The Pandemic Tears a Hole in a Vital Child Nutrition Safety Net

The Pandemic Tears a Hole in a Vital Child Nutrition Safety Net

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Luz Desiderio has long counted on free school breakfasts and lunches to help feed her four children. Today the cafeteria line is only a memory, like handshakes and movie theaters. In the pandemic, her kids are studying online at home, and she’s running out of cereal, eggs, and fruit. “I’m apologizing to my kids a lot, saying, ‘We don’t have that anymore,’ and they’ll have to wait until next week,” she says.

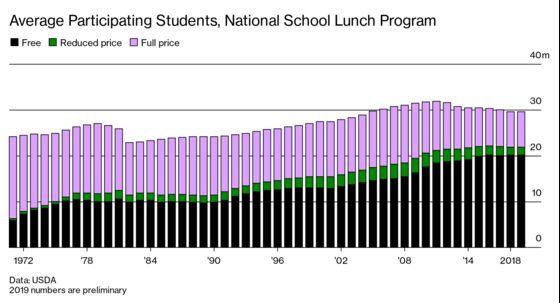

Covid-19 has taken a well-documented toll on the education of America’s children. But it also poses a less appreciated threat to their nutrition. The federal government spends $19 billion a year subsidizing school meals. The National School Lunch Program represents an essential strand in the safety net: It’s the second-biggest anti-hunger program after food stamps, now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

SNAP provides $646 a month for the Desiderio family in suburban Chicago, but that’s never quite enough. Luz’s husband, Alfonzo, buses tables at a Chinese restaurant. He makes $8 an hour, plus tips, but families aren’t eating out the way they were before the coronavirus. Luz, who emigrated from Mexico, is staying home with the kids. “When they used to go to school I felt relief, because I knew they were going to get fed,” she says in Spanish.

In a typical year, the government helps feed almost 30 million pupils a day, or about 1 in 2. Now, because of Covid-19, most districts are delivering half as many meals as before, or not even half, according to the School Nutrition Association, which represents school lunch program administrators. Many parents aren’t able to pick up food because of work logistics or having to watch kids during remote learning, and some schools provide meals only on certain days of the week.

These missed meals are contributing to an alarming increase in child hunger as food banks around the country report soaring demand. As of late June, 1 in 6 U.S. households was experiencing what researchers call food insecurity, surpassing the rate at the peak of the Great Recession, according to the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank. “When we first saw these numbers, I thought, ‘My God, they can’t be true,’ ” says Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, a Northwestern University economist who studies child poverty. “You think, ‘What is going on, America?’ This is a problem we can solve.”

In 1946, President Harry Truman signed the National School Lunch Act, declaring that Congress was “strengthening the nation through better nutrition for our schoolchildren.” Now the school food program, run by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, provides free meals for children in households with incomes below 130% of the poverty level, or less than $34,060 a year for a family of four. A family earning as much as 185% of the benchmark, or $48,470 annually, could get a lunch costing no more than 40¢.

As part of coronavirus relief, Congress gave the USDA the authority to make all families eligible for free school meals, regardless of income, through the end of the calendar year, a waiver the USDA has extended through June 2021. The agency also eased nutrition regulations so schools can offer grab-and-go fare such as burgers and baby carrots.

Given freer rein, districts are improvising. Over the summer, the Houston Independent School District bused boxes of fresh fruit and vegetables to pickup sites at about 20 apartment and housing complexes. But the program died in June when state money for delivering the food ran out.

Chicago’s public schools are letting parents pick up three days of food in a single visit. On a recent weekday in the city’s artsy Logan Square neighborhood, families gathered at the side door of an elementary school. A staffer asked how many kids each had and distributed bags of chicken patty sandwiches, chicken fingers, burgers, fries, apple slices, and chocolate milk.

In Bexley, Ohio, a Columbus suburb, the high school has taken a page from DoorDash and Instacart. Parents fill out an online order form and, from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. once a week, staffers drop off cheese ravioli, chicken fried rice, and other meals.

Both grab-and-go and delivery have a downside: food that’s less fresh and more processed. This backtracks on a federal initiative to improve school nutrition, a signature issue of former First Lady Michelle Obama. In 2012, thanks to revised USDA standards, American school menus got a makeover, including more whole grains and salad bars and less salt. The Trump administration has sought to dismantle that effort, citing red tape and food waste. But many districts have continued the push, leading to tough choices.

In Charleston, S.C., the district shut the salad bar, but it’s looking for a way to send salad packages home. “The further you get away from the kitchen, the harder it is to do a good job with your food,” says Ronald Jones, who directs health and nutrition for the South Carolina Department of Education.

The link between learning and proper nutrition is long established. Children whose diets deteriorate are also more likely to develop conditions such as Type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure, according to Caroline Dunn, a Harvard researcher who’s studied the pandemic’s effect on kids and hunger. “The long-term implications of this are really substantial for children who rely on the National School Lunch Program,” she says.

In Katy, Texas, schools, channeling McDonald’s, have opened drive-in windows from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. The menus of ham and cheese sandwiches and burgers might not meet the Obama standard. But there’s a bigger problem: Many poor households don’t have a car. Even middle-class ones might have only one and need it for commuting.

That’s the case for Jodi Legan, a mother of four in Katy. Her husband, Dietrich, a supervisor at a water bottle plant, needs the family car. “We don’t get the school lunch,” says their fourth-grader daughter, Layla. At school, “I could, like, make my salad and stuff, but now I can’t do that.”

Layla isn’t getting much salad at home these days, either. Her father makes about $40,000 a year with overtime, though his hours have been getting less regular. Her mother had to take a break from her job as a nursing assistant to supervise the kids’ online classes. She finds herself with no choice but to pick up the cheapest food she can find. “We used to be able to go and get fruits, vegetables. And now you can get a bag of chips at Kroger for a dollar,” Jodi says. “It’s sad, but that’s the tossup that you’re making now.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.