Putin’s Been Stingy With Stimulus Because of Sanction Fears

Putin’s Been Stingy With Stimulus Because of Sanction Fears

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- During his decade-plus tenure as finance minister, Alexei Kudrin became President Vladimir Putin’s most trusted economist by keeping a lid on spending and salting away hundreds of billions of dollars in a rainy day fund that helped the Kremlin weather economic crises with confidence. Now the fiscal conservative says Russia should be spending more.

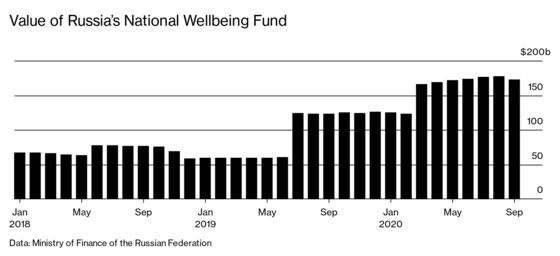

The Kremlin is turning a deaf ear, despite a 40% rise in the value of Russia’s National Wellbeing Fund this year. Putin doesn’t want to risk running down his savings now, even if it means starving the economy during the pandemic. That’s because after more than five years of escalating tensions with the U.S. and Europe, including countless rounds of sanctions, the Kremlin is digging in for more.

“The fund was set up to accumulate proceeds from high oil prices so that it could be used in difficult times,” Kudrin, who was finance minister until 2011 and now heads a government audit agency, said in an interview. “A pandemic is exactly that kind of situation.”

After Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, Kudrin was one of the few voices among the country’s elite arguing that the Kremlin should tone down its confrontational line to reduce the economic cost of an interventionist foreign policy that’s led to standoffs with the West over its meddling in the affairs of its neighbors, the Middle East, and foreign elections. But Putin wasn’t swayed—not even when Kudrin gave him a PowerPoint presentation showing the country risked slipping in rankings of global economies.

Putin brushed off Kudrin’s criticism again when asked about it at an investor conference on Oct. 29, saying any increases in spending would be done “very carefully” in order not to run down the country’s foreign exchange reserves. Unlike other major economies, “we can’t just hold out our hand for more money,” he said.

Putin spent most of his first decade in office paying down Russia’s foreign debt, in part to prevent creditors from using it for political leverage over the Kremlin. Lately the U.S. and the European Union have used sanctions to restrict borrowing by the government and state companies.

Russia dodged the worst of the coronavirus recession, thanks to an economy dependent on exports of commodities such as oil, gas, steel, and coal, which were unencumbered by lockdowns in cities. But the economic cost of Putin’s foreign policy is becoming clearer by the day as the government holds back on spending.

The government has boasted that fiscal stimulus this year amounts to almost 10% of gross domestic product. But Kudrin and other economists say the number is closer to 3%, making Russia one of the most frugal major economies in pandemic outlays. Much of the spending has been funded by borrowing from domestic banks, even as a slump in the ruble has boosted export revenue. As a result, savings in the government’s rainy day fund have climbed to $172 billion. The government plans to cut back borrowing in 2021 to tighten the budget, which has moved into deficit following three years of surpluses.

By contrast, ordinary Russians had to dig deep into savings to survive a six-week lockdown that ended in mid-May. By then, almost half of households had either no savings or just enough to cover expenses for four weeks, according to a survey by Moscow’s Centre for Strategic Research. Nochlezhka, a charity that hands out free meals from night buses in Moscow and St. Petersburg, says demand doubled in the spring and has stayed high ever since. Director Grigory Sverdlin says he isn’t optimistic the situation will improve anytime soon.

“Russia is now one of the only major economies pursuing austerity, and it’s pursuing it for the wrong reasons,” says Sergei Guriev, former chief economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Spending on health care and education as a share of overall public expenditure declined in the three years before the pandemic. Major infrastructure projects have also suffered from a lack of funding, especially in regions far from Moscow. Residents of Yakutia, in the far northeast of the country, have been waiting for 30 years for a bridge the Kremlin promised to build over Russia’s third-biggest river. Every year more than 600,000 people get stranded on one side when the winter ice gets too thin to drive on. Money that was meant to have been allocated for it got diverted to fund a $3.5 billion bridge to Crimea that was finished two years ago.

High oil prices helped Putin oversee a surge in living standards and average annual growth of 7% during his first eight years in power in the early 2000s. But the boom has given way to stagnation in the past decade. Since the Crimea crisis, the economy has expanded at an average annual rate of just 0.7%.

Putin started this year with a promise to give back a portion of the money that’s been squirreled away by spending about 2.1 trillion rubles ($27 billion) on infrastructure projects and benefits for the poor. Then the pandemic hit, and some of that money was channeled into support for industries affected by lockdowns.

The Kremlin has met with very little pushback, in large part because it’s careful to control the narrative on state TV that the policy of saving rather than spending is necessary to protect Russia from outside threats. When Putin’s approval ratings dropped to a record low of 59% during the lockdown, the government eased the restrictions instead of increasing financial support. “It’s almost like the politicians want to keep people poor so that all of their energy is focused on surviving, leaving no time to protest,” says Alexandra Suslina, a budget specialist at the Economic Expert Group, a Moscow think tank. “Improving living standards just isn’t a priority.”

Putin’s ratings improved with the economy over the summer, but now the government is facing another spike in coronavirus infections that’s threatening to run out of control in the absence of a new round of restrictions.

Meanwhile, the risk of new U.S. sanctions has increased. In the last debate before the Nov. 3 U.S. presidential election, Democratic candidate Joe Biden warned that any country interfering in the vote will “pay a price,” adding there was already evidence of Russian meddling.

Successive rounds of punitive measures since the annexation of Crimea mean there isn’t much left for the U.S. to target in Russia. One proposal put forward by a bipartisan group of U.S. senators would bar American money managers from taking part in auctions of sovereign ruble debt, limiting the pool of Russia’s potential investors to Europe and Asia and potentially increasing borrowing costs for the country. The International Monetary Fund and major credit rating companies have heaped praise on Russia in recent years for keeping debt levels among the lowest in the world and foreign exchange reserves among the highest. But Kudrin says that by maintaining that level of prudence in a crisis, the government risks dragging out the economic pain for years to come. “I imagine that they are being cautious with spending because they’re worried about future risks,” he says. “But it will be much harder to revive the economy later if it’s badly damaged.” —With Anya Andrianova and Aine Quinn

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.