Border Blockades Spark Australia’s Biggest Crisis in 120 Years

Border Blockades Spark Australia’s Biggest Crisis in 120 Years

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The coronavirus pandemic is creating perhaps the biggest crisis for Australia’s federal system since 1901, when six disparate British colonies in the so-called Great Southern Land united to win collective independence. The country has never been as divided as it is now.

State borders that were previously little more than photo opportunities are now fortified in a bid to keep out residents from Covid-hit places. Separated family members are defying police orders by hugging each other across the barricades, and some Australians have been denied the right to retrieve their children or visit dying relatives.

In the densely populated southeastern part of the nation, where Sydney and Melbourne are located, states are abandoning the aim of eliminating Covid-19 and want to start reopening closed businesses and schools as early as next month and borders later this year. But the country’s more sparsely populated north and west are doubling down on “Covid Zero,” zealously defending a strategy that has allowed local residents to live maskless and with ease, though cut off from the rest of the country and the world.

“Before this pandemic, no one would have cited freedom of movement—between states and to and from overseas—as being important or significant to Australians, because it was just assumed,” says Frank Bongiorno, a professor of history at the Australian National University in Canberra. “But those rights have been drastically reduced, and that will forever change people’s conceptions of where they fit in the political order and even how they relate to authority.”

Things were very different last year. In March 2020, the country closed its international borders to noncitizens and nonresidents. It won global praise for stamping out local outbreaks with snap lockdowns. This meant Australia’s 26 million residents were able to lead largely normal lives, and deaths from the virus stayed below 1,000 even as it killed hundreds of thousands in the U.S. and Europe.

New Zealand, Singapore, Hong Kong, and most notably China embraced the same strategy. The tradeoff was international isolation. That was a burden the vast majority of Australians were happy to endure—until parts of the world once paralyzed by Covid got vaccinated and started opening up again. Now, as pandemic curbs linger, the elimination strategy is increasingly disparaged as overly cautious and unsustainable. Australia’s limits on its own citizens abroad are seen as cruel: Strict caps on international arrivals have left tens of thousands of Australians waiting to return home.

The turning point was the delta variant. One case of the highly transmissible variant broke through Australia’s defenses in June, when a limousine driver in Sydney was infected while ferrying an international flight crew between the airport and hotels used to quarantine arrivals from overseas. Now, the strain is infecting close to 2,000 people a day in the states of New South Wales and Victoria.

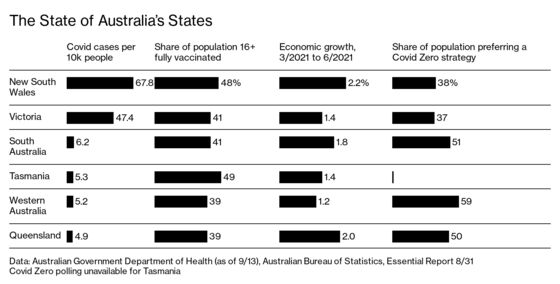

In those southeastern states, the focus has shifted away from containment and toward opening up. Although half of the nation’s population is now in lockdown, leaders in New South Wales, where Sydney is located, have promised “freedoms” such as visiting pubs, restaurants, and gyms to those who have received two mRNA or AstraZeneca Plc shots once 70% of adults are fully vaccinated. The milestone is expected to be reached next month; the current share of residents who are fully vaccinated is about 48%.

Meanwhile, 2,000 miles from Sydney, Mark McGowan, the premier of Western Australia, is adamant he doesn’t need an “exit plan,” because his state remains free of delta and free of restrictions. “Our policy to crush and kill the virus means Western Australians are living in one of the freest and most open societies in the world,” McGowan said in a statement on Sept. 9. He’s leading a group of states that want to keep the virus out for as long as they can, or until vaccination reaches extremely high levels. In Western Australia, the premier says that could be two months after 90% of adults are fully vaccinated; that figure now stands at about 39%.

Australia’s internal rift reflects the broader dilemma facing countries that have largely succeeded at blocking or stifling the pathogen. With most of the world failing to contain it and now treating it as endemic, the outliers are confronting the fact that theirs may have been a Pyrrhic victory.

The strength of these countries’ commitment to Covid Zero has varied according to how much isolation their economies could tolerate. China continues to try to stamp out all infections, while Singapore now wants to shift toward living with the virus. Australia is stuck somewhere in between, and its political system is showing the strain.

McGowan—known as “Mr. 89%” for his popularity rating while guiding the progressive Australian Labor Party to a landslide win in March’s state election—has emerged as a figure of resistance against Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who’s pressuring states to reopen their borders later this year. Even as Morrison, the leader of the Liberal Party, struggles for traction in the west, he’s desperate to sell a message of hope to pandemic-weary voters in the eastern states, especially with polls showing his coalition government trailing Labor ahead of elections that must be held by May 2022.

Yet the vaccination rate in Western Australia has been the slowest of all eight states and territories, meaning that its hard border is set to remain well into next year.

“If you’re not immediately confronted by the virus and you think your leadership is offering you a virus-free state, then your risk-benefit equations change, and people just don’t get vaccinated,” says Catherine Bennett, chair in epidemiology at Melbourne’s Deakin University. She contrasts the experience in Western Australia with what’s happening in Sydney and Melbourne, where lockdown-weary residents have overwhelmingly responded to authorities’ calls to get shots as soon as they become available.

The federal government’s tardy vaccination rollout has tarnished Morrison’s leadership credentials amid accusations by opponents that he’s botched a strong start to managing the pandemic. After telling voters as recently as March that the rollout wasn’t a race, Morrison is now urging all state and territory leaders to commit to a “national plan” of easing lockdown restrictions when 70% of all Australians aged 16 and older are fully vaccinated and allowing free domestic and international travel at 80%.

“Any state and territory that thinks that somehow they can protect themselves from Covid with the delta strain forever, that’s just absurd,” Morrison said in a television interview in August. “We need to get out of there and live with it. We can’t stay in the cave.”

Such comments don’t resonate well in parochial Western Australia. The state has a history of flirting with secession, including a 1933 referendum that showed the majority was in favor of splitting from the rest of the federation. In recent years, state leaders have been aggrieved by what they’ve perceived as the federal government siphoning off the largesse from its iron ore, natural gas, and gold exports to help bolster poorer states.

“Western Australians have a long history of seeing themselves as different, even exceptional, which comes from being not just on the periphery of the rest of the country, but of the world,” says Martin Drum, a senior lecturer in politics at the University of Notre Dame in Perth, Western Australia’s capital. “There’s often been tension between state leaders and the federal government, especially on economics, and the pandemic has exacerbated that split.”

There’s also speculation that a potential legal challenge to the state’s hard domestic border could force McGowan’s hand. The nation’s constitution states that movement of people “among the states, whether by means of internal carriage or ocean navigation, shall be absolutely free.” That could trump the rights of states, which have turned to relatively novel biosecurity legislation to justify internal borders.

One group in Western Australia is keen for McGowan to follow the eastern states’ lead in planning a quick exit from pandemic limbo: the business community, which warns there will be severe economic repercussions if McGowan tries to keep borders shut into next year. National carrier Qantas Airways Ltd. has warned that Perth may lose its status as a transit hub for flights to London.

And there are signs that isolation is adding to the costs of doing business in a city already off major shipping routes. Although demand for Western Australia’s commodities remains strong, its quarterly growth rate of 1.2% trails the national average of 1.7%. Ai Group, a lobby group representing employers, says this could be a result of labor shortages related to the hard border. There are anecdotal reports of major delays in shipping to and from the state and a shortage of new and used cars, Ai Group’s Western Australian State Manager Kristian Stratton says.

“The longer it goes on, the more difficulty we have,” says Steve Pollard, who oversees about 50 employees as chief executive of Perth-based Barclay Engineering. “There has to be recognition from the community that we’re not going to stay Covid-free and we need to end the uncertainty about when we can open back up.”

Read next: Covid Vaccine Mandates Drive Some Nurses to Leave America’s Hospitals

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.