory can get state approval if its emissions of, say, particulate matter are under the legal limit. The same is true, in most cases, on the federal level. “Our Clean Air Act does a pretty bad job of addressing that issue,” says Nick Leonard, executive director at the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center. “It commonly looks at facilities facility by facility, and pollution as pollutant by pollutant, and doesn’t get at this issue of a number of facilities being in a small area.”

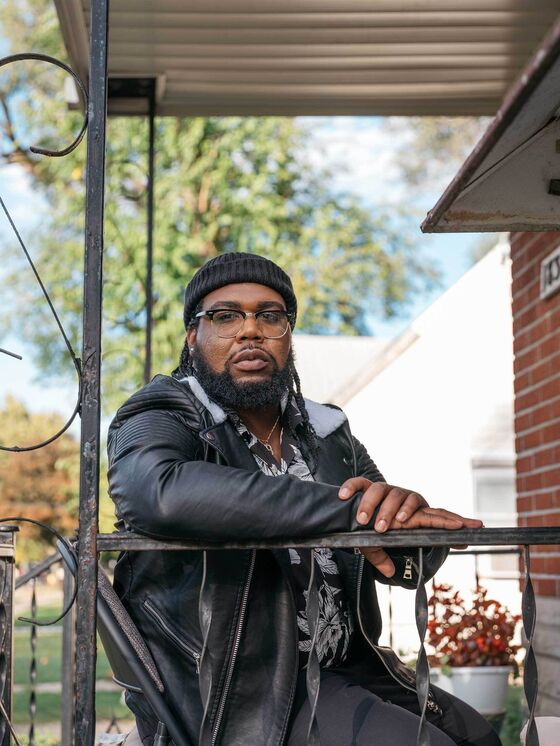

On the afternoon of March 23, De’Andre Tucker, a 34-year-old aspiring fashion stylist and former autoworker, was being treated for Covid at Henry Ford Hospital when he tried calling his mother—Landrum’s niece, Donyelle Hull. No answer. He tried again. No answer. The two are very close. They live together and talk three or four times a day.

Tucker wanted to let Hull know he’d tested positive and been admitted. Now he was getting nervous. Finally he decided he’d have to check himself out of the hospital to investigate. “I got in the car, and I drove 90 miles per hour,” Tucker says. When he got inside the house, he saw his mother lying on the couch, foaming at the mouth. “I screamed, and I fell to my knees,” he says. “I thought my mom was not here anymore.”

Then Hull surprised him, using her nickname for him to ask, “Byrd, what’s wrong?” She left the house in an ambulance. Tucker followed her to Beaumont Hospital and ended up admitted as well. Hull was soon being kept alive with a ventilator. A doctor told Tucker to prepare for the worst and said that if his mother did pull through, she wouldn’t remember him.

Although they were in the same facility, Tucker never saw her. He was discharged from Beaumont, then ended up back at Henry Ford, then was discharged again and told to quarantine for eight weeks while he recovered from Covid-related pneumonia. All the while he was getting updates about Hull. Her heart rate spiked. She had pneumonia and other infections. She’d been placed on dialysis. Her liver was shutting down. “It was the scariest time of my entire life,” he says.

At one point Tucker asked to be put on the phone with Hull even though she was on a ventilator. He spoke through tears. “I said, ‘Please do not give up, I know this is a lot on your body.’ I said, ‘If you cannot fight any longer, I understand, because you have been through so much. But I don’t want you to give up.’

“You know,” he continues, “the very next day the doctor called me and told me they were going to take her off the ventilator?”

Many explanations other than pollution have been floated for Black Americans’ increased vulnerability to Covid: Black people are more likely to have chronic illnesses such as diabetes and high blood pressure, which can magnify the virus’s effects; many work in frontline jobs in grocery stores, public transit, and residential care, where they face more exposure; and there’s been documented reluctance of doctors to believe Black patients when they describe the severity of their symptoms. Tucker himself was turned away the first time he showed up at the hospital for a test, even though he was having trouble breathing and had a confirmed exposure to Covid.

Scientists are increasingly certain, though, that bad air plays a role in the coronavirus’s course. “We think the immune response to the virus is weakened by air pollution exposure,” says John Balmes, a pulmonologist and professor of medicine and environmental health sciences in the University of California system. Cells in the lungs release cytokines, which normally help a person fight off infection. But when a person’s lungs are loaded with particles, the body’s defenses become dysfunctional. “The virus cannot be contained,” Balmes says.

Some of the most in-depth early studies about Covid and pollution have come from outside the medical field. Francesca Dominici, a professor of biostatistics at Harvard, has spent decades authoring studies showing that Black Americans breathe poorer-quality air and that this is linked to adverse health. In April she published an article connecting increases in the death rate from Covid with even modest increases in long-term pollution exposure. “If you live in a community where you’ve been exposed to all kinds of toxicants and air pollutants, we know that your lungs have been inflamed for a very long time before, and if you contract the virus, your ability to respond to the virus is compromised,” Dominici says. “Air pollution could be one of the major contributing factors why we observe this much higher rate of Covid mortality among African Americans. It’s not the only factor, but it’s a very important one.”

The study thrust Dominici into the spotlight in a way her prior research typically hadn’t. She was invited to speak to Congress and in May joined Democratic Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey and a minister from Louisiana’s so-called Cancer Alley for a webinar on high rates of illness stemming from exposure to air and water pollution.

Dominici’s study focused on PM 2.5, short for particulate matter that’s 2.5 microns or smaller—at least 30 times smaller than the average diameter of human hair. Sources of PM 2.5 are everywhere: vehicles, smokestacks, cigarettes, vape pens, forest fires. Most of the bad stuff people inhale gets caught in the upper respiratory tract, where mucous can catch it and a cough can sweep it out. But PM 2.5 is tiny enough that it can journey deep into the lungs, where it can do the most damage—and where it might be meeting up with the coronavirus.

Other scientists have also highlighted the idea that pollution can affect Covid outcomes. Yaron Ogen, a postdoctoral researcher at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg in Germany, normally uses satellite images and remote sensing data to evaluate the chemical composition of the Earth’s surface. His research involves classifying and quantifying Mongolian minerals, which got him thinking about how the virus might thrive in different environments. “Since March, the distribution of fatalities was not equal,” he says. “It was mostly located in China, in a certain area of China, in Iran, Italy, and Spain. It wasn’t Rome, it wasn’t Barcelona. As a geographer, I was asking one simple question: ‘What do they have in common?’ ”

The hardest-hit cities, like Madrid, Milan, and Tehran, are near mountains or hills, which can trap pollution. So Ogen used satellite data that monitors nitrogen dioxide—a gas emitted by vehicles and power plants—to see whether there was a correlation between pollution levels and the number of deaths. What he found was fairly clear: Of the 4,443 deaths by March 19 in 66 regions in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain, 78% were in five of the more polluted parts of Italy and Spain. Only 1.5% of the deaths occurred in the least polluted regions of those surveyed.

Ogen would like to see medical doctors drawing on this sort of information when they evaluate a patient’s health. “We need to cooperate, the two different disciplines,” he says. “The healthier the environment, the healthier we are as people.”

Few medical centers in the U.S. have departments dedicated to the effects of air pollution. There’s little recognition of how industrial emissions affect an individual’s health, despite consensus that they cause damage broadly. Vicki Dobbins, a friend of Landrum who lives in River Rouge, a town bordering 48217, was hospitalized with Covid for four weeks this spring. She points out that conversations with doctors tend to center on personal habits, as if getting sick could be the patient’s fault. “The doctors never ask you ‘Where do you live? What water do you drink? What water is around you? What kind of chemical are you ingesting?’ ” she says. “They just ask you ‘Did you smoke, did you drink, did you take drugs?’ ” More than two months after Dobbins got her diagnosis, she still has to pause to catch her breath just to finish a sentence.

Residents of 48217 scored some victories earlier this year. Marathon Petroleum Corp.’s refinery, which is within walking distance of Tucker and Hull’s house, was forced to pay the community $82,000 in fines for emissions releases and $280,000 for environmental remediation in Southwest Detroit. These are substantial sums for residents, if not much compared with the $3.3 billion Marathon investors received in dividends and share buybacks in 2019. Much of the $280,000 will go toward an air-filtration system for a third local public school that sits in the shadow of heavy industry.

Jamal Kheiry, a spokesman for Marathon, defends the refinery’s environmental record. “Our commitment to being a good neighbor has driven our success in dramatically reducing emissions from our production processes and the use of our products,” he says. “Our Detroit refinery has operated at more than 40% below its yearly permitted emission levels for the past 15 years, and we have reduced its emissions by 80% over the past 20 years.”

Marathon has made financial contributions to the community in the past. After a planned $2.2 billion refinery expansion drew criticism from activists such as the Sierra Club, the company struck a deal with the city that included a $2 million donation to rebuild the Kemeny Recreation Center while it moved ahead with the expansion. The center has become a bedrock of the neighborhood, offering Halloween parties for kids, exercise classes for seniors, and baseball diamonds whose fields end at I-75, just across from the refinery.

Some residents see these efforts as greenwashing. Dolores Leonard, who’s been fighting for better air quality alongside Landrum since the late 1990s, volunteers at the center a few times a week. She noticed last year that staff were wearing Marathon-logo sweatshirts, freebies from community events hosted by the energy giant. “I took it personally that Marathon was trying to come across as a good neighbor when in fact they’re killing us every day,” she says. Leonard asked the staff members for their sizes so she could get sweatshirts advertising the Kemeny Recreation Center instead of Marathon. “You think that something is free,” she says. “It’s not free.”

The neighborhood saw some productive corporate engagement this summer, after AK Steel was acquired by Ohio-based mining company Cleveland-Cliffs Inc. in March for $1.1 billion. The new owners of the local mill held a meeting with community leaders in June. State Representative Abdullah Hammoud of Dearborn came away impressed with Cleveland-Cliffs’s willingness to listen to neighborhood concerns—which he views as a stark change from AK Steel’s approach. “We’re cautiously optimistic,” Hammoud says.

Afterward, Cleveland-Cliffs agreed to withdraw the mill’s application to triple its lead and manganese emissions. “There’s a history of misunderstandings and deceptions with the community,” says Lourenco Goncalves, Cleveland-Cliffs’s chief executive officer. “We’re fixing everything. We don’t want to pollute more, we want to pollute less.”

Still, Landrum is amazed that the mill continues to operate despite its history of violations. Were a meat-packing plant cited for E. coli contamination, it would get shut down and cleaned up, then have to prove it’s safe to reopen, she says. “Come on now, why aren’t they doing that to industry?”

In recent months, Landrum has been attending more hearings than ever before—a byproduct, she speculates, of rollbacks to clean-air regulations that the Trump administration claims will help ease the economic devastation wrought by the pandemic. She’s on three, four, five Zoom meetings a day. Permit hearings, town halls, community advisory panels for companies like Marathon—sometimes she’s double-booked and splitting her screen to keep up. She feels obligated to be present on screen as much as possible because she knows some of her neighbors can’t join in to defend themselves. They don’t have internet. She likens her environmental-justice work to having two full-time jobs.

She’s still got her eye on that steel mill, too. Experience suggests to her that the fight isn’t over. “Guess what?” she says. “They’re coming back. They always do. Not one time in history have I known a company to withdraw their permit and not come back.”

Read next: Life and Death in Our Hot Future Will Be Shaped by Today’s Income Inequality

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.